The Economist

May 5th 2018

45

For daily analysis and debate on the Middle East

and Africa, visit

Economist.com/world/middle-east-africa1

F

EWpresidents have entered office amid

such low public expectations as did

João Lourenço, who in September became

Angola’s first newpresident in 38years. His

assumption of power did not involve a

change of ruling parties. Rather, hewas the

handpicked successor of José Eduardo dos

Santos, who had run the country since

1979, and whose cronies controlled much

of the economy. His daughter, Isabel, ran

the national oil company, Sonangol, by far

the country’sbiggest source ofhard curren-

cy. His son, José Filomeno, ran the $5bn

sovereignwealth fund. Even in retirement,

Mr dos Santos kept his role as leader of the

ruling party. Everyone assumed that he

wouldwield power behind the scenes.

Yet since being sworn in, the soft-spo-

ken Mr Lourenço has unleashed change

that seemed unthinkable a year ago. As

well as trying to revive an economy bat-

tered by low oil prices (which have re-

bounded), he has mounted a spirited anti-

corruption campaign. He is also steadily

prising the fingers of the dos Santos clan

from the levers of power.

Both Isabel and José Filomeno have

been sacked. José junior faces fraud char-

ges (which he denies) over an alleged at-

tempt to transfer $500m from the fund

through an account in London. The former

president’s allies are in the cross-hairs, too.

Mr Lourenço has fired the chief of staff of

the armed forces (who is also under inves-

tigation for fraud), as well as the head of

currency, the kwanza, from the dollar,

prompting it to fall by 27% since January.

And he has made the country more entic-

ing to foreign investors by lifting a law that

had required them to have local partners

whoownedabout a thirdoftheirbusiness.

He is also trying to breakup statemonopo-

lies, which exist mostly to waste petrodol-

lars, and has asked the

IMF

for advice.

He certainly needs it. Angola’s govern-

ment is drowning in debt, which is about

65% of

GDP

(see chart) and rising. Manuel

Alves da Rocha, an economist at the Cath-

olic University of Angola, reckons the cost

of servicing public borrowing has in-

creased five-and-a-half times since 2014.

Opposition parties are calling for an inde-

pendent audit of the country’s public debt.

They want to know how the government

squandered so much of the hundreds of

billions of dollars it earned fromoil and di-

amonds over the past fewdecades.

Angolans are used to the powerful

growing unfathomably wealthy while the

masses forage for scraps. Although the

mean income per person is $3,110, twice

the sub-Saharan average, about two-thirds

of Angolans subsist on less than $2 a day.

Child and maternal mortality rates are

among theworld’s highest, with about one

child in five dying before the age of five.

In Cazenga, a shantytown in the capi-

tal, residents recentlymarched down fetid,

flooded streets in protest against their liv-

ing conditions. On Independence Square,

demonstrators demanded that public

money held abroad be returned to state

coffers, decrying Mr Lourenço’s offer of

amnesty to thosewho took it. Such dissent

would have been crushed by Mr dos San-

tos. Still, his apparatus of oppression lin-

gers. RafaelMarques deMorais,who inves-

tigates graft, is one oftwo journalists facing

jail for their reporting.

Public anger may affect voting in Ango-

foreign intelligence. The ruling party is ex-

pected to ditch the senior Mr dos Santos at

a congress in September. Newspapers

have swung from sycophantic coverage of

the former first family to decrying them.

Yet the question many are asking is

whether Mr Lourenço, a former defence

minister, is sincerely trying to clean up the

country or just showing who is in charge.

“We don’t know whether he is a real re-

formist,” says Carlos Rosado de Carvalho

of

Expansão

, a business newspaper. “We

don’t knowhimwell enough.”

There are some hopeful signs. Mr Lou-

renço vows to make Angola less nightmar-

ish for investors. Currently theWorld Bank

rates it a harder place to do business than

Syria. Mr Lourenço has unpeggedAngola’s

Angola

How far will João Lourenço go?

