50 Europe

The Economist

May 5th 2018

2

of the Warsaw ghetto uprising, one might

have thought that tension between Jews

and European nationalists had been put to

rest. Andrzej Duda, Poland’s president,

who hails from the nationalist Law and

Justice (

P

i

S

) party, lauded the suicidal hero-

ismof the Jewish fighterswho battledNazi

troops for nearly a month. Israeli-Polish re-

lations have been in crisis since the

P

i

S

gov-

ernment passed the Holocaust law, which

many Jews consider an attempt to white-

wash history, and the ceremony gave Mr

Duda a chance tomend fences.

But Mr Duda also claimed the Jewish

fighters’ sacrifice as part of Poland’s own

story. “They died fighting for dignity, for

freedom, but also for Poland, because they

were Polish citizens,” he proclaimed. This

touched a sore spot: many Jews feel that

Poland historically did not consider its

Jews to be fully Polish.

Across much of eastern Europe, por-

tions of the population still entertain

doubts on that score, according to Pew fig-

ures. In Lithuania 23% say they would not

be willing to accept Jews as citizens; in Ro-

mania it is 22%, in Poland 18%. This is not

surprising. Historically, eastern Europe has

been the main staging ground of modern

anti-Semitism and genocide, not just dur-

ing the Holocaust but in events such as the

revolt of Bogdan Khmelnitsky, a Cossack

hetman

(military commander) in the 17th

century, and thepogroms oftheBlackHun-

dreds, a Tsarist militia in the 19th century.

Yet curiously, in Ukraine, where the his-

tory of anti-Semitism is as bloody as any-

where, just 5% are unwilling to see Jews as

citizens. UnlikeCatholic Poland, Ukraine is

multi-religious (though mainly Orthodox

Christian) and has a substantial Jewish

population, of around 300,000. Vyaches-

lav Likhachev, a sociologist who monitors

anti-Semitism, says that apart from a fad

for neo-Nazi youth subculture a decade

ago, it has not really caught on. Radical-

right parties with anti-Semitic ideologies

have rarely won more than 1% of the vote.

More recently, he points out, “because of

Russian aggression they have a real enemy.

Theydon’t need conspiracy theories about

the Zionist OccupationGovernment.”

Indeed, in most countries, anti-Semi-

tism rises or falls in concert with national-

ism and identity politics. David Feldman

of the Pears Institute notes the importance

of “competitive victimhood”, in which

claims ofoppressionby Jews,Muslims and

other groups step on each others’ toes. Da-

riusz Stola, head of the Polin Museum of

Polish Jewish History, says the same is true

in Poland, where the national story is one

of victimisation byGermany and Russia. It

ismore accurate, he thinks, to see anti-Sem-

itism as part of a general wave of chauvin-

ist sentiment since the migrant crisis of

2015; levels of hostility to Muslims, gays

and Roma have risen too. Says Mr Stola:

“Xenophobia is not selective.”

7

I

TLOOKSmore like a carnival than a revo-

lution. Instead of burning tyres and

mounting barricades, young people wrap

themselves inArmenianflags, dance in the

streets and block the roads by playing vol-

leyball or simply sitting on carpets. On the

morning of a general strike, a five-year-old

boy drove a toy car with an Armenian flag

through an empty street. In the evening,

vast construction trucks loaded with stu-

dents drove and hooted through Yerevan.

But behind the street theatre lies a vel-

vet revolution ledbya younggenerationof

Armenians against an old guardwho have

controlled the country since its indepen-

dence in 1991. Their victory is not yet com-

plete, but their anticipation of success

seems likely to be self-fulfilling. On May

1st, in an attempt to hold out, the ruling

party blocked the election as prime minis-

ter by parliament of Nikol Pashinian, the

leader of a three-week-old protest that has

galvanised the entire former Soviet repub-

licofsome 3mpeople. Adozenpro-govern-

ment

MP

s desperately tried to discredit

him as a dangerous anti-Russia candidate,

unacceptable to the Kremlin, which has a

tight economic and military grip over Ar-

menia. But Moscow was silent, confident

of its strategic hold on Armenia and un-

willing to back the losing side.

That evening Mr Pashinian addressed

tens of thousands of people who filled in

the main Republic square. “Beloved na-

tion, proud citizens of Armenia. People in

parliament have lost the sense of reality.

They don’t understand that 250,000 peo-

ple who came onto the streets in Armenia

have already won. Power in Armenia be-

longs to you—and not to them.” His words

sparked jubilation. To prove his point and

his strength, Mr Pashinian called a general

strike paralysing the city and the country.

A few hours later, on May 2nd, the rul-

ing party appeared to cave in, implying it

would backhim in next week’s parliamen-

tary session. It may still spring a nasty sur-

prise, but is unlikely to regain control over

the country—at least not for now. Mr Pashi-

nian has led a textbook velvet revolution,

made possible by textbookmistakes by the

government, which tried to hang onto

power after losing its legitimacy.

