48 Europe

The Economist

September 22nd 2018

2

root of the problem, but the facts do not

bear out this view. Portugal, southern Italy

and large parts of Spain have incomes per

head similar to parts of eastern Europe, yet

enjoy higher life expectancy. Scotland and

the north-east of England also have high

death rates from chronic disease. “What

you do with

GDP

is important,” says Mr

Vagero. Some countries prefer to spend

their money on social policy, others on

weapons. But in general, health systems in

eastern Europe are simply “not compara-

ble to western Europe,” says Mr Massay-

Kosubek.

“Health inequalities are unjust because

they can be prevented,” he goes on. Educa-

tion, access to clean air and improvements

in mental health could help. But preven-

tion policies are hard to get right, even if

they save money in the long run. With

more low-emission cars in western Eu-

rope, older, more polluting models end up

in eastern European markets.

EU

-wide

measures to reduce smoking, like plain

packaging and bans on public smoking,

have had some success. Alcohol consump-

tion could be tackled in a similar way. But

those who have kicked the smoking habit

often belong to the well-educated, richer

part of society. Improvements in health do

not always lead to greater equality.

Almost all

EU

members are collaborat-

ing on an action plan on health, and the

European Commission is running projects

to tackle the root of the health problem in

groups vulnerable to sickness. But not

everyone in Brussels supports such col-

laboration. Nationalist

MEP

s might seek to

take back control of public-health reform

after the European Parliament elections

next year by limiting the interpretation of

the

EU

’s mandate on health, some warn.

That couldhinderbringingEuropeans clos-

er, in sickness and in health.

7

W

HEN they returned this month after

their long summer holiday, Spain’s

politicians had much to contemplate.

There are signs that the economic recovery

is starting to flag. The Socialist minority

government ofPedro Sánchezmust strike a

balance between eliminating the deficit,

restoring social spending and raising busi-

ness taxes. A year after its independence

referendum, Catalonia’s government re-

mains sullen, awaiting the controversial

trial for rebellion of some of its imprisoned

former leaders. And Mr Sánchez has

pushed through an overdue law to remove

the remains of Francisco Franco, Spain’s

former dictator, from the triumphalist

mausoleumhe built outsideMadrid.

