The Economist

September 22nd 2018

51

For daily analysis and debate on Britain, visit

Economist.com/britain1

F

OREMOST in the mind of many of

those who voted to leave the European

Union on June 23rd 2016 was a desire to re-

duce immigration. Brexiteers had prom-

ised that, once shot of the

EU

and its rules

on freemovement, Britain couldmore easi-

lyclampdownonarrivals fromabroad. Yet

in the two-and-a-bit years since the refer-

endum, the government has given away

little about how it wants to alter the migra-

tion regime after Brexit.

That changed on September 18th when

theMigrationAdvisoryCommittee (

MAC

),

an official expert panel, published proba-

bly the most comprehensive-ever analysis

of migration to Britain. Its conclusions, de-

signed to inform government policy, give

the strongest hint yet of what the post-

Brexit immigration regimewill look like.

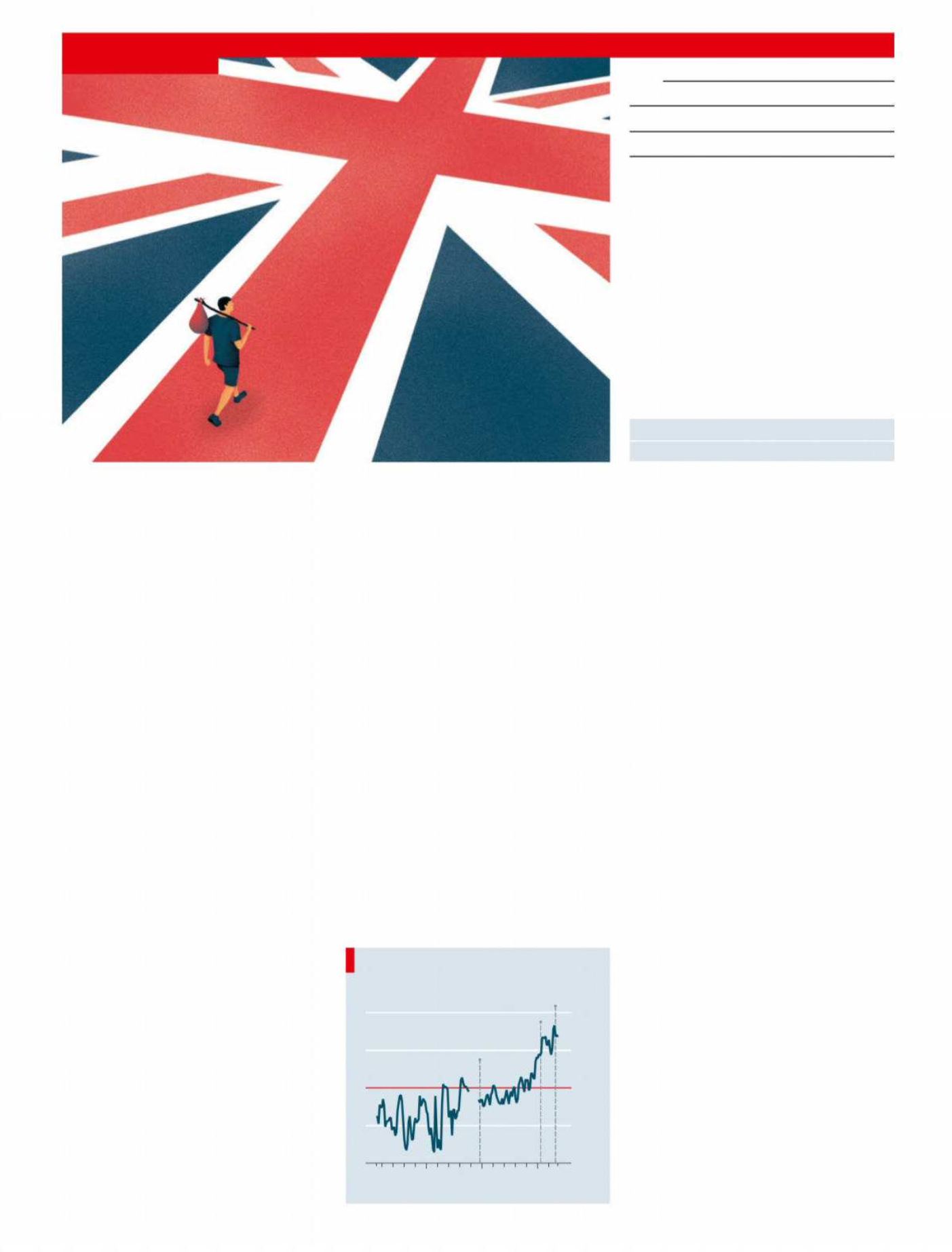

For most of Britain’s modern history

emigration has exceeded immigration (see

chart). Yet from the late 1990s immigration

rose sharply, first as a strong economy

sucked in students, workers and their fam-

ilies from around the world, and then as

the

EU

’s enlargement gave people in the

poorer east permission to work in Britain.

Annual net migration reached an all-time

peakof over 300,000 in 2015-16, shortly be-

fore the Brexit vote.

The impact of this influx on jobs, hous-

ing, the public finances and much else is

hotly contested. The 140-page

MAC

report

contains hard truths for immigration scep-

Yet the

MAC

also identifies problems.

Although migration has little overall im-

pact on wages, it pushes down the pay of

the poorest somewhat, while raising that

of the better off. Estimates in the report im-

ply that

EU

migration since 2004 has left

the wages of the poorest tenth about 3%

lower than otherwise would have been

the case, and those of the richest tenth 3%

higher. As for the public finances, the

MAC

is unconvinced that the surplus that mi-

grants produce is always directed to the

right places; it also notes that migrants’

contribution could be greater if they were

accepted on amore selective basis.

Strawberryfields for notmuch longer

