The Economist

September 22nd 2018

Europe 47

2

activist was detained on September 11th.)

Officials inAnkara are now talking about a

newstart in relationswith the

EU

.MrsMer-

kel’s government, meanwhile, has come

out against America’s decision to impose

economic sanctions on Turkey, scrapped

its own export-guarantee limits and made

it clear that a collapse of the Turkish econ-

omy is in nobody’s interest. According to a

report in

Der Spiegel

, two German compa-

nies, Siemens andDeutsche Bahn, are hop-

ing to take part in a €35bn overhaul of Tur-

key’s rail network. Turkey would like

Germany to help finance the project.

Caution is in order. Much as Mr. Erdo-

gan might like to thumb his nose at the In-

ternational Monetary Fund, the likelihood

of Germany giving Turkey a bail-out with

few strings attached is close to zero. “Ger-

many will not go behind the

IMF

’s back,”

saysMarc Pierini, a former

EU

ambassador

to Turkey. Given Turkey’s sorry rule-of-law

and human-rights record, any progress in

its accession talkswith the

EU

is also out of

the question. In theory, Turkey couldmake

some headwaywith the Europeans in talks

on a new customs union and visa-free tra-

vel. In practice, these would require eco-

nomic and political reforms that the Turk-

ish government appears to have no

intention of passing. Mr Erdogan did not

spend years constructing a system of pa-

tronage that reaches into most corners of

the economy and the bureaucracy just to

dismantle it at the first sign of a crisis.

7

S

LUPSK, a townof some100,000 inhabit-

ants near Poland’s Baltic coast, is these

days a favourite place to tie the knot. “It has

become a Polish Las Vegas,” says Robert

Biedron, the mayor, who has married

some 140 couples. Yet Mr Biedron, who is

openly gay (still a rarity in Polish politics),

cannot marry his partner. Unusually for a

Polish politician, he is also secular, as well

as something of a green.

As the socially conservative Law and

Justice (

P

i

S

) government continues to chip

away at Poland’s institutions, most recent-

ly the supreme court, the 42-year-old

mayor has emerged as the hope of the Pol-

ish liberal left. Yet emulating the success of

Emmanuel Macron, who emerged from

popular near-obscurity to become

France’s president in 2017 at the head of a

brand-newparty, will be a tall order.

Still, he has a chance. For all his appeal

toWarsawmillennials, Mr Biedron knows

small-town Poland well. Now a

P

i

S

heart-

land, the rural south-east where he grew

up was not an easy place to be a gay teen-

ager in the 1990s. In his 20s he founded a

pressure group, Campaign Against Homo-

phobia. After a stint in parliament, he ran

for mayor of Slupsk as an independent in

2014, winning 57% in the second round.

Mr Biedron has tested out his vision for

a Poland in which no one is left behind.

From the neo-Gothic town hall of Slupsk,

he has slashed debt, increased transpa-

rency and banked on sustainable develop-

ment. Guests are served water from the

tap, rather than plastic bottles. Led by Mr

Biedron, a dozen Polish mayors have

formed a network of “progressive towns”,

tackling problems from depopulation to

air pollution. In Poland, this amounts to

revolutionary stuff.

Although critical of

P

i

S

’s illiberalism,

Mr Biedron has little sympathy for its arch-

rival, the centrist Civic Platform (

PO

),

which governed from2007 to 2015. In pow-

er,

PO

neglected “everyday democracy”,

based around local public services rather

than distant institutions like the supreme

court, he says. To increase popular partici-

pation in politics, he recentlywrote a book

on democracy for children.

As the European Commission consid-

ers cutting off money for countries where

the rule of law is at risk, ie, Poland and

Hungary, Mr Biedron is wary of penalising

ordinary people for their government’s

misdeeds. Instead,

EU

cash should go di-

rectly to local officials,

NGO

s and business-

es, bypassingWarsaw, he suggests.

With Poland split between

P

i

S

’s sup-

porters and critics, Mr Biedron is aware of

his own power to divide or unite. At a re-

cent talk in north-eastern Poland, he was

greeted by a man wearing a

T

-shirt with a

homophobic slogan (

zakaz pedalowania

,

which translates loosely as “no faggotry”).

Rather than call security, Mr Biedron invit-

ed him to pose for a photo with him (the

man obliged).

Popularity, though, comeswith high ex-

pectations. Already, polls put Mr Biedron

among the top three contenders for the

presidency in 2020, after Andrzej Duda,

the

P

i

S

-aligned incumbent, and Donald

Tusk, who might return to Poland after the

end of his term as president of the Euro-

pean Council. Mr Biedron declines to say

whether he is planning to run, but this

month said that hewill not seekre-election

in Slupsk and will instead establish his

own “progressive” movement ahead of

the European Parliament elections next

spring. Those, he says, will be a “test” be-

fore the general electionnext autumn, after

no left-wing parties made it into parlia-

ment in the previous one. He shrugs off

criticism in

PO

circles that thiswill split the

anti-

P

i

S

vote and dash any hope of ousting

the current government. “They should be

cheering us on,” he says.

