58 International

The Economist

May 5th 2018

2

become more needy. But a recent

IMF

re-

port argues the greatest boost to recruiting

and keeping women in paid jobs comes

from public spending on early-years edu-

cation and child care.

Employers can do more too, most obvi-

ously by providing flexible working condi-

tions, such as the ability to work remotely

or at unconventional hours, and to take ca-

reer breaks. Fathers need to be able to en-

joy the same flexible working options as

mothers. Some women are kept out of the

workforce by discrimination. This can be

overt. According to the World Bank, 104

countries still ban women from some pro-

fessions. Russian women, for example,

cannot be ship’s helmsmen (in order, ap-

parently, to protect their reproductive

health). More often discrimination is co-

vert or the unintended consequence of un-

conscious biases.

Countries can also tap older workers.

Ben Franklin, of

ILC UK

, a think-tank, ar-

gues that 65, a common retirement age, is

an arbitrary point at which to cut off a

working life. And in many countries even

gettingworkers to stickarounduntil then is

proving difficult. Today Chinese workers

typically retire between 50 and 60; but by

2050 about 35% of the population are ex-

pected to be over 60. Thanks to generous

early-retirement policies, only 41% of Euro-

peans aged between 60 and 64 are in paid

work. Among 65- to 74-year-olds the pro-

portion is lower than 10%. In Croatia, Hun-

gary and Slovakia it is belowone in 20.

The levers for governments to pull are

well known: they can remove financial in-

centives (tax or benefits) to retire early and

increase those to keepworking. Raising the

state retirement age is a prerequisite almost

everywhere; if the average retirement age

were increased by 2-2.5 years per decade

between 2010 and 2050, this would be

enough to offset demographic changes

faced by “old” countries such as Germany

and Japan, found Andrew Mason of the

University of Hawaii and Ronald Lee of

the University ofCalifornia, Berkeley.

Employers, too, will have to change

their attitudes to older workers. Especially

in Japan and Korea, where they are most

needed, workers are typically pushed out

when they hit 60 (life expectancy is 84 and

82 respectively). Extending working lives

will require investment in continued train-

ing, flexible working arrangements, such

as phased retirement, and improvedwork-

ing conditions, particularly for physically

tough jobs. In 2007

BMW

, a German car-

maker, facing an imminent outflow of ex-

periencedworkers, set up an experimental

older-workers’ assembly line. Ergonomic

tweaks, such as lining floors with wood,

better footwear and rotating workers be-

tween jobs, boosted productivity by 7%,

equalling that of younger workers. Absen-

teeism fell below the factory’s average.

Several of these adjustments turned out to

benefit all employees and are nowapplied

throughout the company.

A final option is to lure more migrants

in their prime years. Working-age popula-

tions are expected to keep growing for de-

cades in countries such as Australia, Cana-

da and New Zealand, which openly court

qualifiedmigrants. Others can try to entice

foreign students and hope they stick

around. Arturas Zukauskas, the rector of

Vilnius University, thinks that he could im-

prove greatly on the current tally of foreign

students—just 700 out of19,200. In particu-

lar, he looks to Israel, which has the highest

birth rate in the richworld. Lithuania had a

large Jewish population before the second

world war, and many prominent Israelis

have roots in the country. Partly to signal

the academy’s openness, Vilnius Universi-

ty has started awarding “memory diplo-

mas”, mostly posthumously, to some Jew-

ish students evicted onNazi orders.

The trouble is that the countries with

the biggest demographic shortfalls are of-

ten the most opposed to immigration. For

example, the inhabitants of the Czech Re-

public and Hungary view immigrants

more negatively than any other Europeans

do, according to the European Social Sur-

vey. Those countries’ working-age popula-

tions are expected to shrink by 4% and 5%

respectively between 2015 and 2020.

Countries that lacka recent historyofmass

immigration may have few supporters for

opening the doors wider. Even if they

wanted new settlers, they might have to

look for them far afield. Countries with

shrinking working-age populations are of-

ten surrounded by others that face the

same problem.

“China has never been a country of im-

migrants,” explains Fei Wang of Renmin

University in Beijing. It is unlikely to be-

come one, but is trying to lure back emi-

grants and to attract members of the eth-

nic-Chinese diaspora. In February the

government relaxed visa laws for “foreign-

ers of Chinese origin”. In Shanghai, and

perhaps soon in other cities, foreign-pass-

port holders are allowed to import maids

from countries such as the Philippines.

That is a small step in the right direction.

Just as countries’ demographic chal-

lenges vary in scale, so the remedies will

help more in some countries than in oth-

ers. Take Italy and Germany. Both have

shrinking working-age populations that

are likely to go on shrinking roughly in par-

allel. But Italy could do far more to help it-

self. Because the women’s employment

rate in Italy lags so far behind the men’s

rate, its active population would jump if

that gap closed quickly—and if everybody

worked longer andbecamemore educated

(see chart 2). Germany coulddo less tohelp

itself, and Lithuania less still.

