The Economist

September 22nd 2018

Finance and economics 67

1

2

the EuropeanUnion’s trade commissioner,

unveiled a “concept paper” outlining re-

forms that could plug some of the gaps in

the

WTO

’s rules, as well as ways to reform

dispute settlement. But it is far from clear

whether either Mr Trump or the Chinese

government will take the bait.

And without the multilateral rules-

based system to contain the conflict, the

trade war between China and America

could get much bloodier. In his announce-

ment on September 17th Mr Trump threat-

ened to hit another $267bn-worth of Chi-

nese imports ifChina retaliated against his

latest tranche of tariffs. For their part, the

Chinese show little sign of backing down,

and have promised to use fiscal policy to

soften any domestic blow.

Although they are running out of

American exports to target, they have oth-

er ways to fight. On September 17th, for ex-

ample, reports emerged of a Chinese offi-

cial musing about China repeating its trick

of imposing export restrictions on rawma-

terials that American manufacturers de-

pend on. The next day, Craig Allen, chair-

man of the

US

-China Business Council,

warned that the

WTO

had made clear its

opinion that such restrictions were illegal.

But why, when America is acting outside

the rule book, should others stick to it?

7

M

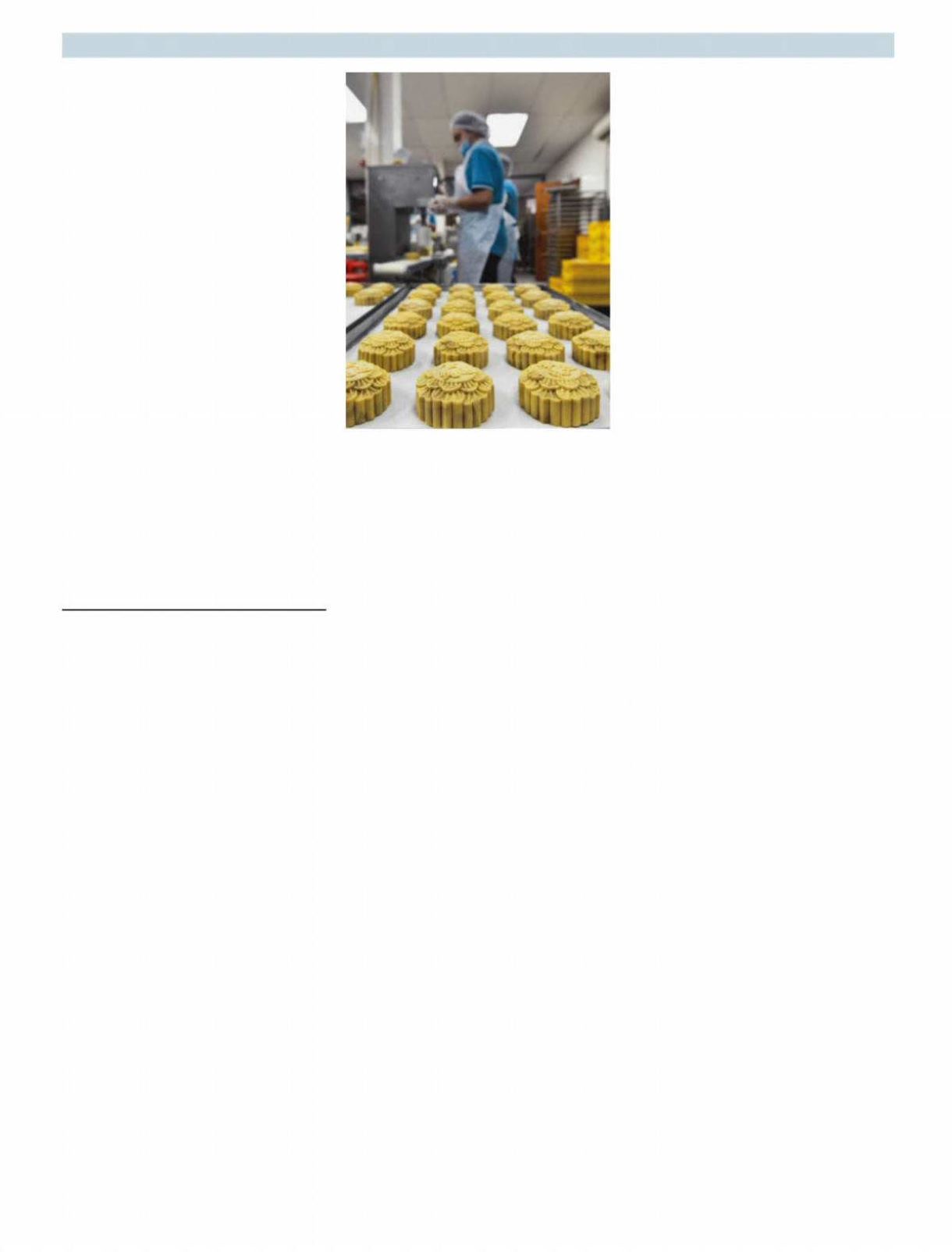

OONCAKES are among the most di-

visive treats. For some the chewy

pastries are delicacies on which to gorge

for the Mid-Autumn Festival, a Chinese

holiday that falls this year on September

24th. For others they are dry, dense and full

of calories. But for economists they are

something else entirely: an indicator of im-

portant trends in consumption, innova-

tion, corruption and grey-market trading.

