The Economist

September 22nd 2018

57

For daily coverage of business, visit

Economist.com/business-finance1

A

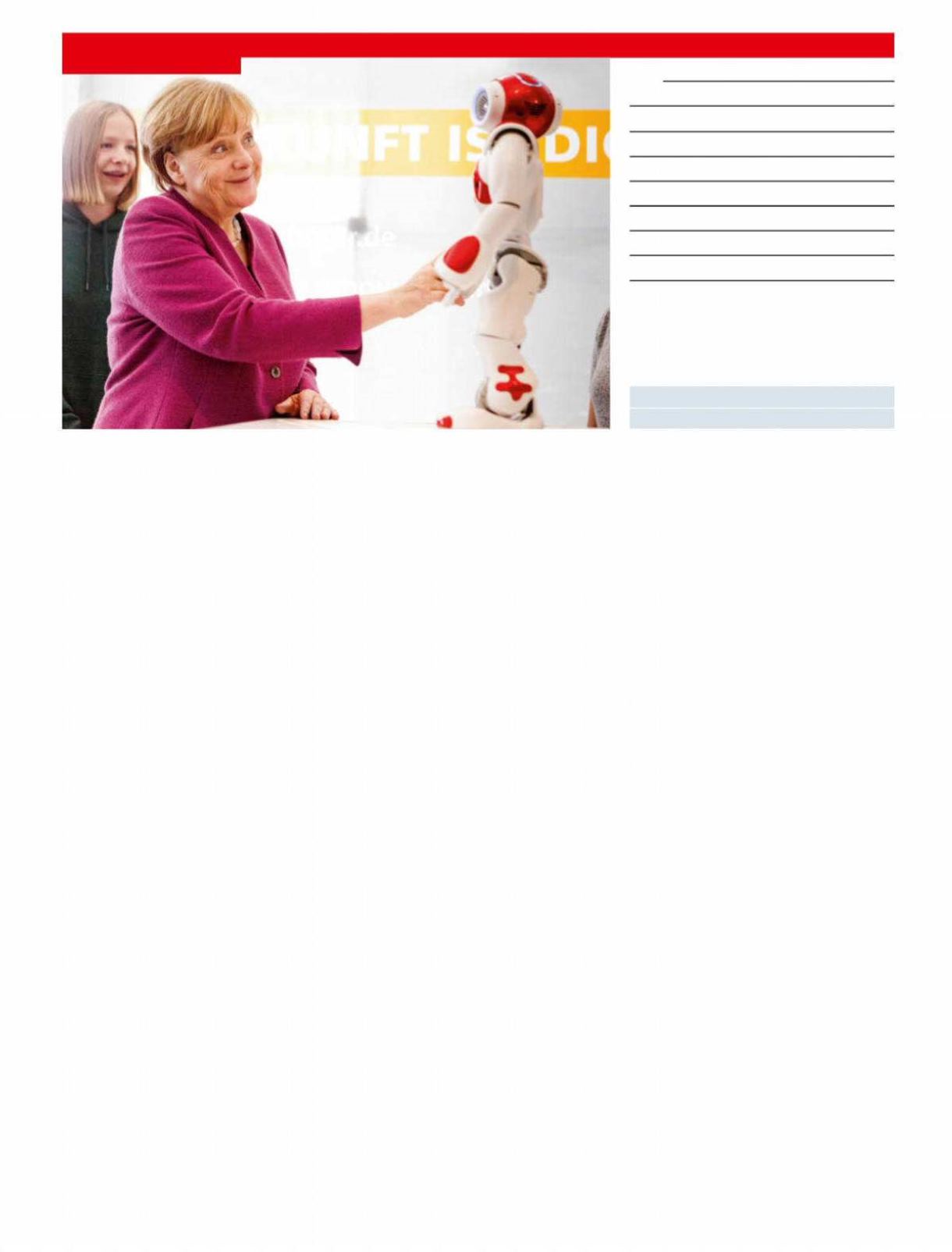

NGELA MERKEL, Germany’s chancel-

lor, has a reputation for beingdour. But

if she wants to, she can be quite funny.

When asked at a recent conference organ-

ised by

Ada

, a new quarterly publication

for technophiles, whether robots should

have rights, she dead-panned: “What do

you mean? The right to electric power? Or

to regularmaintenance?”

