The Economist

September 22nd 2018

International 55

1

2

saster, has disputed those figures. In con-

trast, a sensible government reaction to

Florence probably helped limit damage

and loss of life. Mandatory evacuation or-

derswere issued three days before landfall.

NewOrleans only got such an order on the

eve ofKatrina’s arrival.

That Florence was not a chart-topping

storm is small comfort to the North Caro-

linianswhose homes and businesseswere

destroyed. Local economies could take

years to recover. Some homeowners will

be compensated by the national flood-in-

surance programme, which is subsidised

by the government, in effect paying people

to live in areas at high riskofflooding. Even

so, the Federal Emergency Management

Agency estimates that 40% of small busi-

nesses never reopen after a natural disas-

ter. The state’s livestock industry has al-

ready taken a beating. The state agriculture

department said that Florence had killed

3.4m chickens and drowned 5,500 pigs.

Such casualties are expected to rise.

There’s no sun up in the sky

If storms can wreak such havoc in the

world’s richest country, their impact in

poor Asia-Pacific countries is even more

far-reaching. Every year, the Asia-Pacific re-

gion is battered bymore and bigger storms

than reach America. There, the approach

has been to move people away from the

coast where possible. After Bangladesh

found itself in 1970 in the path of cyclone

Bhola, which killed between 300,000 and

500,000 people, making it the deadliest

tropical cyclone on record, it began build-

ing a large network of raised shelters. Still,

some people would refuse to use them. So

now they accommodate livestock as well

as people; have separate facilities forwom-

en; and are accessible to the disabled. But,

according to Saleemul Huq, who directs

the International Centre for Climate

Change andDevelopment, a research insti-

tute in Dhaka, the Bangladeshi system’s

biggest success has been its education pro-

gramme, whichhas taught childrenhowto

respond to earlywarnings and take shelter.

The Philippines, too, has grim experi-

ence of storms. Haiyan, one of the stron-

gest tropical cyclones yet recorded, which

struck in 2013, remains a fresh memory. It

pummelled the central part of the Philip-

pines and crossed the country, killing 6,300

people and leaving1,062missing, by the of-

ficial count. In comparison, the govern-

ment’s handling of Typhoon Mangkhut is

counted a success. After it passed, Harry

Roque, a spokesman for President Rodrigo

Duterte, said his bosswas “very, very satis-

fied” with the effort.

Yet by September 19th the death toll

stoodat 81people and 70were stillmissing.

The number will probably rise. Rescue

workers are still findingvictims of themost

deadly landslide, which buried a commu-

nity of illegal miners digging for gold in a

worked-out mine in the Cordillera moun-

tains, in the north of Luzon, the main is-

land. On September 15th, the day when

Mangkhut hit Luzon, the National Disaster

Risk Reduction and Management Council

(

NDRRMC

) reported 194,368 people had

taken refuge in shelters (mainly schools). It

estimated the cost of the damage to agri-

culture at 14.3bn pesos ($264m). Later the

NDRRMC

estimated that about 1.1mpeople

had been affected by the storm.

Haiyan affected far more people, but in

some respects Mangkhut, though it passed

through only the north of Luzon, was big-

ger. Its bands of rain-bearing cloud swirled

around an area 900km in diameter. As it

approached Luzon, its winds sustained

speeds of up to 205kph (127mph) near the

centre, with gusts of up to 255kph.

One lesson learnt from earlier disasters

was the need for earlier andmore emphat-

ic advice to people to seek refuge. The gov-

ernment’s weather-forecasting service,

called

PAGASA

, was tracking Mangkhut

well before it reached Luzon. It warned of

strong winds and heavy rain that would

cause highwaves at sea, stormsurges up to

six metres in height along the coast, and

flooding and landslides inland.

PAGASA

has been tracking roughly 20

storms a year since its founding in1972, and

this time its forecasts were accurate. They

were translated into warnings spread on

radio and television, by text message and

over the internet. Radio is the most widely

used mass medium, and only the poorest

Filipinos arewithout mobile phones.

Mangkhut’s winds blew down flimsy

buildings, tore the roofs off sturdier ones

and felled trees. But, like Florence, it

wreaked most of its destruction through

rain, which caused landslides and flash

floods, inundating fields and ruining the

crops in them, making roads impassable

and cutting off electricity supplies. The

storm halted all normal economic life.

Schools were closed, to keep the pupils

safe and to be used as public shelters; busi-

nesses were shuttered; ferry sailings and

international and domestic flights were

cancelled. Mobile-phone networks were

generally resilient, however.

The Philippines has a hierarchy of di-

saster-risk reduction, and management

councils at every level of government. The

system worked quite well this time. But it

suffers from a malaise that afflicts the en-

tire political structure. Politicians at the

centre can saywhat they like, but local pol-

iticians do what they like. It also faces a

more universal problem: that some disas-

ter victims think they know best or, as in

Bangladesh, are reluctant to abandon their

property, such as livestock, to take shelter.

The freelance miners in the Cordillera had

that attitude. Most of those who died dur-

ing Typhoon Haiyan were killed by storm

surges in the eastern city of Tacloban, hav-

ing been directed to take refuge in coastal

shelters. Local lore had it that if a typhoon

was coming, safetywas in the high ground.

