The Economist

May 5th 2018

Britain 55

2

Citizenship applications

No sex, please, we’re the Home Office

I

N ITS drive to get net migration below

100,000 per year, the government has

made it drastically harder to gain British

citizenship. The number of foreigners

getting British passports plummeted

from194,370 in 2012 to just123,229 last

year, following a tightening of the rules

for bringing over familymembers and a

steep increase in the cost of applying.

Themost common reason that sub-

missions are rejected, however, is a rather

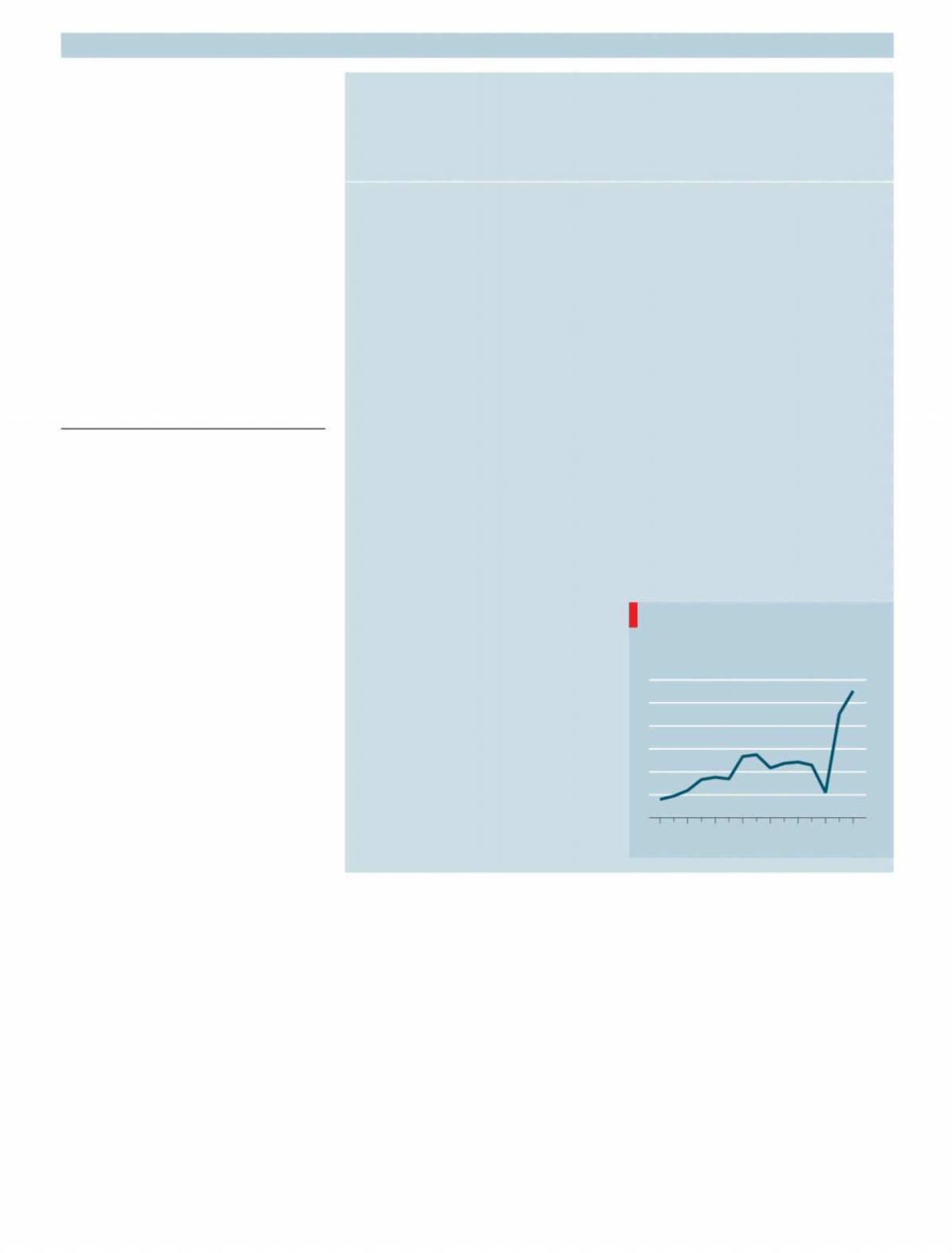

vague one. Since 2012 the number of

applications thrown out under a “good

character” clause has doubled (see chart).

In 2016, themost recent year forwhich

data are available, thiswas the cause of

44% of all refusals.

What constitutes bad character, in the

eyes of the Home Office? Committing

terrorismwill do the trick, official guide-

lines explain. But somight receiving a

police caution, skipping a tax bill or

“recklessly” accruing debt. Immigration

lawyers believemost of the increase in

rejections is down to stricter consider-

ation ofminor offences. In one case, a

Botswananwho had served in the British

army failed the character test because he

had broken the speed limit on amotor-

way (the decisionwas later reversed in

court). Solange Valdez-Symonds, head of

the Project for the Registration of Chil-

dren as British Citizens, an advice service,

reports an increase in youngsters being

turned down because ofminor offences

committed by their parents.

