The Economist

September 22nd 2018

Britain 53

T

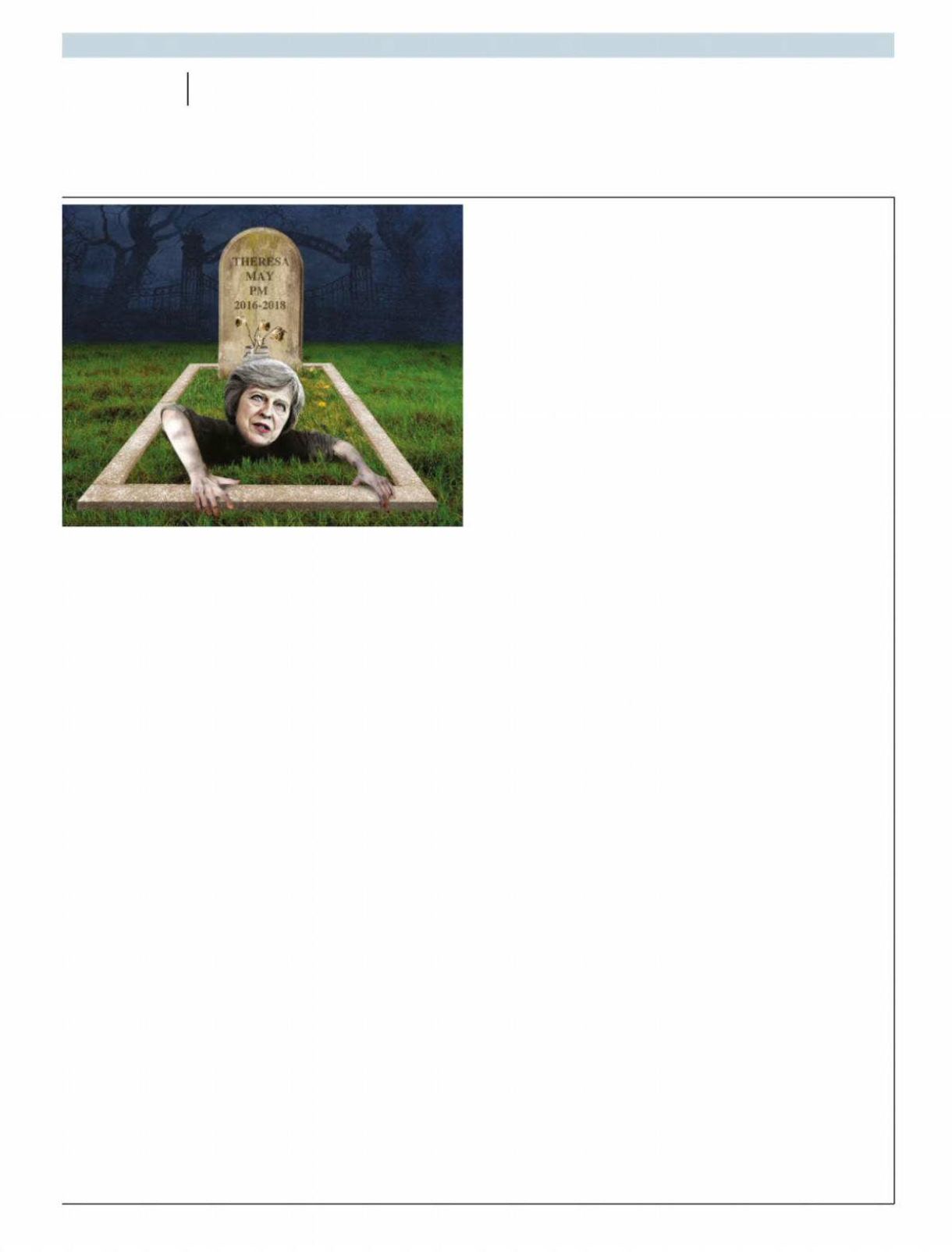

HERESAMAY is about to enter themost challengingperiod of

a prime ministership that has already been extraordinarily

testing. She has to forge a deal with a EuropeanUnion that senses

her weakness. She has to confront a Conservative Party confer-

ence that smells betrayal. Trickiest of all, she has to get her Brexit

deal through a fractious House of Commons. And she has to do

all this knowing that the price of failure couldbe political turmoil,

economic catastrophe and a place in the history books alongside

Britain’sworst primeministers.

What are the chances of her succeeding? It is impossible to

make firm predictions in such fractious circumstances. Yet there

are signs that politics is at last moving in the prime minister’s di-

rection. Mrs May has often been cursed by dismal luck. Who can

forget her excruciating performance at last year’s party confer-

ence, when she was seized by a coughing fit and the backdrop of

the stage collapsed behind her? But just when she needs it, her

luck has changed. The

EU

is sounding friendlier as the Brexit ne-

gotiations near their conclusion. A political meltdown in Britain

would have severe repercussions on both sides of the Channel.

