The Economist

September 22nd 2018

Finance and economics 69

T

EN years on from the financial crisis,

the structure of American banking has

not changed. At its core are government-

guaranteed, and therefore cheap, deposits

that banks put to work, primarily through

lending. Deposits have become more im-

portant for bank funding in recent years;

governments have become increasingly

fussy about howthemoney is lent out. The

basic set-up is so entrenched thatmany be-

lieve there is no alternative.

A startup called

TNB

, short for The Nar-

row Bank, is questioning that assumption,

and causing a stir as a result. OnAugust 31st

TNB

filed a complaint in federal court

against the NewYorkFed, which, it alleges,

is breaking the lawby refusing to grant it ac-

cess to the central bank’s payment system.

The Fed has made no comment, but in re-

sponse to growing pressure, it has ac-

knowledged the complaint.

The case throws light on an unusual

business model. Led by a former head of

research at the NewYork Fed,

TNB

is based

on the idea of a narrow bank, which was

first suggested by professors at the Univer-

sity of Chicago as a response to the bank-

ing crisis of the 1930s. The proponents of

the “Chicago plan” argued that deposits

and lending need not be linked. A bank

could have a narrow mandate, restricting

itself tomerely receiving deposits.

The court filing suggests that

TNB

planned to do just that, taking deposits

from financial institutions (though not

fromconsumers) and redepositing themat

the Fed in order to take advantage of the

Fed’s interest rate on reserves, which is

1.95%. There would be no need for

branches or credit analysts. Compliance

costs would be minimal: as the bank

would not make loans, regulators would

need only an audit to show the bank’s

funds on account at the Fed covered its cli-

ents’ deposits. Tokeep costs lower still,

TNB

intends to avoid having deposit insurance,

which can cost up to 0.4% of assets. As the

money is invested with the central bank, it

is already guaranteed by the government.

Most American banks paymeasly rates

of interest ofunder0.1%, according toBank-

rate.com,a data provider. With its austere

model,

TNB

could plausibly provide a

competitive rate on deposits, while keep-

ing some of the spread between the Fed

rate and the interest it pays to customers.

The operating model is not without risks.

The Fed could cease paying interest to

banks, for example, a demand that both

America’s political parties have made at

times. But

TNB

, or a similarlyminded insti-

tution, could tweak the model in response

and invest its deposits in government secu-

rities instead.

The Fed’s silence has drawn criticism.

TNB

has received a temporary banking

charter fromConnecticut, so the state regu-

lator clearly deems it to be legal. The cen-

tral bank may worry that narrow banks,

which lend to neither companies nor indi-

viduals, could hamper the effectiveness of

monetary policy. Their business model

may also risk unsettling incumbent banks,

which could have large economic conse-

quences.

TNB

’s suit says that the Fed’s ac-

tions “have the effect of discriminating

against small, innovative companies” and

“privileging established, too-big-to-fail in-

stitutions”. The Fed may eventually be

forced to explainwhy that is a virtue.

