48 Middle East and Africa

The Economist

May 5th 2018

L

OCAL lore holds that seven visits to Kair-

ouan’s imposing grand mosque are

equal to the

haj

, the pilgrimage to Mecca

that is one of the “pillars of Islam”. The city

has been a centre of Sunni scholarship for

centuries. Lately, though, it has acquired

another landmark: the “road of death”, a

rutted highway that slices south-west into

the desert. The transport ministry prom-

ised to fix it in 2016 after 27 people died in

wrecks the previous year. Yet the moniker

still fits. On April 18th a pregnant woman

was seriously hurt in a crash. She might

have lived if the local hospital used para-

medics qualified to operate the ambu-

lance. Instead, she died hours later.

Since their revolution in 2011, Tunisians

have been stuck with unelected local gov-

ernments that do little to fix up highways

and hospitals. That is meant to change on

May 6th, when voters choose municipal

councils for the first time. The elections,

originally scheduled for 2016, have been

postponed four times. They come asmany

Tunisians are growing frustrated with de-

mocracy, which has not yet brought pros-

perity. Candidates have focused on local

grievances. But the campaign has led to a

wider debate about the imbalance of pow-

er and resources in Tunisia.

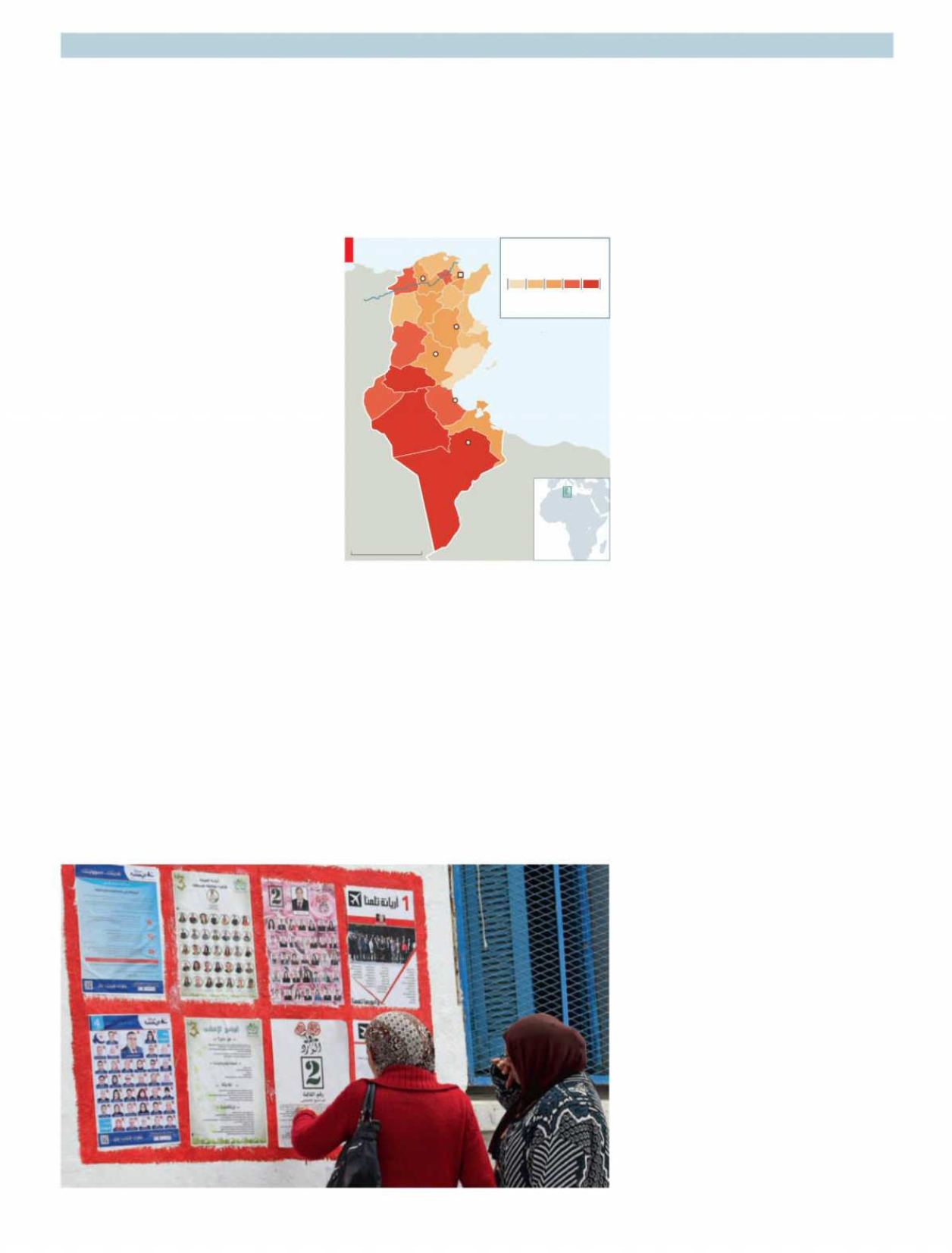

Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, the deposed

dictator, steered most of Tunisia’s riches to

the northern coast. It got 82% of develop-

ment funds in his final budget. The south

and west lag on almost every socioeco-

nomic indicator. Though the interior con-

tainsmuchofTunisia’s farmland, itsminer-

al resources and some of its best tourist

attractions, it reaps few benefits. Ta-

taouine, in the south, is the hub ofTunisia’s

oil industry. But profits are whisked up

north. The governorate has the country’s

highest unemployment rate. “The revolu-

tion was supposed to address this imbal-

ance,” says RachidGhannouchi, the leader

ofEnnahda, an Islamist party that is part of

the governing coalition.

Ennahda is the front-runner in the local

elections. It has deep roots in rural areas

and was the only party to field lists in all

350 districts. But both it and Nidaa Tounes,

a secular party that leads the government,

have lost some of their shine. They have

struggled to kickstart the economy. The un-

employment rate is over 15% nationally

and higher in the countryside, leading to

despair. At least 33 people have tried to kill

themselves this year in Sidi Bouzid, an im-

poverished region of around 430,000 peo-

plewhere the Arab spring began.

The politicians in Tunis appear out of

touch. They have granted amnesty to cor-

rupt officials and refused to extend the

termof a commission investigating abuses

by the old regime. But the municipal elec-

