44 Middle East and Africa

The Economist

September 22nd 2018

1

B

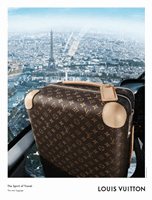

Y ANY standards, the international air-

port of Niger’s capital is a dozy spot—

unless you are a French military air-traffic

controller. On the civilian side of the ram-

shackle airport a few planes come and go.

The contrast with the military side could

not be starker. Helicopters and military

transport planes sit on the apron. Mirage

warplanes sit ready for action. This is the

aviation hub of Barkhane, France’s four-

year-old counter-terrorism operation in

the Sahel, which has its headquarters in

Chad, and also operates across Burkina

Faso, Mali, Mauritania andNiger.

The French-led operations have attract-

ed less attention than has

AFRICOM

,

America’s military command for Africa,

which conducts raids and drone strikes

from Somalia to Libya. Yet France’s role in

the region is growing in importance, partic-

ularly as America has been considering

withdrawing most of its special forces

from Africa since four soldiers were killed

inNiger a year ago.

Barkhane costs the French taxpayer

some €600m ($700m) a year. It ismade up

of 4,500 soldiers fighting Islamist groups in

Mali and, to a lesser extent, in Burkina Faso

and Niger. Its zone of operations is nearly

as big aswestern Europe. Twelve Barkhane

soldiers have died since 2014.

Apart from its own counter-terrorism

operations, France is an “organiser and co-

ordinator” for other forces in the region,

says Christian Cambon, president of the

French Senate’s defence committee. This is

apparent at the base in Niamey. Behind

high walls French troops lob

boules

in a

game of

pétanque

or play table tennis. Ger-

man troops drink in the bar. An American

airbase is next door; another is being built

in Agadez, to the north. France also helps

the

G

5, a regional counter-terrorism force

comprising troops from Burkina Faso,

Chad, Mali, Mauritania andNiger, and bol-

sters the large

UN

force inMali.

General Bruno Guibert, Barkhane’s for-

mer commander, recently said that French

forces had killed or captured 150 jihadists

this year alone inMali and Niger. More im-

portant, they have kept the jihadist groups

scattered and denied them territory for

more permanent bases.

Yet France’s approachalsohas its limita-

tions. The French “are very directed at tar-

geted killings right now,” says Andrew Le-

bovichof the EuropeanCouncil onForeign

Relations, a think-tank. Barkhane has ex-

cellent ground-level intelligence, he says,

but it is sometimes less good at strategy. For

example, the French have made alliances

with ethnically based militias in Mali that

have tarnished Barkhane by association,

by allegedly massacring their enemies or

getting the French to assassinate rivals in

their own camp. General Guibert says his

zone of operations is so big that his troops

cannot be everywhere. “Barkhane”, he ad-

mits “won’t bring victory. It is only politics

that can do that.”

If Barkhane had not been set up in the

Sahel, jihadists would almost certainly

have been able to consolidate their forces

and takemore territory. But an unintended

consequence of the operation is that it is

helping to prop up authoritarian regimes.

The French are damned if they do send

troops, damned if they don’t. They are not

the first to find themselves caught in an

anti-insurgency trap.

