36 Asia

The Economist

September 22nd 2018

E

ARLIER this year a neighbour dropped

by the Chundawats’ house in the north-

ern suburbs of Delhi, wondering why his

friend Lalit had not opened his nearby

shop.Whenhe let himself in the reasonbe-

came clear. Everyone inside—11 people

from three generations—was dead. Two

brothers, theirwives, a sister and their chil-

dren dangled from the ceiling in a hallway,

suspended by ropes, blindfolded, hands

tied. The family matriarch, 77-year-old Na-

rayani Devi, lay strangled nearby. Only

Tommy, a dog, survived.

Police say the deaths were a mass sui-

cide, most likely prompted by occult be-

liefs. Yet, strange though the incident ap-

peared, the Chundawats’ death was only

one of numerous collective suicides across

India this summer. In July in the state of

Jharkhand alone, two families killed them-

selves, driven by the more prosaic motive

of despair over debt.

Suicide is often seen as a rich-world

problem, but is all too common in India.

New research, published this week in the

Lancet

, a medical journal, reveals that In-

dia suffers from perhaps 230,000 a year,

nearly double previous estimates. With

18% of the world’s population, it is respon-

sible fornearlya quarter ofsuicides among

men worldwide, and almost four out of

ten among women. Suicide is the leading

cause of death for all Indians between the

ages of15 and 39, and for Indianwomenbe-

tween the ages of15 and 49.

The paper’s lead author, Rakhi Dan-

dona of the Public Health Foundation of

India, says that previous estimates for sui-

cides relied solely on police reports. These

tended to undercount, not least because

until last year Indian law considered sui-

cide, as well as “abetment” of it, a crime.

Her team instead extrapolated results for

the past 25 years from a range of nation-

wide medical records, including nearly

half amillion autopsy reports.

