The Economist

September 22nd 2018

Middle East and Africa 41

2

muchmore urban than east Africa, but has

a higher fertility rate.

Three things could drastically change

the picture, however. First, more African

governments could promote family plan-

ning. Ethiopia, Malawi and Rwanda have

done so, and their birth rates are dropping

faster than average. Perhaps the starkest

change is in Kenya. Alex Ezeh of the Centre

for Global Development, a think-tank in

Washington, remembers showing Kenyan

politicians evidence that wealthy people

both desired and had small families,

whereas the poor wanted large families

and ended up with even larger ones. The

government invested in clinics and propa-

ganda, to some effect. Household surveys

show that 53% of married Kenyan women

used effective contraception in 2014, up

from 32% in 2003. Kenya’s neighbour, Tan-

zania, is at least a decade behind.

The second cause for optimism is edu-

cation. Broadly, the more girls go to school

in a country, the lower that country’s birth

rate. This seems to be more than just a cor-

relation: several studies, in Africa and else-

where, have found that schooling actually

depresses fertility. Toattend school—evena

lousy school where you barely learn to

read—is to gain a little independence and

learn about opportunities that your par-

ents had not envisaged for you.

Researchers at the International Insti-

tute for Applied Systems Analysis in Aus-

tria suggest that Africa’s schools are about

to drive a large change. They point out that

education spendingweakened in someAf-

rican countries in the 1980s as govern-

ments scrambled to cut budget deficits.

Girls’ schooling, which had been increas-

ing, flattened. It is probably not a coinci-

dence that African fertility rates fell little in

the 2000s, when that thinly educated co-

hort reached womanhood. But school en-

rolments have risen since then. If educa-

tion really makes for smaller families, that

will soon be apparent.

The third profound change would be

stability in the Sahel. The semi-arid belt

that stretches through Burkina Faso, Chad,

Mali, Niger, northern Nigeria and Sudan is

lawless in parts and universally poor.

Child death rates are still shockingly high

in places. Partly as a result, and also be-

cause women’s power in the Sahel is un-

dermined by widespread polygamy, peo-

ple still desire many children. The most

recent household survey of Niger, in 2012,

found that the average woman thought

nine the ideal number.

Progress on all three counts depends

mostly on African politicians. It falls to

them to create more and better schools,

provide security for their people and in-

vest in family planning. They, not foreign

observers, need to conclude that their

countries would be wealthier if they had

rather fewer children. Like somuch in Afri-

ca, almost everything depends on the

quality of government. And that, sadly, is

hard to decree.

7

2

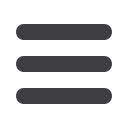

Africa is different

Sources: IMF;

UN Population Division

*Purchasing-power parity

GDP and fertility

GDP per person, constant 2011 $’000 at PPP*

Fertility rate, births per woman

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

0 1 2 3 4 5 6

Nigeria

Tanzania

1990

1990

2016

2016

India

1990

2016

Child marriage

Growing up too early

I

NAdusty village in southernNiger,

Fatia holds her daughter close to her

breast, smiling, though the baby looks

much too large for her. Four years ago she

married at the age of16, she reckons, but

shemay have been younger. Since then

she has had two children.

Three out of four girls inNiger are

married before they are 18, giving this

poorwest African country theworld’s

highest rate of childmarriage. TheWorld

Bank says it is one of only a very small

number to have seen no reduction in

recent years; the rate has even risen slight-

ly. The country’sminimum legal age of

marriage for girls is 15, but some brides

are as young as nine.

Across Africa childmarriage stub-

bornly persists. Of the roughly 700m

women living todaywhoweremarried

before theywere 18, 125mare African.

Among poor rural families like Fatia’s the

rate has not budged since 1990. The

UN

Children’s Fund (

UNICEF)

estimates that,

on current trends, almost half theworld’s

child brides by 2050will be African.

But some countries have shown they

can keep young girls out ofwedlock. In

Ethiopia, once amongAfrica’s top five

countries for childmarriage, the practice

has dropped by a third in the past decade,

theworld’s sharpest decline, says the

World Bank. The government wants to

eradicate childmarriage entirely by 2025.

Ethiopia offers lessons for other Afri-

can countries. For one thing, it shows that

in religious societies youmust win over

imams and priests. Guday Emirie of

Addis Ababa University notes that in one

district a local priest, having been public-

ly shamed formarrying offhis own

daughterwhen shewas a child, has since

been preaching against the practice. It has

nowbeen eliminated in his district.

Conservative imams inNiger, by contrast,

often invoke the Prophet’smarriage to a

young girl, according to tradition.

After a decade of strong economic

growth, Ethiopia’s poverty rate is now

half that inNiger, one of theworld’s

poorest countries. Many of its people,

says Lakshmi SundaramofGirls Not

Brides, an

NGO,

believe that “childmar-

riage is away of reducing the number of

mouths to feed”, as the bridemoves in

with another family.

