68 Finance and economics

The Economist

September 22nd 2018

2

M

ARIO DRAGHI, boss of the Euro-

pean Central Bank (

ECB

), is a pol-

ished speaker, clear and direct. Yet there

was amoment after the bank’smonetary-

policy meeting on September 13th when

he was uncharacteristically vague. Asked

how the

ECB

might recycle the proceeds

from maturing bonds once it ends its

bond-buying programme, he said the is-

sue had not come up. “We haven’t even

discussedwhenwe’re going to discuss it.”

Perhaps at the meeting in November. Or

December. It will be soon, anyway.

Much ofwhat central banks do is now

telegraphed well in advance. Despite the

occasional absurdities involved in giving

fine-grained “forward guidance”, the Fed-

eral Reserve, the

ECB

and others have

trained investors to knowwhen to expect

an increase in interest rates. Indeed, cen-

tral-bank watching is no longer just con-

cerned with clues about the timing of in-

terest-rate changes or plans for bond

purchases or sales. It has reached a more

elevated plane, where statements by cen-

tral bankers are parsed for signs of what

theymight soon sayaboutwhat theymay

eventually do.

It is a surprise, then, that forward guid-

ance has had consequences for currency

markets that have gone almost unnoticed.

In China, policies can change without

much in the way of prior signalling. So

when the yuan moves, it carries rare

news—about currency demand, about

China and by extension about the world

economy. Increasingly it is the yuan that

shapes the foreign-exchangemarket.

It is still a longway frombeing a global

currency. The yuan has not made great

strides as a trading or reserve currency.

The dollar is still king. Of the $5trn traded

in currencymarkets each day, the dollar is

on one side of the exchange in almost

nine out of ten transactions. Crude oil is

priced in dollars. The bonds issued by

countries and by globalised firms are likely

to be in dollars if they are not in their home

currency. And the dollar accounts for two-

thirds of foreign-exchange reserves. The

yuan barely registers.

China looms large as an importer and

exporter. It is the largest trading partner for

almost every country on the planet. But

the trade it dominates is priced, invoiced

and settled mostly in the currency of

America. Indeed, suchwas the importance

of exports to China’s economy that, until

quite recently, the yuan’s valuewas pegged

tightly to the dollar.

Offthe peg

But no longer. Since August 2015 the yuan

has ostensibly been managed by reference

to a broadbasket ofcurrencies. Inprinciple

this is so the yuan’s value can better reflect

economic forces. In practice it simply al-

lows the yuan to move in a wider range

against the dollar, says Mansoor Mohi-ud-

din of NatWest Markets. Even this has lim-

its. If the yuan strengthens too quickly, it

will hurt China’s exports. If it weakens too

much, the dollar debts ofChinese firms be-

come more onerous. A sharp drop might

sparkdevaluation fears and capital flight.