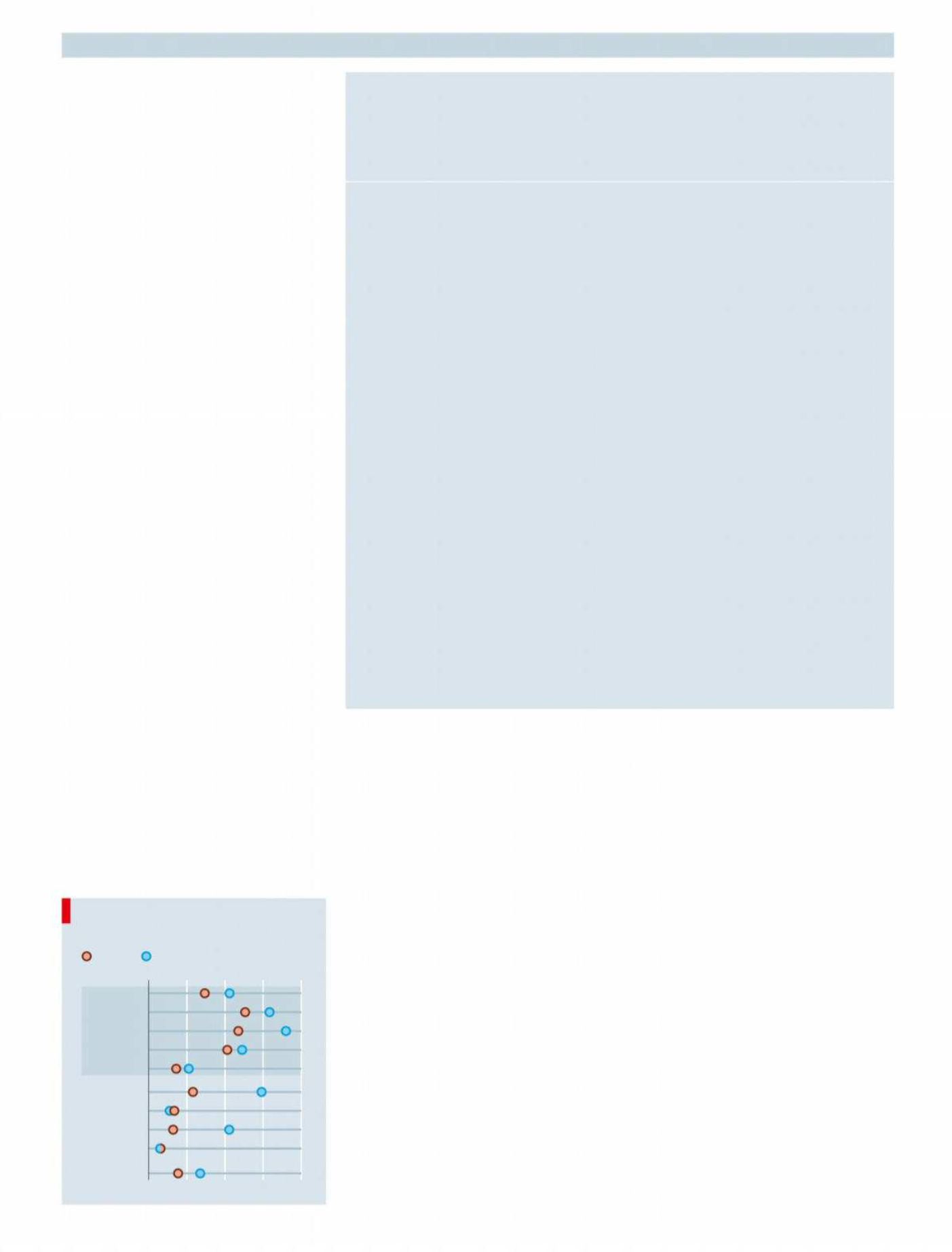

India’s suicide rate, like the global one,

is falling. But whereas the rate among

womenworldwide has fallen by half since

1990, and in China by an astonishing 70%,

in India it has droppedby just 25%. And just

as South Korea and Russia have relatively

high suicide rates, butmostMuslim-major-

ity countries relatively low ones, there is

stark geographical variation among Indian

states (see chart). Awoman in the southern

state of Tamil Nadu, for example, is ten

times more likely to commit suicide than

one in jungle-boundMizoramin the north-

east. Men in the poorest state, Bihar, kill

themselves at a quarter of the rate of those

in bustling Karnataka, the heart of India’s

technology industry.

Partly because suicide was criminal-

ised for so long, there has been little re-

search into its causes. “The determinants

for such huge differences are not under-

stood,” says Dr Dandona. “South Indians

may be inclined to internalise their trou-

bles, whereas northerners verbalise, but

that is pure speculation.” There have been

no studies of differences among India’s re-

ligious groups, although there is some evi-

dence that Muslims are much less likely

than Christians and Hindus to do them-

selves in. Andnoone knowswhether caste

plays a role, although suicide rates seem to

rise with wealth and urbanisation, before

falling again as the newly urbanised grow

accustomed to their environment.

What does seem sure is that suicide

rateswill continue to fall, perhaps dramati-

cally. The ubiquity of televisions and mo-

bile phones has diminished individual iso-

lation, for example for wives oppressed by

demanding mothers-in-law. It has also

made more Indians aware and accepting

ofways to seekhelp formental problems.

De-criminalising suicide has also made

it easier todiscuss and investigate the issue.

Earlier this year the Supreme Court quoted

an eloquent argument for a more compas-

sionateview: “If the right to lifewere onlya

right to decide to continue living and did

not also include a right todecide not to con-

tinue living, then it would be a duty to live

rather than a right to life.”

7

Suicide in India

Deadly reckoning

DELHI

Astudyfinds that farmore Indians kill

themselves than previouslyassumed

A miserable toll

Sources: WHO; India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative

Suicide rate per 100,000 population, 2016

0

10 20 30 40

World average

India

Bihar

West Bengal

Karnataka

Tamil Nadu

Bangladesh

South Korea

Pakistan

United States

Male

Female

Politics in Pakistan

Back on the street

E

VEN for a life characterised by drastic

reversals of fortune, it has been a

dizzyingweek for Pakistan’s thrice-

ousted primeminister, Nawaz Sharif.

Therewasmisery on September14th,

when hewas granted a fewhours’ parole

from the 11-year prison sentence he began

serving in July to attend the funeral of his

wife, Kulsoom. Then, on September19th,

therewas unexpected delight. The Islam-

abadHigh Court announced it would

suspend his sentence, alongwith the

eight-year termgiven to his daughter,

Maryam, for the duration of their appeal.

The court’s terse order offered little

explanation. But during the hearing that

preceded it Justices AtharMinallah and

Miangul Aurangzeb echoedwidespread

criticismof the original verdict. Prosecu-

tors had failed to provide evidence of

their claim that Mr Sharif’swealthwas

ill-gotten, saidMrMinallah, and had

relied instead on the “mere presumption”

of guilt. The casewas needlessly rushed,

addedMr Aurangzeb (the 174-page verdict

containsmany garbled phrases, such as

“brushacite” instead of “brushed aside”).

Such scepticism from the benchmakes

an eventual acquittal likely, lawyers say.

Supporters ofMr Sharif’s political party,

the PakistanMuslimLeague-Nawaz

(

PML-N

), celebrated in the streets.

Mr Sharif claims that the army, with

which he often clashedwhile in power,

orchestrated the case against him to hurt

the

PML-N

’s chances in the election on

July 25th. If so, it worked. The

PML-N

lost

power to the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf

(

PTI

) of Imran Khan. But the

PTI

’s suppor-

ters retort that, if there had been a con-

spiracy to foil Mr Sharif, whywas he

released? One reasonmay be that the

election is over, so the imprisonment has

served its purpose. Others argue that the

judiciary is not infinitely pliable. The two

judges concerned are considered in-

dependent and liberal-minded.

Eitherway, for the time being, Mr

Sharif and his daughter are free to do

what they intendedwhen they left Kul-

soom in a coma in London and returned

to Pakistan in early July: rally their party.

In particular, Maryam, whose reputation

has been buoyed by herwillingness to

face prison, who is furious at what has

happened to her family andwho is

thought to beMr Sharif’s chosen succes-

sor, is likely to start agitating against Mr

Khan. He, after all, made her father’s life

difficult when the

PML-N

was in power.

“Imran’s goose is cooked,” predicts one

jubilant party leader.

Karachi

Anunexpected court decision energises the former ruling party