The interviewwas also striking for adif-

ferent reason. Mrs Merkel showed herself

preoccupied by artificial intelligence (

AI

)

and its geopolitics. “In the

US

, control over

personal data is privatised to a large extent.

In China the opposite is true: the state has

mounted a takeover,” she said, adding that

it is between these two poles that Europe

will have to find its place.

Such reflections are part of awider real-

isation in Europe: that

AI

could be as im-

portant to its future as other foundational

technologies, like electricity or the steam

engine. Some countries, including Finland

and France, have already come upwith na-

tional

AI

strategies, and Germany is work-

ing on one. Once it is finished later this

year, the European Union will condense

these efforts into a co-ordinatedplanon

AI

.

Unsurprisingly, it is all highly Eurocratic:

dozens ofcommittees andother bodies are

involved. But the question raised by Mrs

Merkel is as vital for Europe as the ones

about Brexit or immigration: can it secure a

sizeable presence in between the

AI

super-

powers ofAmerica and China?

People in Silicon Valley are sceptical. “It

run on data alone but needs other

AI

tech-

niques, such as machine reasoning, which

is done by algorithms that are coded rather

than trained—an area in which Europe has

some strength. Germany has as many in-

ternational patents for autonomous vehi-

cles as America and China combined, and

not only because it has a big car industry.

Nor are ever-larger pools of data and

ever-more powerful chips the only way to

go. More researchers are looking into what

can be done with “small data”—ie, using

fewer data to train algorithms—particular-

ly in manufacturing and the internet of

things. This is where Europe, home to

many industrial firms, could have an ad-

vantage. “As

AI

gets more complex, Europe

will have opportunities,” predicts Virginia

DignumofUmea University in Sweden.

Old Europe andwiserAI

Europe’s biggest opportunity, however,

may be political and regulatory rather

than technical. As Mrs Merkel noted,

America andChina represent two fairly ex-

trememodels on

AI

—which leaves room in

the middle. “Europe could become the

leader in

AI

governance,” says Kate Craw-

ford, co-founder of the

AI

Now Institute, a

research centre at NewYorkUniversity. Eu-

rope could pioneer rules to limit potential

harm from

AI

systems when, for instance,

algorithms are biased or run out of control.

Many people hope that Europewill set glo-

bal standards in

AI

, as it is doing with its

new privacy law, the General Data Protec-

tion Regulation, whose principles have

beenwidely copied elsewhere.

Other types of regulation offer a similar

opening. Both America and China are cen-

tralised data economies, in which this re-

source is controlled by a few firms. Europe

has a shot at developing a more decentral-

ised alternative, in which data are traded

or shared between firms. That could in-

volve defining access rights to data (the

will screw this up, just as it has done with

cloud computing,” says JackClarkofOpen

-

AI

, a company that aims to promote hu-

man-friendly

AI

. Hardly anyone in the Bay

Area can imagine Europe becoming a force

in machine learning, the

AI

technique that

has seenmost progress in recent years. It in-

volves feeding reams of data (pictures of

faces, for instance) through algorithms so

they learn to interpret other data (in this ex-

ample, to recognise people in videos).

That scepticism is not only because of

self-inflicted weaknesses such as Europe’s

“tendency to favour incumbent business

over disruptive newcomers”, in the words

of Greg Allen of the Centre for a New

American Security, a think-tank. The re-

gion also has a structural disadvantage: a

lack of scale. Benefiting from huge, homo-

geneous home markets, America’s and

China’s tech giants have a surfeit of the

most vital resource for

AI

: data.

This advantage creates others. Having

more datameans that firms can offer better

services, which attractmore users and gen-

eratemore profits—money that canbe used

to hire more data scientists. And having a

lot of data creates demand for more com-

puting power and faster processors. All the

big cloud-computing providers, including

Amazon and Microsoft, are developing

their own specialised

AI

chips, an area

where Europe is also behind.

Yet look beyond machine learning and

consumer services, and the picture for Eu-

rope is less dire. A self-driving car cannot

Artificial intelligence and Europe

Big data, small politics

BERLIN AND BRUSSELS

The EuropeanUnion is gearing up in an attempt to challenge theAI superpowers,

America andChina. Is it too late?

Business

Also in this section

58 Bartleby: Soaring

staff turnover

60 Marc Benioff and Time

60 American railways

61 Tesla’s latest troubles

61 Indian idol manufacturing

62 Doing business in North Korea

63 Schumpeter: AIA and Prudential