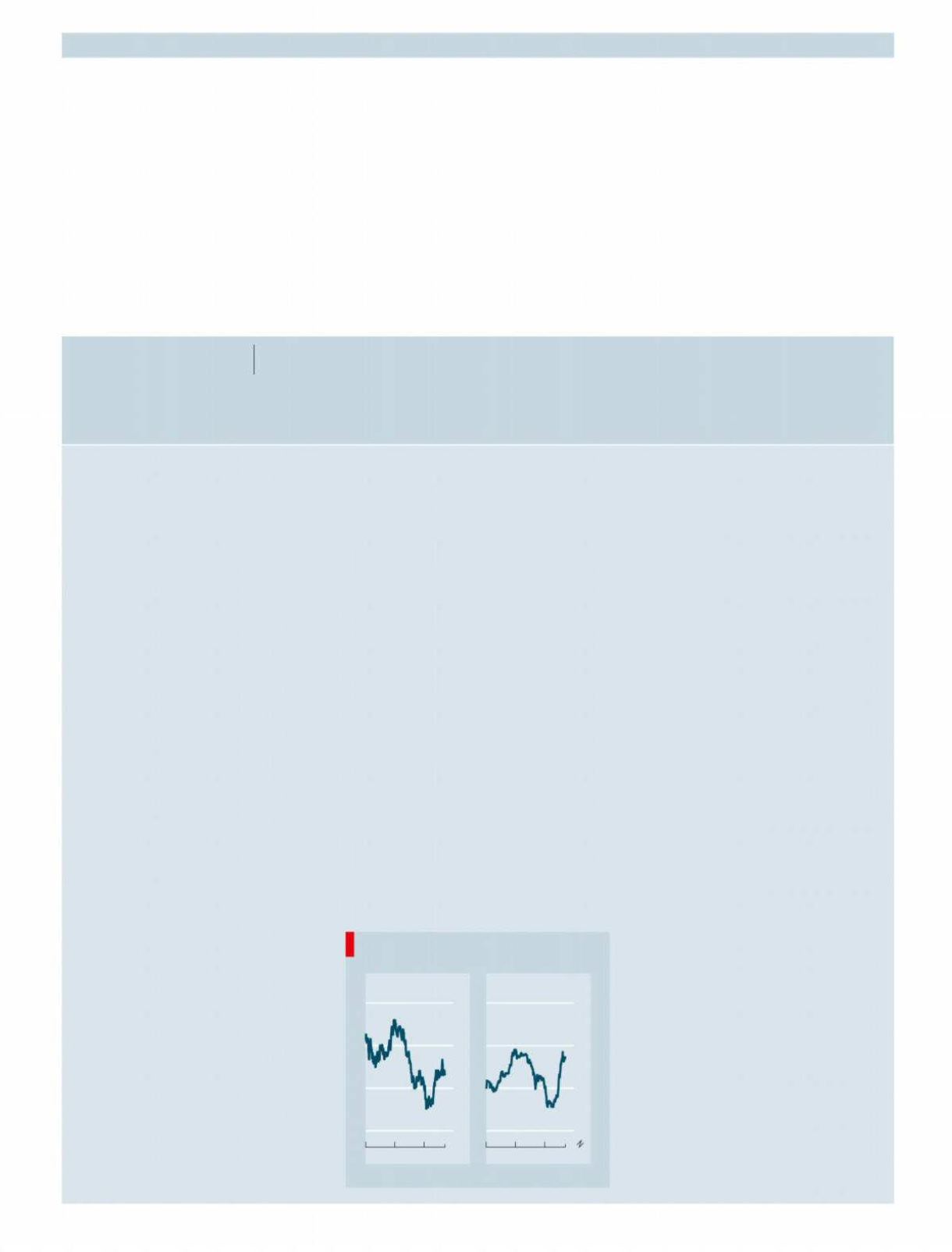

Yet in one regard, the yuan’s influence

is increasingly felt. Almost as soon as the

yuan was allowed to float a little more

freely, the currencies of economies that

do a lot of trade with China began to

move in tandem with it. The euro-dollar

exchange rate, for instance, has closely

tracked changes in the dollar-yuan rate re-

cently (see chart). When the yuan weak-

ened against the dollar in 2016, the euro

fell to a low of $1.05. When the yuan ral-

lied last year, so did the euro. This co-

movement is probably not a coincidence,

says Kit Juckes, of Société Générale, be-

cause the currencies of China’s other big

trading partners show the same pattern.

When the yuanmoves up or down, other

currencies follow it.

This is testament to China’s “soft pow-

er” in the foreign-exchange market, says

Mr Juckes. In large part China owes this

clout to its gravity in global trade. But it is

enhanced by the forward-guidance strait-

jacketwornby central bankers elsewhere.

Their transparency can be almost comi-

cal, as Mr Draghi’s comments show. By

contrast, little is knownaboutwhat China

plans. A shift in the yuan is a big signal.

China’s pull must now be reckoned

withwhen thinkingabout the outlook for

currency markets. A typical long-range

forecast for the euro is $1.30, some 10%

higher than where it trades now. That

forecast is close to estimates of the euro’s

purchasing-power parity, the exchange

rate that wouldmake the price of a basket

of goods the same in Europe as in Ameri-

ca. It seems a natural rate for the euro to

gravitate towards. But it will be hard for it

to reach that level unless China’s policy-

makers allow the yuan to rise against the

dollar. And who can say with confidence

that theywill?

The yuan show

Chasing the dragon

Source: Thomson Reuters

$ per euro

Inverted scale

Yuan per $

2016 17 18

1.3

1.2

1.1

1.0

2016 17 18

6.0

6.5

7.0

7.5

Buttonwood

HowChina’s currency sets the tone in the foreign-exchangemarket

or to launder money to the tune of “bil-

lions of roubles monthly”. The next year

Danske dropped, on cost grounds, a plan to

bring its Baltic subsidiaries onto its group

information-technology platform.

In 2013 a correspondent bank clearing

dollar transactions from the branch (J.P.

Morgan, says the

Financial Times

), ended

the relationship. That December an em-

ployee inEstoniablewthewhistle; soonaf-

terwards internal auditors pointed out

weaknesses in anti-money-laundering

practices. Even then Danske believed any

problems were being fixed and misjudged

their scale. Only in 2015 did the bank begin

a “proper run-off” of the non-resident port-

folio, the report says. The last accounts

were closed in early 2016.

Contrite, Danske is giving its gross in-

come from the branch over the nine years,

DKr1.5bn ($235m), to a fund to fight finan-

cial crime. But what took it so long to spot

trouble? Managers and systems failed at

pretty much every level, from Tallinn to

Copenhagen. The branch was allowed too

much independence, partly because it was

small, accounting for only0.5%ofDanske’s

assets. But it was also highly profitable,

making a return on allocated capital of

60% in 2013, when the Lithuanian branch

earned only 16% and the Latvian one 7%.

That should have rung bells. Employees

may have colluded with crooks: the bank

has reported eight to Estonian police.

Danske’s is just the most spectacular of

a string of money-laundering scandals af-

flicting Europe from the Mediterranean to

the Baltic. This month

ING

, a Dutch bank,

was fined €775m; its chief financial officer

lost his job. The European Commission re-

centlyproposed giving the EuropeanBank-

ing Authority, a supervisor, more power to

co-ordinate national authorities and even

to compel them to start investigations.

Tighter controls cannot come too soon.

7