It therefore suggests a shake-up. Through-

out the report the

MAC

emphasises that

different migrants have very different im-

pacts. Highly skilled workers probably

raise the productivity of British firms, by

bringing new ideas with them. Since they

earn more, they pay more tax. Lower-

skilled migrants, by contrast, do not hold

such clear benefits for existing residents.

The

MAC

worries about the consequences

of the enlargement of the

EU

in 2004, argu-

ing that since then “the scale of low-skilled

migration…has been larger than an evi-

dence-based policy would have chosen in

the absence of freemovement.”

It concludes that, from an economic

perspective, there is no reason for Britain to

discriminate in favour of

EU

citizens at the

expense of non-

EU

ones. Better, it says, to

selectmigrants on thebasis of their skills or

qualifications. The

MAC

recommends re-

moving the cap on the number of skilled

migrants who can be admitted from out-

side the

EU

, which stands at about 20,000

a year, not only because it damages the

economy but because it “makes little sense

for a migrant to be perceived as of value

tics and enthusiasts alike.

Migrants do not appear to increase

crime and seem to have no effect on the

quality of health care, the report finds. Nor

do foreign arrivals lead to noticeable rises

in joblessness among British workers—in-

deed, the unemployment rate is at a four-

decade low. Migrants also pay more in tax

than they receive in public services. Last

year those from Europe chipped in £2,300

($3,000) more than the average adult.

Without any migration, Britain’s depen-

dency ratio (the number of over-65s per

1,000 working-age folk) would jump from

285 today to 444 in 20 years’ time. With

continued net migration of 250,000 a year,

the ratiowould be 404.

Immigration policy

A neworder at the border

Britain starts drawing up a post-Brexit immigration system

Britain

Also in this section

52 Migration in Europe

53 Bagehot: May, back from the brink

Hello, goodbye

Sources: Bank of England; ONS

Britain, annual net migration, ’000

*Year to March

400

200

0

200

400

+

–

1855 1900

50

2000 18*

Brexit vote

EU accepts eight

new members

“Empire Windrush”

arrives from Caribbean