The Economist

September 22nd 2018

Business 61

1

2

A

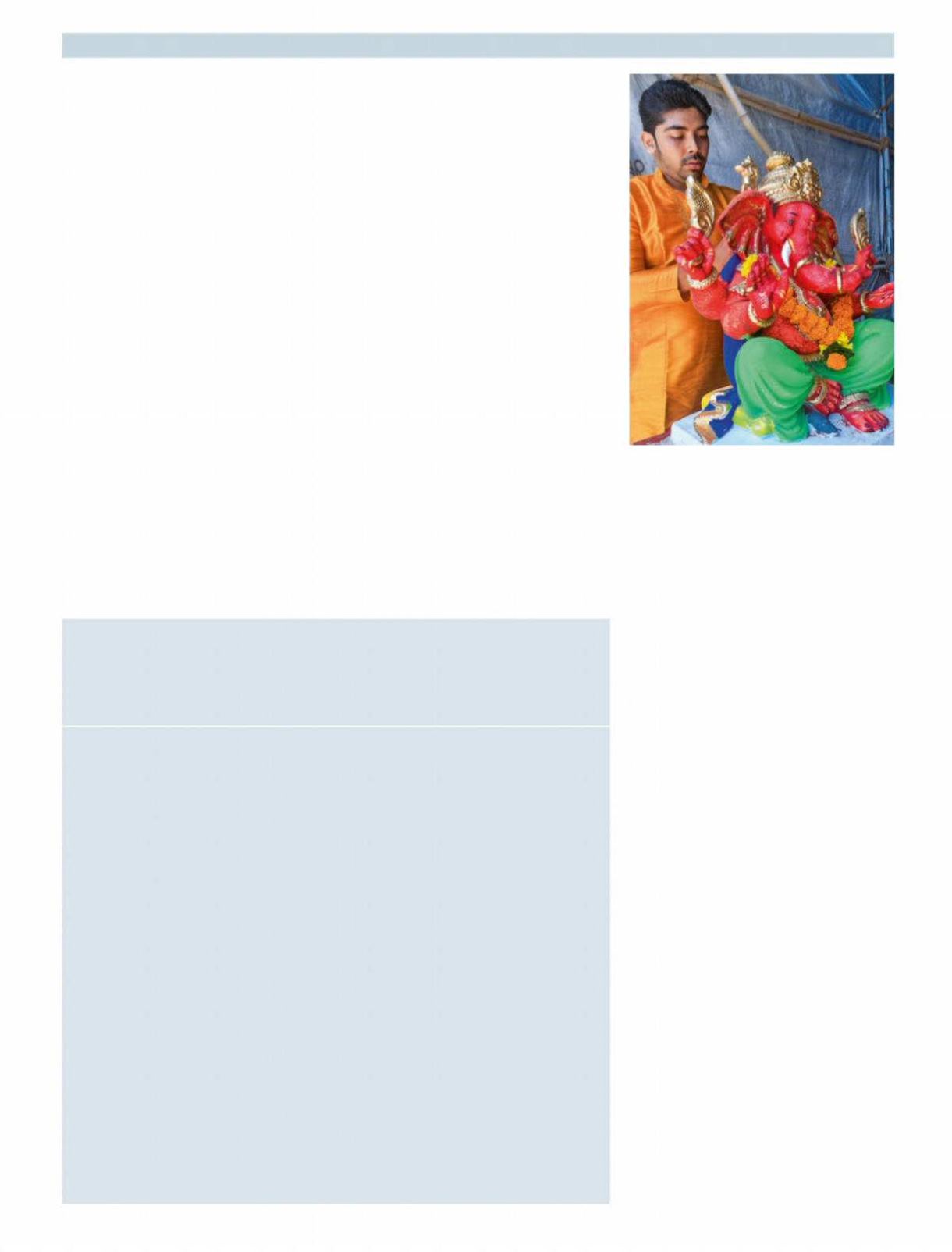

TTHE gate of an oldwarehouse in Low-

er Parel, in what was Mumbai’s mill

district, a cannon fires a burst of confetti to

celebrate the exit of a god. The Hindu deity

in question is the smiling, elephant-head-

ed Ganesha, who is thought to bring good

luck and remove obstacles in people’s

lives. This Ganesha is 20 feet tall and

mounted on a blue cobra throne; he is

pushedby a teamofyoungmen. Inside the

gates, amid a fog of spray-paint, workers

are putting the final touches to perhaps 50

more Ganeshas ofonly slightlymoremod-

est size. One rides a plaster tiger the size of

a large horse, suspended inmid-leap.

Ganesh Chaturthi, the festival celebrat-

ing Ganesha, which started on September

13th and lasts 11 days, is one of the year’s

biggest events in Mumbai. Modest Ga-

nesha statues are brought into family

homes and worshipped; bigger, gaudier

ones aremounted inpublic spaces by com-

munity groups and firms. At the festival’s

end, hundreds of thousands of idols are

ceremonially carried into bodies of water

and left to disintegrate. An entire industry

exists to provide Maharashtrians (resi-

dents of the state of which Mumbai is the

capital) with suitable gods. It offers insight

into the chaotic, informal and fiercely com-

petitive nature ofmuch Indian business.