Mooncakes play this role because of

their status as gifts. Ahead of the mid-au-

tumn holiday, companies give them to em-

ployees; business contacts exchange them.

Consumption of mooncakes is thus less a

reflection of whether people enjoy the

pastries, likened by some to edible hockey

pucks, andmore ameasure of the health of

the economy. So it is heartening to know

that, amid rising trade tensionswithAmer-

ica, the Chinese bakery association has

forecast that sales of mooncakes will rise

by a solid 5-10% this year.

Some observers fret that Chinese con-

sumers, burdened by rising debt, have

started opting for cheaper goods. But con-

sumers still plump for more expensive va-

rieties ofmooncakes rather than the classic

nut-and-egg-yolk fillings. Shangri-La, a

five-star hotel chain, has won fans with its

blueberry-cheese mooncake (dismissed

by traditionalists as cheesecake). Judging

by long queues at Häagen-Dazs stores,

mooncake-shaped ice-cream sandwiches

are also booming. At least 30 listed food

companies, more than ever before, are vy-

ing for a bite of the $2bnmooncakemarket

this year.

Mooncakes have long given off a whiff

of corruption. Businesses seeking favours

fromofficials send lavishlywrappedboxes

of them. When Xi Jinping, China’s power-

ful president, intensified his anti-graft cam-

paign in 2013, themooncakemarket shrank

bymore than 20%. Arebound over the past

three years has naturally fuelled talk of a

rebound in bribery, too. The government

has denied this. Yet it is clearly worried.

The front page of the newspaper published

by the Communist Party’s anti-graft agen-

cy warned on September 17th that al-

though mooncakes are small, they can

point tomuch bigger problems.

Perhaps the tastiest morsel frommoon-

cakes is what they reveal about China’s

grey economy. Scalpers hawking moon-

cake gift coupons have taken to Shanghai’s

streets in recent days, as theydo every year,

standing outside busy subway stations

and popular bakeries. Most economic

studies describe scalping as a phenome-

non that arises when scarce tickets to

sporting events or concerts are resold at a

hefty markup. Yet there is no shortage of

mooncakes inChina. The problem is ineffi-

cient allocation: toomany coupons are giv-

en to peoplewho do not like them. China’s

economy has plenty of inefficiencies,

whether in the form of state-owned com-

panies or gift-giving customs. But it some-

times also has solutions.

7

Mooncake studies

Reading the

crumbs

SHANGHAI

What a controversial pastry says about

China’s economy

Gift or graft?

“T

HE bank has clearly failed to live up

to its responsibility,” saidOle Ander-

sen, chairman ofDanske Bank, on Septem-

ber 19th. Well, indeed. The findings of an

inquiry into the laundering of money,

much of it from Russia, through Danske’s

Estonian branch are sobering. The euro

amount rinsed through the branch’s books

runs to12 digits andDanskemissed chance

after chance to stop the sluice. To no one’s

surprise its chief executive, Thomas Bor-

gen, has resigned.

Denmark’s biggest bank had already

admitted doing too little to prevent the

abuse of its branch between 2007, when it

bought Finland’s Sampo Bank, the unit’s

owner, and 2015. An 87-page report by

Bruun & Hjejle, a law firm, both tries to

quantify the suspicious activity and traces

how Danske’s anti-laundering procedures

went so catastrophicallywrong.

The main conduit was the branch’s

“non-resident portfolio”, comprising

about 10,000 accounts, of which 3,000-

4,000 were open at any one time. The

branch also housed another 5,000 non-

residents’ accounts. Starting with the fishi-

est, the investigators have examined 6,200

accounts and deem “the vast majority” to

be suspicious. By contrast, the branch had

reported only 760 clients to the Financial

Intelligence Unit, the Estonian police divi-

sion dealing with financial crime. The in-

vestigators have identified 177 customers—

mostlypartnerships registered inBritain or

well-known tax havens—potentially in-

volved in the “Russian Laundromat”, a

vast fraud exposed by the Organised

Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, a

group of investigative journalists.

Mere suspicion, of course, proves noth-

ing. As the investigators did not sift the

9.5m transactions on the 15,000 accounts,

they cannot sayhowmuchwas laundered.

But by any reasonable guess, the sum is

staggering: €200bn ($234bn at current ex-

change rates), mostly in euros and dollars,

flowed through the accounts, 23%of it from

Russia. “It is expected that a large part of

the payments were suspicious,” the report

drily concludes.

Chances to clean up went begging al-

most from the day Danske bought Sampo.

In 2007 the Estonian authorities found

flaws in Sampo’s procedures, and the Rus-

sian central bank told Danish supervisors

that non-resident customers “perma-

nently participate” in transactions intend-

ed to avoid taxes and customs payments,

Money-laundering

Questionable

shape

Denmark’s biggest bankreports on its

Estonian shambles