7

French forces in Africa

Sahel or high water

NIAMEY

French forces are playing a greater role infighting jihadists

I

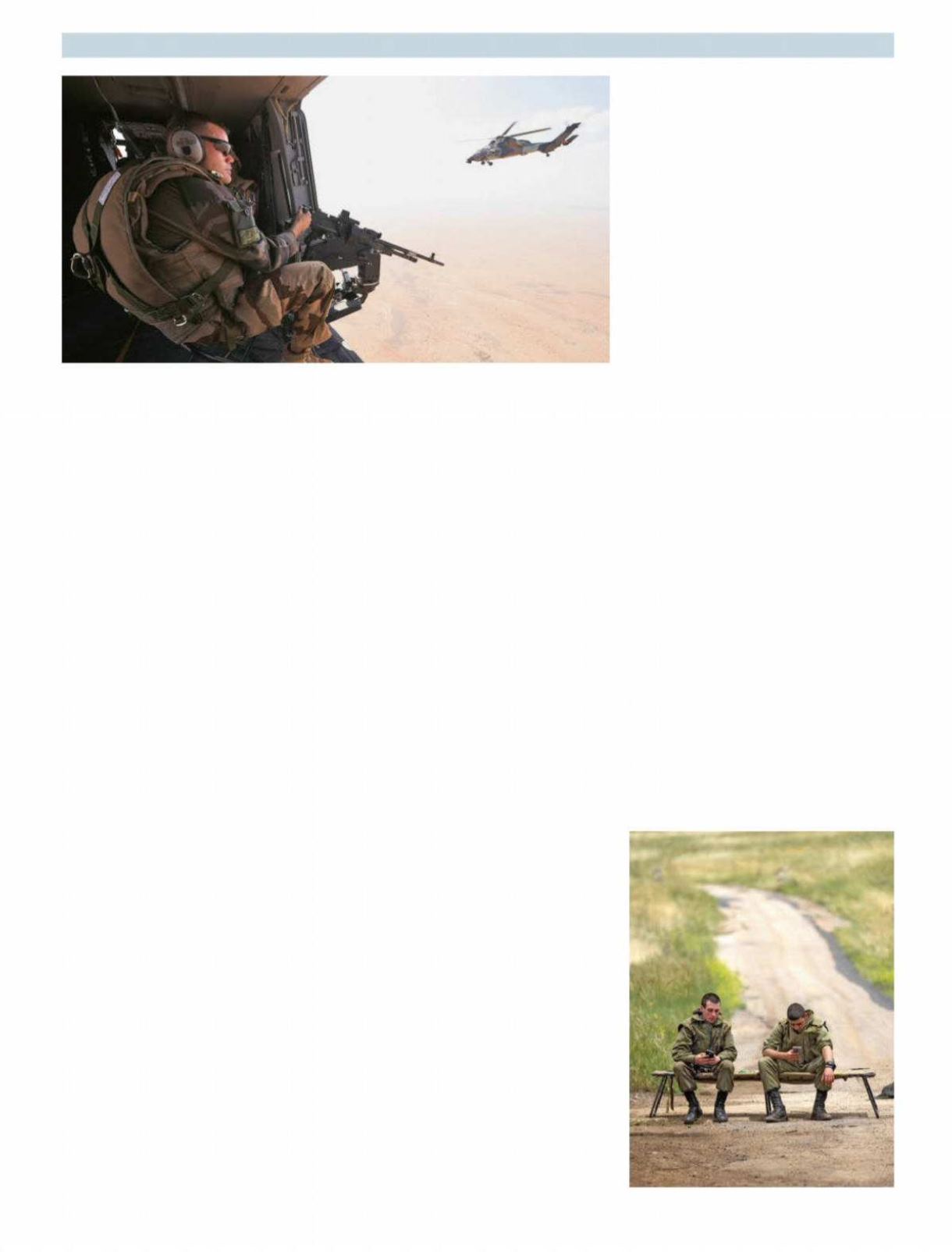

N THE twin towers of Israel’s Ministry of

Defence and the neighbouring head-

quarters of the Israel Defence Forces (

IDF

)

in central Tel Aviv, the brass hats summed

up the end of the Jewish year with their

customary briefings to politicians and

journalists. With slideshows of maps and

graphs showing why Israel’s armed forces

are still the best in the region, the generals

displayed their success in knocking out Ira-

nian targets in Syria and stopping Hamas

frommenacing Israel fromGaza.While do-

ing so, theyhave prepared their combat un-

its to fight an all-out war, should they be

obliged to.

But one old soldier insisted on spoiling

the party. Major-General Yitzhak Brik re-

tired from active service in 1999 but has

served as the army’s ombudsman for the

past decade. Last month he presented the

cabinet and somemembers of the Knesset,

Israel’s parliament, with a secret report. It

warned that Israel’s forces, especially the

army, are not ready for amajorwar.

Stung by these accusations, the respect-

ed chief of staff, Lieutenant-General Gadi

Eisenkot, responded by insisting that the

army he has led for nearly four years is in-

deed ready for battle and that its units have

undergone an unprecedented number of

live-fire exercises. Both generals say they

have based their assessments on raw data

and direct impressions from the field. But

frequent calls on the army to conduct inter-

nal-security operations have disrupted its

Israel’s military preparedness

Stand uneasy

JERUSALEM

Ageneral tells Israel that its armymust

be still readier to fight

Come back later, when we’re ready