And her fractious party is showing signs that it might fall in line.

Mrs May is lucky in her internal opposition. The leader of the

campaign to unseat her, Boris Johnson, is widely regarded by his

fellowConservative

MP

s as a rogue and a risk. The fact that, at the

same time, he is so popularwith the Tory grassroots provides her

with her most powerful whipping device: support me or you

might end up with this disaster-in-waiting. The Brexiteer faction

as a whole contains a large number of what might politely be

called eccentrics. The credibility, such as it is, of the European Re-

search Group (

ERG

), a caucus of hardline Brexiteer

MP

s, recently

tooka divewhen it failed to produce its own Brexit plan. MrsMay

has also been lucky in a changing of the guard at the

Daily Mail

,

Britain’s most important tabloid newspaper, where Paul Dacre, a

fierce Brexiteer, has been replaced byGeordie Greig, an ardent re-

mainer. The

wastedno time inmaking funof the fact that the

ERG

’s abortive Brexit document included plans to equip Britain

with a nuclear-missile shield.

Mrs May is also fortunate in her opposition across the parlia-

mentary aisle. The Tory party is far more worried about Jeremy

Corbyn than it was when he won Labour’s leadership election

three years ago. Not only has he failed to soften his far-left posi-

tion on domestic policy, he has also undermined the govern-

ment’s position on the murder of two British citizens by Russian

intelligence operatives. All but the most fanatical Brexiteers

would fall in line if they thought that failing to do so might hand

Britain over to a man who has spent his life protesting against

“Western imperialism” and campaigning for more trade-union

power. Mr Corbyn has also failed to produce a plausible Brexit

policy of his own. Six months before Britain leaves the

EU

, La-

bour’s policy consists of little more than having its cake and eat-

ing it (somehow maintaining the benefits of the single market

while also forging its own rules) and meaningless platitudes (“a

pro-employment Brexit”).

This autumnmayplay toMrsMay’s political strengths. Britain

has become so familiarwithherweaknesses over the past year or

so—her lack of human empathy, her habit of repeating the same

monotonous phrase (“strong and stable”, “nothing has

changed”), her combination of stubbornness and weakness—

that it is easy to forget that she has formidable qualities. The first is

her sheer relentlessness. Mrs May lacks the political gifts of natu-

ral politicians such as David Cameron and Tony Blair. She suffers

from type one diabetes, which means she has to inject herself

with insulin several times a day. But she has made it to the top re-

gardless. Her almost freakish focus on getting the job donewas il-

lustrated during a press conference in a basement in Ramsgate,

Kent, in the run-up to the general election of 2015. The lights blew

out, plunging the room into darkness, but the Maybot continued

regardless, taking questions on arcane bits of policy.

Her second strength is her sense of duty. Mrs May is an anti-

populist politician who found herself prime minister at a popu-

list moment. She is a grammar-school girl who made it into the

cabinet by dint of hard work and common sense. By an odd

chance shewas put into the top job by a referendum that was dri-

ven by populist rage against the establishment. The dutiful Mrs

May set herself three tasks: obeying the “will of the people”, as ex-

pressed in the referendum; leaving the

EU

without damagingBrit-

ain’s economy; and doing all thiswithout splitting her party.

Against the odds

She faces an excruciating task. For her to succeed, a lot of things

have to go right. For her to fail, just one has to gowrong. She has to

produce a deal that satisfies both Brussels and the bulk of the

Brexiteers. She has to forge amajorityby keepingher party in line

orwinningover enoughwavering Labour

MP

s tomake up for the

Tory rebels. There is every chance that her government will be

consumed by paralysis—that her compromise doesn’t get

through and that she has nothing to replace it. This could produce

any number of outcomes: a putsch in the Conservative Party,

withMrsMay replaced by a rival; a general election, withMrCor-

byn likely to get into Downing Street; or a second referendum,

which could evenmean Brexit was reversed.

David Cameron and his acolytes always looked down onMrs

May as a dutiful dullardwho got a second-class degree in geogra-

phy from St Hilda’s and then went on to rise without a trace. But

dutiful dullards frequently end up better regarded than talented

chancers. Mrs May is trying her best to clear up the terrible mess

that the Bullingdon boy left for her. And if her luckholds, and she

succeeds in pushing a workable compromise through Parlia-

ment, she will deserve thanks as well as admiration. There is

honour, if not glory, inmaking the best of a bad job.

7

Back from the brink

At last, thingsmaybe turning in the primeminister’s favour

Bagehot