7

Narrow banking

A hornets’ nest

NEW YORK

The Fed stalls the creation of a bank

with a novel businessmodel

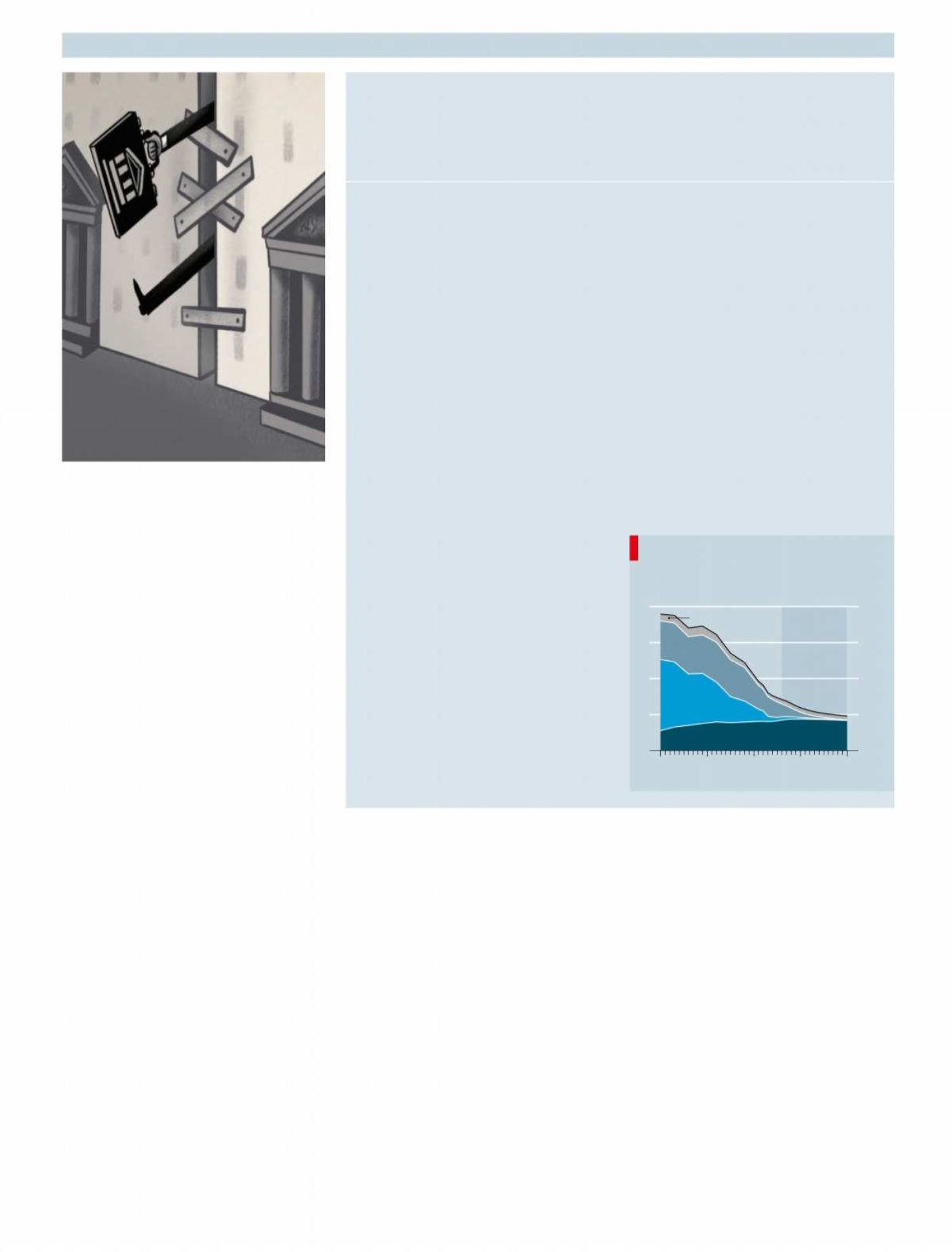

Poverty estimates

A thin gruel

H

ANS ROSLING, a Swedish academic

who died in 2017, became famous for

telling people that theworldwas faring

better than they believed. One of his

favourite exampleswas the rapid decline

in extreme poverty. Sadly, just as Ros-

ling’s elegant charts and YouTube talks

drilled that story into people’sminds, the

facts began to change.

On September19th theWorld Bank

released estimates for extreme poverty in

2015, defined as living on less than $1.90 a

day at 2011purchasing-power parity. The

good, Roslingish news is that poverty

continued to diminish (see chart). In 2015

the extreme poor numbered 736mpeo-

ple, or10% of theworld. The Bank’s best

guess for 2018 is 8.6%.

The bad news is that poverty is be-

coming harder to tackle. Over the past

fewdecades, rapid economic growth and

the expansion ofwelfare in Asia have

borne down on extremewant there. That

leaves sub-Saharan Africans as a growing

majority of paupers. African poverty is

especially intractable because ofweak

economies, high birth rates and the fact

that many poor Africans are not even

close to the $1.90 line. Between 2013 and

2015, theWorld Bank thinks, the poor

population of sub-Saharan Africa grew

from405m to 413m. As a result, the global

poverty rate is going down about half as

quickly as before.

The latest estimates contain another

nasty surprise. In theMiddle East and

north Africa the number of deeply im-

poverished people appears to have al-

most doubled in two years, from10m to

19m. Twowar-torn countries, Syria and

Yemen, explain this growth. It is hard to

be certain, given the difficulty of col-

lecting data. But theMiddle Eastern jump

hints at a broad change. Increasingly,

extreme poverty is found in chaotic,

ill-governed places. Figures on hunger

released earlier thismonth suggest that it

is growing in Venezuela.

There is a broader lesson in that, says

Laurence Chandy, director of data and

research at

UNICEF

, the

UN

Children’s

Fund. Theworld has been preoccupied

with the taskof pulling people out of

extreme poverty. But therewas always

another challenge, which is becoming

more pressing. Howcan entire pop-

ulations be prevented from falling into it?

Extreme poverty is changing, making it harder towipe out

Always with you

Source: World Bank

*Purchasing-power parity

Number of people living in extreme poverty, bn

Less than $1.90 a day at 2011 PPP*

FORECAST

0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

1990 2000

10

20

30

Sub-Saharan Africa

East Asia

& Pacific

South

Asia

Rest of world