The warehouse in Parel is usually used

to host weddings and other events; but

from around June until mid-September it

becomes a workshop. Arms, legs, torsos

and heads made from plaster of Paris are

brought in from factories in the country-

side. In Mumbai they are bolted together

rather like giant Airfix kits.

The workers, like the workspace, are

temporary. Every monsoon season, hun-

dreds come fromother parts of India; most

are farmers the rest of the year. “There is no

work in the rainy season, so we come

here,” says the auspiciously named Avi-

nashGaneshKar, a 22-year-oldwhomakes

500 rupees ($7) a day painting gods. While

in Mumbai, workers sleep and eat as well

aswork in thewarehouse.

The Ganesha industry is also almost

entirely cash-based, with little credit in-

volved. Many taxes go unpaid. And

though permits are needed for almost

everything—fromelectricity to the services

of the fire brigade—theyare easilyobtained

by Lord Ganesha’s munificence, meaning

possibly a bribe or two.

At the same time, the entrepreneurs

building gods are admirably competitive,

innovative and sensitive to local tastes.

Thesedays, smallerGanesha statuesareof-

ten made more cheaply in China and

shipped in. But the bigger ones are special-

ist products. A human-size Ganesha may

start from 120,000 rupees. A 20-foot one

costs far more. For that, customers expect a

Indian manufacturing

The idolatry

industry

MUMBAI

What Ganesha statues reveal about

Indian business

Is it green enough?

tors, a trade group. Congress has under-

funded it and limits its ability to raise

privatemoney for newprojects.

Matt Coogan, an American rail expert,

warns that Brightline could struggle to get

space for its trains on future projects where

it needs to use existing lines. Other track

owners want to give their own freight

trains priority and balk at investing the

money needed to run passenger trains at

faster speeds. Brightline could build new

tracks, as it plans tobetween

LA

and LasVe-

gas. But this is likely to cost billions of dol-

lars for each of the 10-15 lines it wants to

build. Some analysts say it would need to

issuemore equity, perhaps in an

IPO

.

Another threat is competition from

publicly funded high-speed rail projects.

But there is opposition to their cost ($77bn

and rising for

LA

to San Francisco, a section

of which is already under construction);

Brightline thinks it can build new lines

more cheaply and quickly than any public

initiative. Nonetheless, to get his sums to

add up, Mr Edens admits that public per-

ceptions of train travel as drabwill need to

change. They already have in Europe, he

notes. On a recent visit to St Pancras in Lon-

don, an insalubrious area before redevel-

opment a decade ago, he saw a couple get-

ting married at the station. “There’s no

reasonwhywe can’t get there too.”

7

Tesla’s latest troubles

The enemywithin

“W

E ARE about to have themost

amazing quarter in our history.”

So declared ElonMusk in an email on

September 7th to employees of Tesla, his

electric-vehicle (

EV

) firm. This cheery

promise came on the heels of self-inflict-

ed blows, most obviouslywhenMrMusk

tweeted carelessly that he had “funding

secured” to take the company private,

prompting a spike in its share price.

Trouble is looming on several fronts.

On September18th Tesla confirmed that

America’s Department of Justice (

D

o

J

)

has asked for documents relating to the

problematic tweet. MrMusk later jetti-

soned the plan to go private (while still

maintaining that the funding to do so had

been available). The

D

o

J

’s interest comes

on top of a civil investigation by the

Securities and Exchange Commission

into the tweet and into the company’s

claims about sales andmanufacturing

targets. But Urska Velikonja ofGeorge-

town LawSchool says the

D

o

J

’s involve-

ment is a significant escalation because it

raises the spectre of criminal charges.

Even ifMrMusk is found innocent, a

lengthy probe couldmake it harder for

Tesla to raisemore capital.

A spate of lawsuits is another head-

ache. AndrewLeft ofCitron Research is

suing Tesla, claiming that MrMusk re-

leased false information about going

private in order to “burn” short-sellers

who had bet that shareswould fall. Class-

action lawsuits claimingmassive dam-

ages to shareholders resulting from the

troublesome tweet have also been filed.

Competition is hotting up, too. Saudi

Arabia’s sovereign-wealth fund, which

holds a $2bn stake in Tesla, thisweek

announced it would invest over $1bn in

LucidMotors, a Californian

EV

rival. Nio,

a promisingChinese

EV

startup, raised

$1bn thismonth through a flotation on

the NewYorkStockExchange. And on

September17th Audi unveiled the e-tron,

an electric sports-utility vehicle.

If Tesla is to survive the onslaught, it

must overcome itsmanufacturing snags

and scale up production fast. MrMusk

tweeted thisweek that his firmhas made

progress, going from “production hell” to

“delivery logistics hell”. He vows it will

become “sustainably profitable” this

quarter. That would be amazing indeed.

Regulatory scrutiny, lawsuits and rising competition add to ElonMusk’swoes