Yet the definition of bad character is

extraordinarily broad. The guidelines list

characteristics that “should not normally,

of themselves, be relevant”, including

drinking, gambling, divorce, promiscuity

and “eccentricity, including beliefs, ap-

pearance and lifestyle”. But, they go on,

somewhat ambiguously, applicantsmay

be rejected if “the scale and persistence

of their behaviour” hasmade them

“notorious in their local or thewider

community”. The Home Officewas

unable to say howmany of the 5,525

people rejected for their character in 2016

were turned down for being persistently

and notoriously promiscuous. Lawyers

say notoriety is very seldom invoked.

Still, for a department under intense

pressure to get migration numbers down,

the vague character clause offers a simple

way to increase rejections. Officials can

turn down a candidate if they have any

unspecified “doubts about their charac-

ter”. For applicants, it canmake the pro-

cess an expensive lottery. And after the

events of recent weeks, manymight

wonderwhether the Home Office, of all

departments, iswell placed to judge

others on their good character.

Promiscuous? Divorced? Eccentric-looking? Youmaybe denied a passport

Out of character

Source: Home Office

Britain, citizenship rejections under

the “good character” clause, ’000

0

2

4

5

3

1

6

2002 04 06 08 10 12 14 16

that led to Britons being shabbily treated.

Still, the retired home secretaries’

chorus has won some converts. William

Hague, a former Tory leader, agrees that

the case for cards is now stronger. “We

Conservatives were against this a decade

ago, but times have moved on,” he wrote

this week. Britain already issues migrants

from outside Europe with

ID

cards in all

but name, andmight do the same for Euro-

peans who stay after Brexit. Some say it

would be fairer for everyone to get them.

Charles Clarke and Mr Johnson were

among those given the cards in 2009. Mr

Johnson still carries his in his wallet. Mr

Clarke used to produce it at airports “just to

prove that I could”. When the scheme was

ditched, “they refused to refund me my

£30, which I thought was tyrannical.” It

could yet prove a long-term investment.

7

W

AITING in a studio for a

TV

inter-

view on April 30th, Mike Coupe, the

boss of Sainsbury’s supermarket, was

caught on camera quietly singing “We’re in

the money” to himself. Having just an-

nounced the biggest deal in the grocery

business for over a decade, it is easy to see

why the tunemight have come tomind.

Nonetheless, hehad toapologisequick-

ly, for fear of appearing rather smug—and

for getting ahead of himself. Sainsbury’s

proposed merger with Asda might boost

the two supermarkets, but the competition

authorities could well rule against it. The

proposed deal is another example of the

unwelcome and increasing concentration

of capitalism in Britain.

Some consolidation in the cut-throat

supermarket business had been expected.

A tie-up between the second-largest store,

Sainsbury’s, and third-largest, Asda,

owned by America’sWalmart, makes a lot

of sense for both parties. Combining mar-

ket shares of 15.9% and 15.5% respectively,

according to Kantar Worldpanel, the new

entity would leapfrog the current market

leader, Tesco, which has 27.6%.

Scale is vital to grocers, giving them

more muscle to negotiate with suppliers.

Sainsbury’s and especially Asda have

beenhit by the success ofAldi and Lidl. Ten

years ago the German discounters had

about 4% of the market. Now they have

nearly 13%. Mr Coupe says the proposed

merger could cut prices across the new

group by 10%. Whether this would be

enough to compete with the discounters

remains to be tested.

Synergies between the two companies

could save £500m ($680m). Sainsbury’s

bought Argos, a home retailer, in 2016 and

would roll out Argos stores inAsda aswell.

Sainsbury’s could exploit Asda’s advanced

logistics systems, while Asda would bene-

fit from Sainsbury’s much stronger pres-

ence online. In that market they face a new

competitor in Amazon, which started sell-

ing groceries in Britain in 2016.

The two firms have got a lot of what it

takes to get along. But competition regula-

tors may feel differently. There are many

places where Sainsbury’s and Asda stores

are close by. Regulators may thus insist on

the sale of one or other. They could even

block the deal altogether.

The deal comes in a context of increas-

ing concentration in many industries. In

the past decade Britain has witnessed

about $2trn-worth of mergers and acquisi-

tions of domestic firms. Our analysis sug-

gests that, relative to the size of the econ-

omy, that is over a fifth more than in

America over the same period. American

economists and politicians are increasing-

ly concerned that their economy has be-

come too concentrated, limiting competi-

tion and eroding consumerwelfare.

Perhaps Britain should worry more,

too. Over the past two decades corporate

profits as a share of

GDP

have been roughly

50%higher than their long-termrate. Profit-

ability, as measured by return on capital, is

also near a historical high. Regulatorsmust

askwhether companies are in themoney a

littlemore than is healthy.

7

Sainsbury’s and Asda merge

In the money

Abig shake-up in the grocerymarket

could be blocked by regulators

РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News"

VK.COM/WSNWS