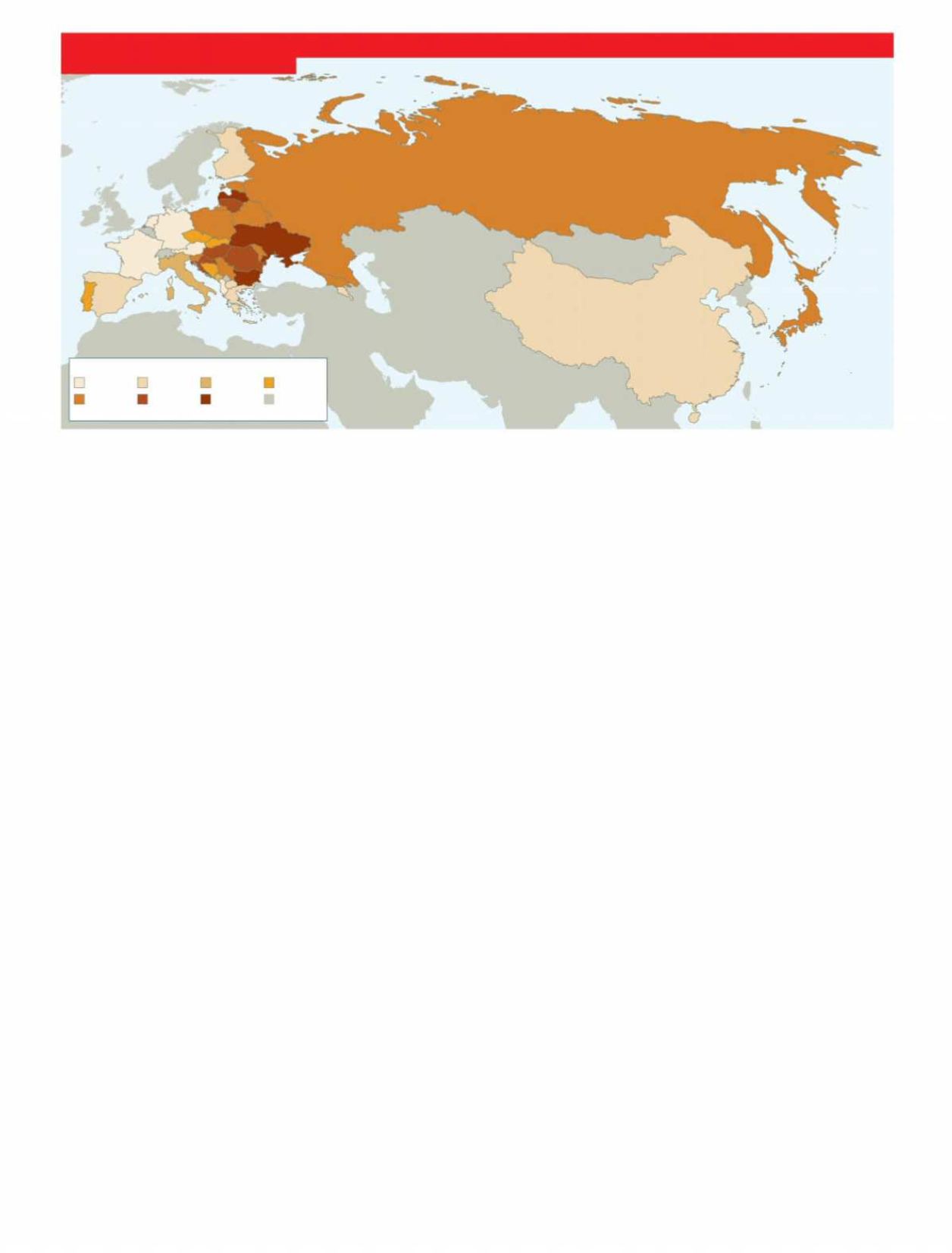

0 to -0.9

-1.0 to -1.9 -2.0 to -2.9 -3.0 to -3.9

-4.0 to -4.9 -5.0 to -5.9 -6.0 to -7.9 Growing

Source: United Nations Population Division

*Aged 15-64

Working-age population*, % change, 2015-20 forecast

The Economist

May 5th 2018

57

1

M

ANY developed countries have anti-

immigration political parties, which

terrify the incumbents and sometimes

break into government. Lithuania is un-

usual in having an anti-emigration party.