tions have brought a surge ofpolitical new-

comers. Thousands of young people are

running, many as independents.

In Beja, a town ofwhitewashed houses

in the western hills, the candidates talk

about water. The region is Tunisia’s bread-

basket. It has the country’s largest dam,

which tames the Medjerda river. For the

past three years, though, water has been

scarce. Shortages last summer left some

villages dry for days at a time. Just 72% of

homes in the surrounding province are

connected to the national water grid, com-

pared with 90% in the capital, according to

the 2014 census. Candidates promise to up-

grade the infrastructure and improve wa-

ter distributionwhen droughts hit.

Campaigning is also in full swing inGa-

bes, a city best known for two things. One

is the world’s only seaside oasis. The other

is a phosphate plant that belches pollution

into the sky. The fumes have contributed to

the deaths of hundreds of trees—and hun-

dreds of people. Candidates from all par-

ties say they will enforce environmental

laws and stop the urban sprawl that threat-

ens to overrun the oasis.

This all looks promising: diverse cam-

paigns focused on local issues. The fear is

that these promises will go unfulfilled. For

decades local officials were unable to do

anything without approval from the capi-

tal. Days before the election, parliament

passed a long-debated law that grants

themgreater autonomy. But implementing

it will require a major change from Tuni-

sia’s notoriously centralised bureaucracy.

Even with a wider mandate, the councils

will have limited resources. Tunisia allo-

cates just 4%ofits budget tomunicipalities,

compared with 10% in nearby Morocco, a

richer country.

There are also signs the election will be

a damp squib. Polls suggest that barely one

in five Tunisians plans to vote (compared

with nearly 70% in the most recent parlia-

mentary election). This is the first election

in which soldiers and police officers may

cast ballots. They did so on April 29th,

since they will be deployed on election

day. Turnout was just 12%. In the capital,

some politicians fear the vote will only

cause more anger—directed at them. “We

should postpone local governance,” says

MohsenMarzouk, the leader ofMachrouu

Tounes, a secular party. “With what we

have now, we can only sharemisery.”

7

Local democracy in Tunisia

A road to nowhere?

BEJA AND KAIROUAN

The uncertain promise ofmunicipal elections inTunisia

A L G E R I A

TUNISIA

L I B Y A

Kairouan

Sidi Bouzid

Gabes

Tataouine

Beja

Tunis

Mediterranean Sea

10 15 20 25 >25

5

Source: National Institute

of Statistics

Unemployment rate

By governorate, 2016, %

200 km

M

e

d

j

e

r

d

a

At least we have a choice now

РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News"

VK.COM/WSNWS