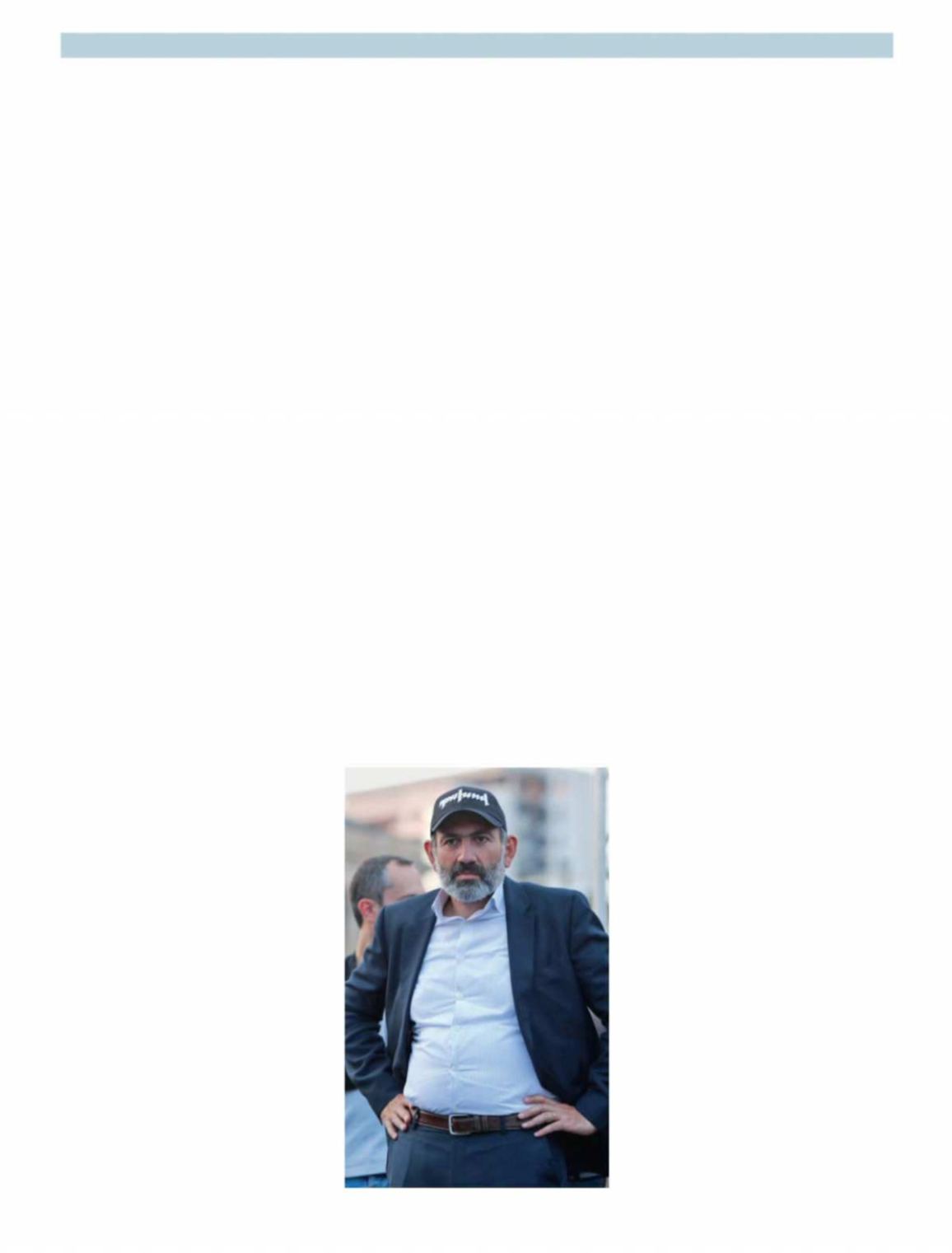

Mr Pashinianmanaged to personifyAr-

menians’ resentment against a corrupt

elite. Donning Che Guevara-style fatigues,

he went around the country on foot,

preaching non-violent protest. By doing so,

he decentralised the revolution, making it

virtually impossible for the authorities to

quash. In the capital he appealed to stu-

dents and young people with no memo-

ries of the Soviet past, but a strong sense of

dignity and justice. Mr Pashinian’s brief

detentiondoubled the size ofthe crowds in

the streets, leading the primeminister to re-

sign last week and perhaps making Mr

Pashinian unstoppable.

Crucially, the challenger avoided any

subject such as ideology or geopolitics that

could divide the country and antagonise

Russia. Unlike the revolutions in Georgia

in 2003 and in Ukraine in 2004 and again

in 2014, which were fought under the slo-

gans of joining Europe and

NATO

, Mr Pash-

inian talked strictly about internal matters

like corruption and justice, which every-

one can agree on. He made populist prom-

ises and pledged that Armeniawill remain

with Russia’s security arrangements. Not a

single European flagwaswaved inYerevan

and no slogan pronounced Armenia’s

European destiny. But the fear of mention-

ing Russia-related subjects only highlight-

ed Russia’s importance.

While Moscow clearly distrusts revolu-

tionaries, it has so far decided not to inter-

fere in Armenia, hoping that inflated ex-

pectations and lack ofmoney will do their

own damage. “It has been the smartest

Kremlin policy I’ve seen for years,” says

Alexander Iskandaryan, the head of the

Caucasus Institute, a think-tank. Armen

Grigoryan, one of the revolution’s leaders

says, “All the stars were aligned, and even

Saturn moved into the same position it

was in1988.” Thatwaswhen protests inAr-

menia provided the first rumblings of the

storm that was to bring down the Soviet

empire three years later.

7

Armenia

Velvet revolution,

so far

YEREVAN

Russiawisely stays out of the revolution

Pashinian for PM?

РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News"

VK.COM/WSNWS