Haiyan also shows the importance of

official competence. The interior minister

at the time, Mar Roxas (later one of the

presidential candidates defeated by Mr

Duterte), directed the response from Taclo-

ban, but omitted to take a satellite phone.

When the storm made mobile-phone net-

works inoperable and prevented him leav-

ing Tacloban, he was unable to respond to

looting. Before Mangkhut struck, Mr Du-

terte called for the wider use of satellite

phones by the authorities.

Mangkhut was not through when it left

the Philippines. It terrorised Hong Kong

(see box on next page) and Macau, where

high winds and flooding left some 20,000

households without power—and, unprec-

edentedly, all 42 casinos shut for 33 hours.

The city appeared better prepared than it

was before Hato, last year’s largest ty-

phoon, inwhich ten people died. This time

no liveswere lost.

The same dayMangkhut made landfall

in Guangdong, China’s most populous

province, flooding coastal and riverside

neighbourhoods, and toppling thousands

of trees. China’s state weather bureau said

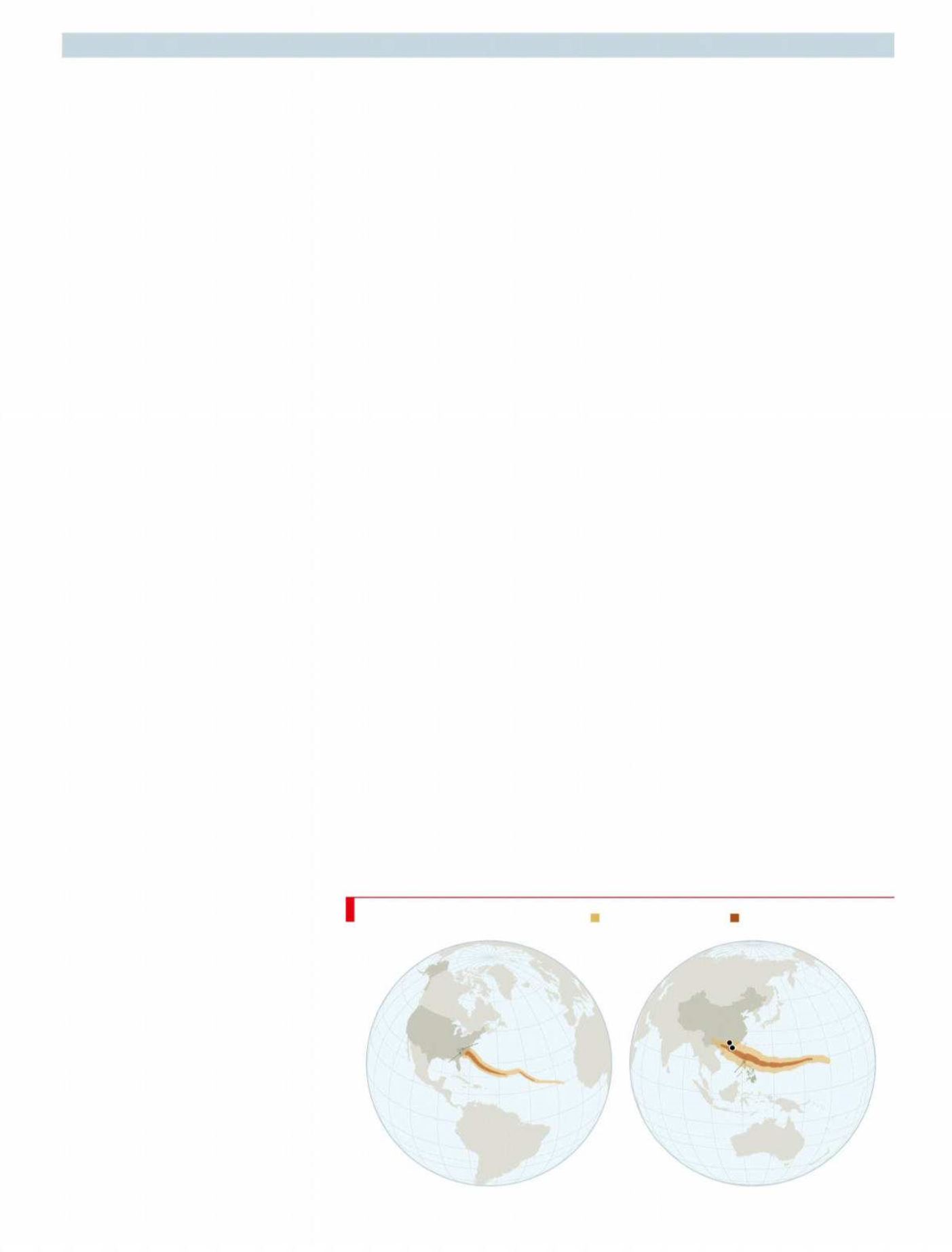

A T L A N T I C

O C E A N

UNITED

STATES

NORTH CAROLINA

SOUTH CAROLINA

P A C I F I C

O C E A N

PHILIPPINES

Hong Kong

Guangzhou

CHINA

LUZON

Wind speeds*

Tropical storm

(63-118 km/h)

Hurricane/typhoon

(>118 km/h)

Trails of destruction

Hurricane

Florence

Sources: NOAA; Global Disaster Alert and Coordination System

*Sustained surface wind speeds

Typhoon

Mangkhut