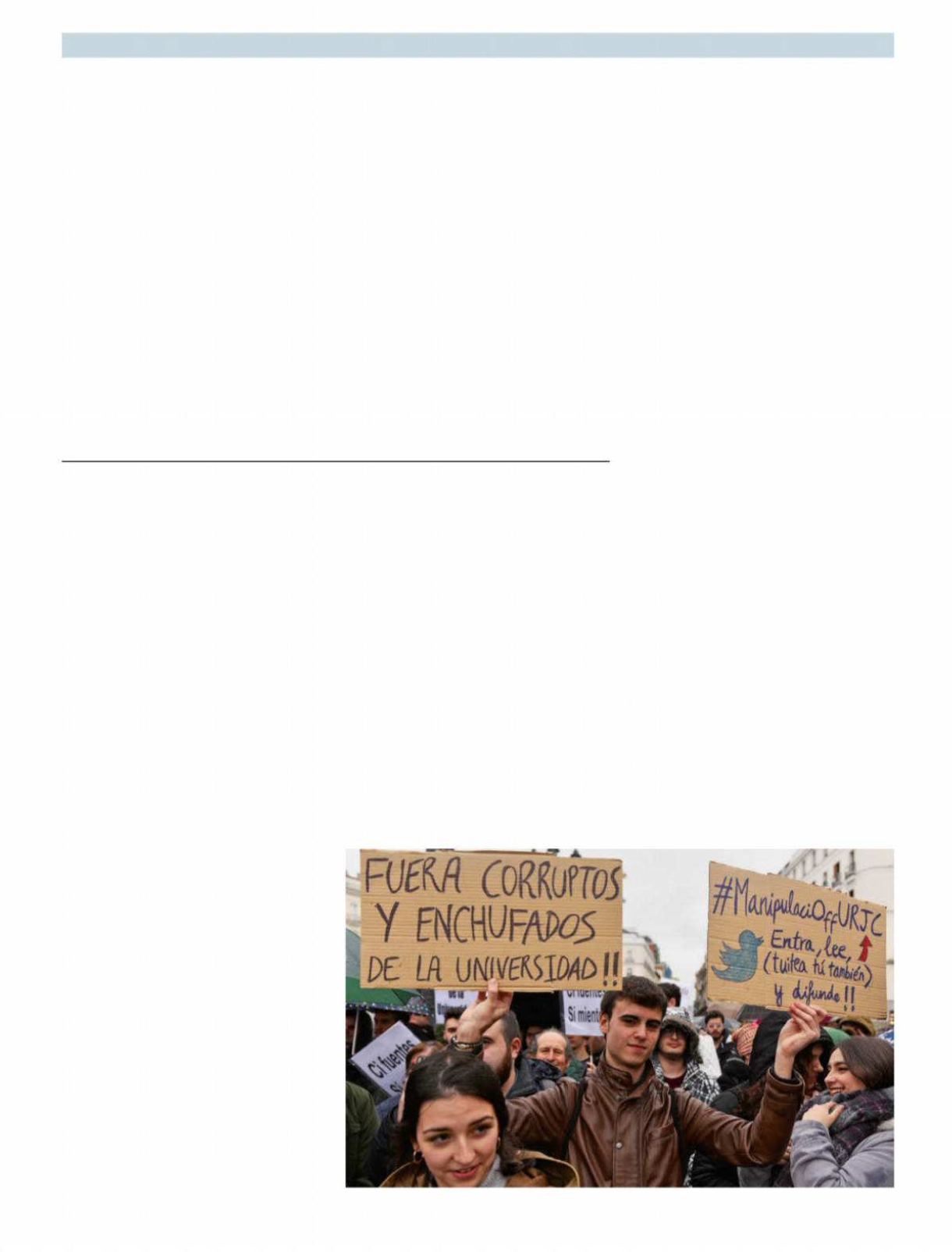

But Spanish politics have been con-

vulsed by a less uplifting matter: whether

the postgraduate degrees some of its lead-

ers boast of were fairly obtained. On Sep-

tember 11th Carmen Montón resigned as

health minister after it emerged that she

had been awarded a master’s degree in

2011 from King Juan Carlos University

(

URJC

) in Madrid without doing the requi-

sitework. In April the same fate had befall-

en Cristina Cifuentes, president of the Ma-

drid regional government and a member

of the conservative People’s Party (

PP

),

who had secured a bogus master’s from

URJC

’s Institute of Public Law.

Opposition newspapers have claimed

that Mr Sánchez’s doctoral thesis was pla-

giarised or written by someone else. The

thesis, entitled “Innovations in Spanish

economic diplomacy”, is hardly an aca-

demic ground-breaker. It was approved by

a low-powered examination panel at a

private university. But there is no evidence

that it was not his ownwork.

That allegation looked like a smoke-

screen to protect Pablo Casado, the new

PP

leader, who is potentially in far more seri-

ous trouble. In 2008 he obtained the same

degree as Ms Cifuentes. He admits that he

was credited with 18 of 22 assignments

without doing any work. He insists he did

nothing wrong. But in July a judge ruled

that his degree could have constituted an

undue gift; she has asked the supreme

court to lift Mr Casado’s judicial immunity

in order to charge him. The institute is now

closed and its founding director charged

with fraud.

All this sets the bad example that the

way to get ahead is through contacts, not

merit and hard work. Like

URJC

, several

other Spanish universities have become

party fiefs. But what explains the politi-

cians’ need to inflate their credentials?

There are a handful of genuine intellectu-

als in theCongress. But nowadays the aver-

age Spanish politician is a party hack ply-

ing a discredited trade, argues Victor

Lapuente, a political scientist at Gothen-

burg University. “Getting a postgraduate

degree is a way of seeming to be a trained

professional,” he says.

The fuss over degrees is also a sign that

an election may not be far off. Mr Sánchez

took office in June after dispatching Mari-

ano Rajoy, the

PP

prime minister, in a cen-

suremotion. After years of austerity under

the dour Mr Rajoy, Mr Sánchez, aged 46

and with an easy charm, brought a breath

of fresh air. But his Socialists have just 84 of

the 350 seats in parliament. He has gov-

ernedwith gestures, such as Franco’s exhu-

mation, and with

U

-turns (having initially

welcomed a migrant ship, his government

is nowsendingmigrants back toMorocco).

Mr Sánchez says hewants to see out the

parliament’s term until 2020. Despite his

inexperience, he has the sense of opportu-

nity of a more seasoned politician. To em-

barrass Mr Casado, this week he proposed

a constitutional amendment to curb par-

liamentary immunity, a popularmove. But

he may struggle to get the 2019 budget ap-

proved. Having lifted the Socialists to a

narrow lead in the polls, he may be tempt-

ed at anymoment to go to the people.

7

Spain

A question of degrees

MADRID

The politics of the permanent election campaign

Devaluing the currency