Education is evenmore vital. “You

generally don’t find a child bride in

school,” notes a

UNICEF

expert in Ethio-

pia. Its government spendsmore on

education as a proportion of its budget

than other African countries. More than a

third of its girls, a big increase, enrol in

secondary schools. InNiger the figure is

less than a fifth.

Curbing childmarriage could lower

fertility rates by about a tenth in coun-

tries like Niger and Ethiopia. Doing so

would immeasurably improve the lives

ofwomen like Fatia. On herwedding

night, she says she begged her husband

not to force himself on her. “Hewas

bigger thanme. It hurt toomuch,” she

says, looking down at her daughter.

ADDIS ABABA AND NIAMEY

Childmarriage is proving stubbornlypersistent

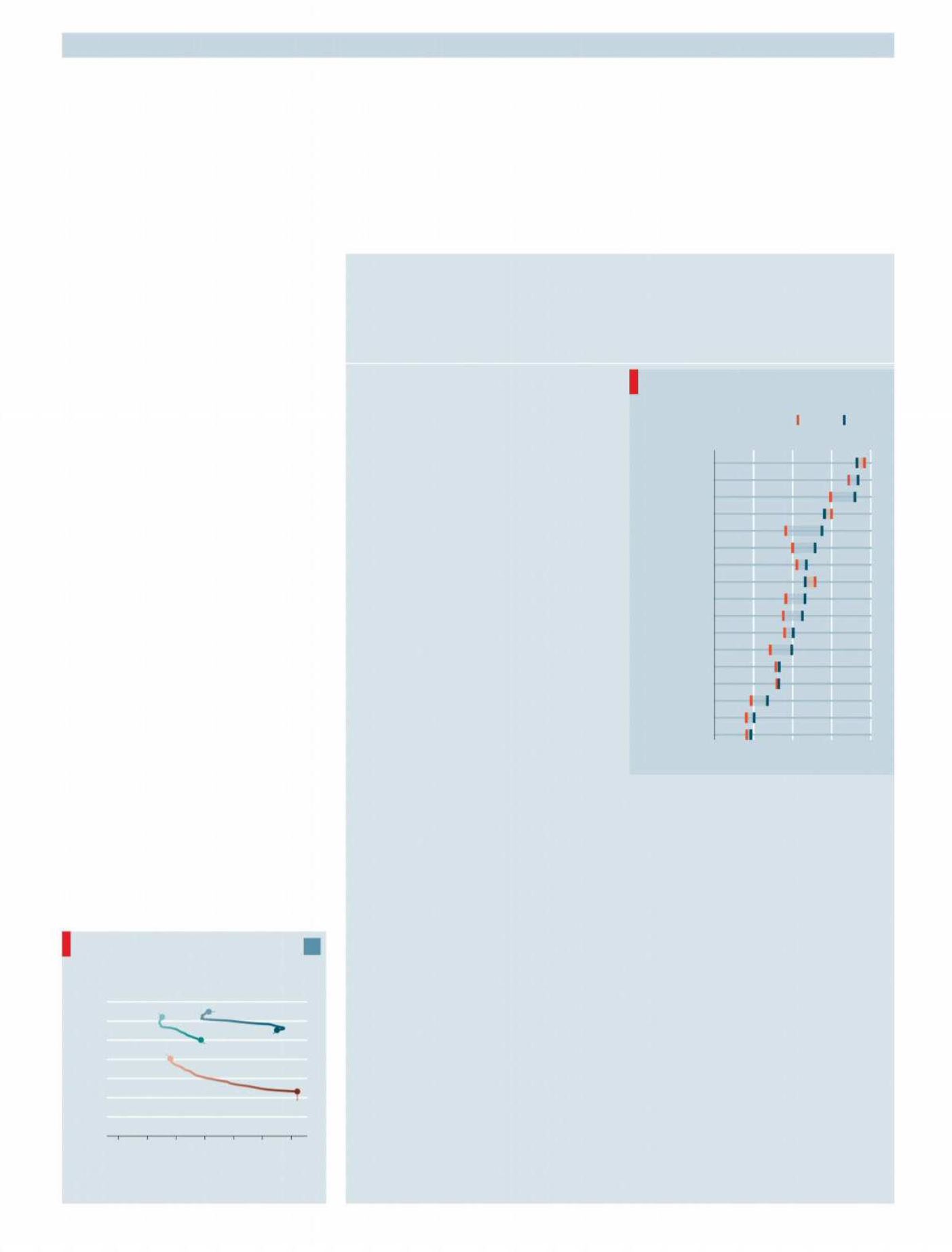

Cradle snatchers

Sources: World Bank; International

Centre for Research on Women

Share of women married

before 18, by age group

2017, %

0

20 40 60 80

Egypt

Indonesia

Pakistan

Ivory Coast

Senegal

Congo

Zambia

Mauritania

Uganda

Mozambique

Nigeria

India

Ethiopia

Mali

Bangladesh

Chad

Niger

18-22 23-30