7

Poland

Taking on PiS and

Civic Platform

SLUPSK

Meet Robert Biedron, a young gay

Polishmayor

F

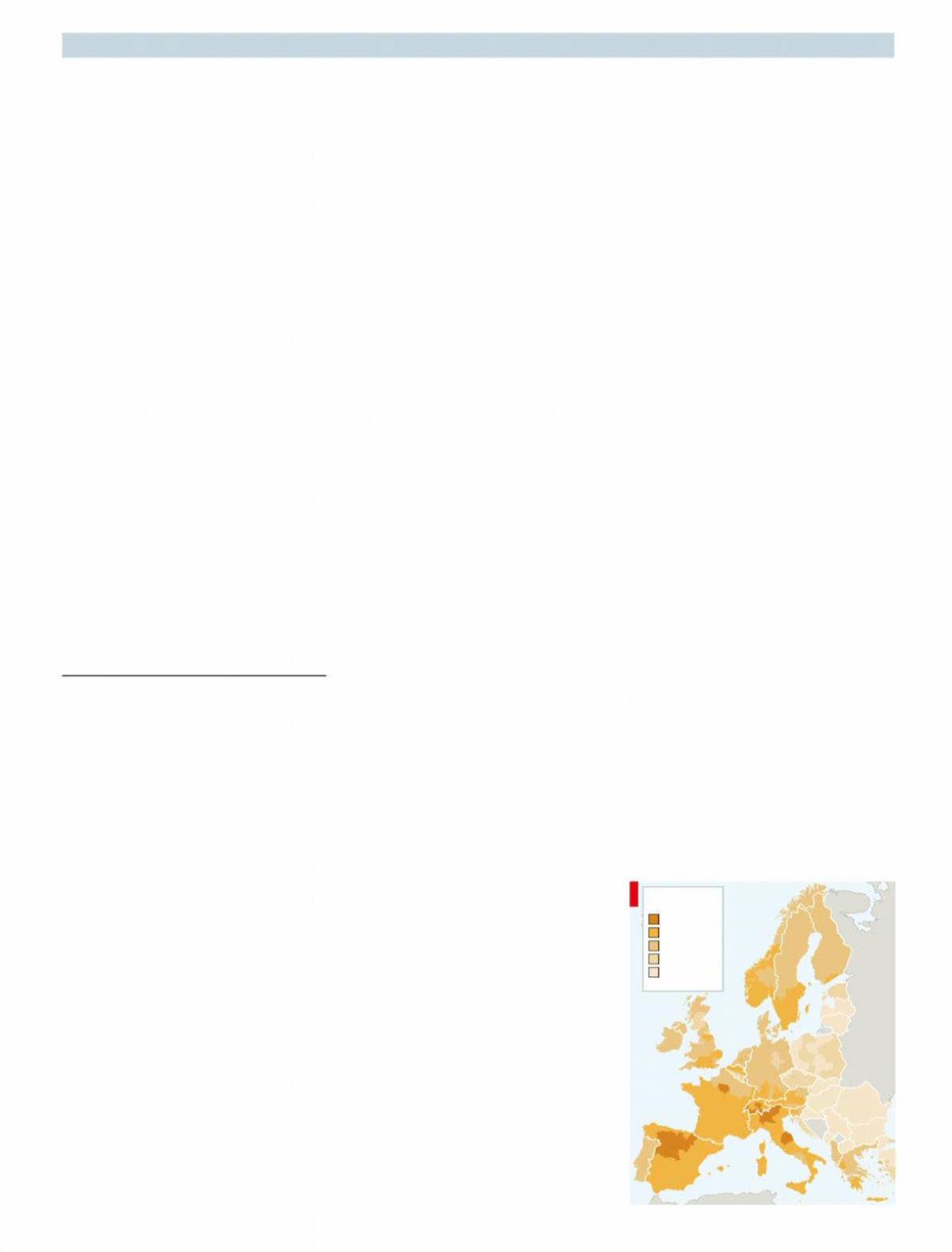

ROMStettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the

Adriatic, a health divide has fallen

across Europe. Although in global terms

citizens of the

EU

live long (2.5 years more

than inAmerica and 4.6 yearsmore than in

China), the continent is divided. At the far-

thest ends of the spectrum, Spaniards from

Madrid can expect to live to 85, but Bulgari-

ans from the region of Severozapaden are

predicted to live just past their 73rd birth-

day—a gap of almost 12 years. The only ex-

ceptions are Slovenia, which scrapes in

above the

EU

average, and Denmark,

which falls a fraction below.

It was not always that way. In the

mid-1960s Latvians and Lithuanians still

blew out as many birthday candles as the

citizens of Cyprus and France. But “the po-

litical division of Europe is important,”

says Denny Vagero, a professor of medical

sociology at Stockholm University. After a

long period of convergence caused by re-

ductions in child mortality, the east of the

continent gradually fell behind after the

iron curtain descended.

According to ZoltanMassay-Kosubek of

the European Public Health Alliance

(

EPHA

), an

NGO

, eastern Europe is home to

more smokers and more heavy drinkers.

“This is the major source of the gap,” he

says. Bad habits and unhealthy environ-

ments are contributory factors to chronic

illnesses such as cancer, diabetes and heart

disease. Hungarians face the poorest odds

when it comes to chronic ill-health, but

rates are also high in much of Poland, Slo-

vakia, and Croatia.

Money might be thought to be at the

Mind the gap

Europe’s chronic

health problem

The final curtain falls earlier in eastern

Europe

84.0+

80.0-81.9

82.0-83.9

78.0-79.9

<78.0

Life expectancy

At birth, 2016

Source: Eurostat

1