LUANDA

Hopes growfor a corruption-wearycountryas a newleader consolidates power

Middle East and Africa

Also in this section

46 Mozambique, still in a hole

46 Can Eritrea and Ethiopia make peace?

47 The end of Yarmouk

47 Lebanon’s snap-happy campaign

48 Local elections in Tunisia

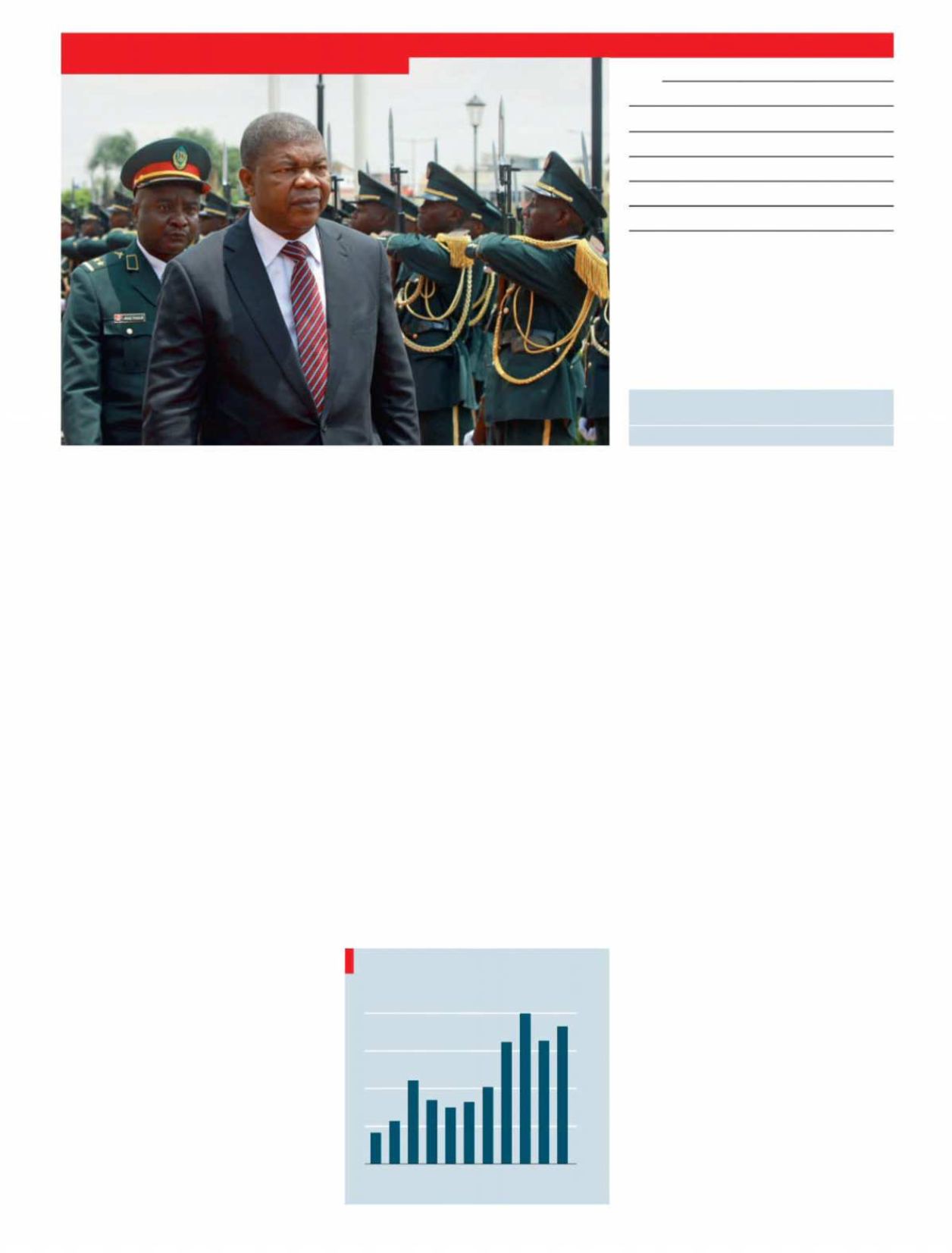

Into thin air

Source: IMF

*Forecast

Angola, gross national debt as % of GDP

0

20

40

60

80

200809 10 11 12 13 14

15 16 17 18*

РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News"

VK.COM/WSNWS