In theory, every rich country can prise

open the demographic trap. Governments

could begin by lowering barriers to immi-

grants and raising the retirement age. They

could entice more women into the work-

force. They could raise the birth rate bypro-

viding subsidised child care, which would

create a wave of new workers in a couple

ofdecades, justwhen the other reforms are

peteringout. But,whena country is shrink-

ing, many things come to seem more diffi-

cult. Earlier this year, Poland built up a

large backlog of immigration applications,

many of them from Ukrainians. It turned

out that the employment offices were bad-

ly understaffed, and could not process the

paperwork in time. They had tried to take

onworkers, but failed.

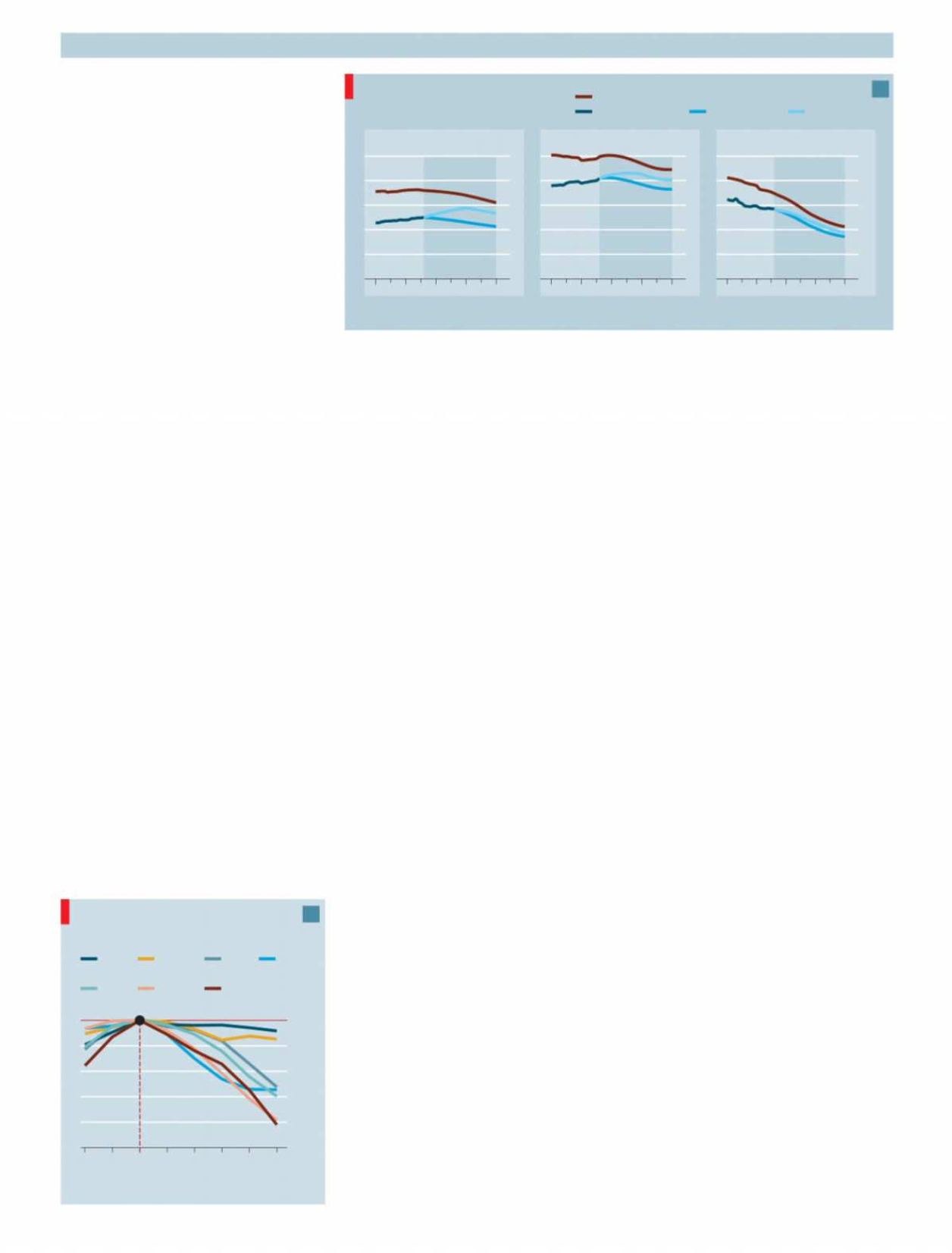

7

1

Sloping off

Source: United Nations Population Division *Aged 15-64

Working-age population*,

(peak year=100)

75

80

85

90

95

100

10 5

Peak

5 10 15 20 25

France

(2010)

Russia

(2010)

China

(2015)

Germany

(1995)

Japan

(1995)

Lithuania

(1990)

Thailand

(2020)

Years before/after peak

2

The Italian jobs

Source: T. Van Rie,

J. Peschner, B. Kromen

*Assumes activity rates by sex, age and education remain constant

†

Assumes female activity rate

reaches male rate by 2030; strong rise in age 55-64 activity rate; rapid educational progress

Working-age population, m

Italy

Germany

Lithuania

Working-age population (aged 20-64)

Active population

Low scenario*

High scenario

†

0

10

20

30

40

50

2000 10 20 30 40

FORECAST

0

10

20

30

40

50

2000 10 20 30 40

FORECAST

0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

2000 10 20 30 40

FORECAST

РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News"

VK.COM/WSNWS