The small Baltic country, with a popula-

tion of 2.8m (and falling), voted heavily in

2016 for the LithuanianFarmer andGreens’

Union, which pledged to do something to

stem the outward tide. As with some

promises made elsewhere to cut immigra-

tion, not much has happened as a result.

“Lithuanians are gypsies, like the

Dutch,” says Andrius Francas of the Alli-

ance for Recruitment, a jobs agency in Vil-

nius, the capital. Workers began to drift

away almost as soon as Lithuania declared

independence from the Soviet Union in

1990. The exodus picked up in the newcen-

tury, when Lithuanians became eligible to

worknormally in the

EU

. Formany, Britain

is the promised land. In the Pegasas book-

shop just north oftheNeris river inVilnius,

four shelves are devoted to English-lan-

guage tuition. Noother language—not even

German or Russian—getsmore than one.

Mostly because of emigration, the

number of Lithuanians aged between 15

and 64 fell from 2.5m in 1990 to 2m in 2015.

The country is now being pinched in an-

other way. Because its birth rate crashed in

the early 1990s, few are entering the work-

force. The number of 18-year-olds has

dropped by 33% since 2011. In 2030, if Un-

itedNations projections are correct, Lithua-

nia will have just 1.6m people of working

2020. In1990 therewere just17.

Some countries face gentle downward

slopes; others are on cliff-edges. Both Chi-

na and France are gradually losing work-

ing-age people. But, whereas numbers in

France are expected to fall slowly over the

next few decades, China’s will soon

plunge—a consequence, in part, of its one-

child policy. The number of Chinese 15- to

64-year-olds, which peaked at just over1bn

in 2014, is expected to fall by 19m between

2015 and 2025, by another 68m in the fol-

lowing decade, and by 76m in the one after

that (see chart1on next page).

Jörg Peschner, an economist at the Euro-

pean Commission, says that many coun-

tries face demographic constraints that

they either cannot orwill not see. He hears

much debate about how to divide the eco-

nomic cake—should pensions be made

more or less generous?—and little about

how to prevent the cake from shrinking.

Yet countries are hardlypowerless. Even ig-

noring the mysterious business of raising

existing workers’ productivity, three poli-

cies can greatly alleviate the effects of a

shrinkingworking-age population.

Never done

The first is to encouragemorewomen to do

paid work. University-educated women

of working age outnumber men in all but

three

EU

countries, as well as America and

(among the young) SouthKorea. Yet female

participation in the labour market lags be-

hindmen’s inall but three countriesworld-

wide. Among rich countries, the gap is es-

pecially wide in Greece, Italy, Japan—and

South Korea, where 59% of working-age

womenwork comparedwith 79% ofmen.

Governments can help by mandating

generous parental leave—with a portion

fenced off for fathers—to ensure that wom-

en do not drop out after the birth of a child.

And state elderly care helps keep women

working in their 50s, when parents often

age—back towhere it was in1950.

Lithuania was an early member of a

growing club. Forty countries now have

shrinking working-age populations, de-

fined as 15- to 64-year-olds, up from nine in

the late 1980s. China, Russia and Spain

joined recently; Thailand and Sri Lanka

soon will. You can now drive from Vilnius

to Lisbon (or eastward to Beijing, border

guards permitting) across only countries

with fallingworking-age populations.

It need not always be disastrous for a

country to lose people in their most pro-

ductive years. But it is a problem. A place

with fewer workers must raise productivi-

ty evenmore to keep growing economical-

ly. It will struggle to sustain spending on

public goods such as defence. The national

debt will be borne on fewer shoulders.

Fewer people will be around to come up

with the sort of brilliant ideas that can en-

rich a nation. Businesses might be loth to

invest. In fast-shrinking Japan, even do-

mestic firms focus on foreignmarkets.

The old will weigh more heavily on

society, too. The balance between people

over 65 and those of working age, known

as the old-age dependency ratio, can tip

even in countries where the working-age

population is growing: just look at Austra-

lia or Britain. But it is likely to deteriorate

faster if the ranks of the employable are

thinning. In Japan, where young people

are few and lives are long, demographers

expect there to be 48 people over the age of

65 for every 100 people of working age in

Demography and its consequences

Small isn’t beautiful

VILNIUS

Theworking-age population is already shrinking inmanycountries, and the

declinewill accelerate. But demography is not quite destiny

International

РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News"

VK.COM/WSNWS