42 China

The Economist

May 5th 2018

1

2

willing to stay in the dirtiest jobs, is not fru-

gal enough to save money to send home

andnot able to earn enough tobuild amar-

ried life.” Its members are less stoical and

unwilling to suffer in silence.

Young migrants share four characteris-

tics that worry the party. Like their parents,

they are not well educated. The men face

more of a “marriage squeeze” than their fa-

thers did, ie, a shortage of women of mar-

riageable age from similar backgrounds.

They similarly earn lowwages and face of-

ficial discrimination as a result of the

hu-

kou

system that shuts many of themout of

subsidised urban services such as educa-

tion and health care. But they are more dis-

satisfied and pessimistic than their parents

were. Their hopes ofcarving out a future in

big cities are being wrecked by high living

costs, demographic change and the hostil-

ity of local governments.

In September 2017 a study in another

Chinese journal,

Sociological Studies

, by

Tian Feng of the Chinese Academy of So-

cial Sciences (

CASS

), tooka detailed look at

the newmigrants. Toflesh it out,

The Econo-

mist

conducted its own (admittedly unsci-

entific) poll of 90 migrants between the

ages of 18 and 33 in six areas of Beijing and

Guangzhou, a large southern city. Com-

bined with earlier studies, these surveys

build up a detailed portrait ofa slice ofChi-

nese society roiled by change.

Mr Tian’s study is based on five surveys

of social conditions, conducted by

CASS

between 2006 and 2015. It shows that mi-

grants born in the 1960s and 1970s had ten

or fewer years of formal education, but

those born after 1980 had 12 or more years.

While the quantity of education received

by thenewgeneration ishigher, the quality

is not. The

hukou

system makes it difficult

for many migrants in the biggest cities to

secure places for their children in state-run

schools, so they send them to ramshackle

private ones that are often forced to close.

A study from 2010 found that only 17% of

migrants with children in such schools in

Beijing thought their offspringwere getting

a good education. Matters have not im-

proved. A cleaner in Beijingwho sends her

son to a private kindergarten told

The Econ-

omist

that “the quality of education is

nothing like as good as in state schools.”

Many members of the new generation

were educated in villages, separate from

their migrant parents who worked in the

cities. A study by the SecondMilitaryMed-

ical University of Shanghai found that

such children did worse than average aca-

demically and were more likely to be de-

pressed. Despite such problems, manypar-

ents feel they have no choice but to leave

their children in the care of relatives in the

countryside. “I haven’t thought about

bringing my kid here,” says a cook in Bei-

jing, “because I can’t afford to.”

The younger generation are products of

China’s one-child policy, which went into

force nationwide in 1980 (although in the

countryside, families were sometimes al-

lowed two). Theyare among the first to suf-

fer its unintended consequences. The one-

childpolicy contributed to a drastic change

in the sex ratio because female fetuses

were aborted byparentswhowanted their

only child to be a boy. The ratio of boys to

girls at birth soared in the 1980s, peaking in

2005, when there were 122 baby boys for

every 100 baby girls, one of the most dis-

torted ratios ever seen.

The average age of first marriage in Chi-

na is 26. The first of the new-generationmi-

grants are reaching that age. Already, the

marriage chances of migrant men are fall-

ing. Wang Chunguang, another scholar at

CASS

, found that three-quarters of the

new-generation migrants he studied were

unmarried. The group he looked at includ-

ed some 18- to 25-year-olds, who may have

been single because they were too young

(in China, womenmust be at least 20 to get

married and men at least 22). But that does

not fully explain the low overall rate. In

The Economist

’s sample, two-thirds of mi-

grants were unmarried. Only two said

they had anywedding plans. A 25-year-old

manager of a food company in Beijing ad-

mitted, “I would need to have a much bet-

ter-paid job or promotion before thinking

about getting a girlfriend.”

The marriage squeeze is about to tight-

en. By 2020, the government says, there

will be 30mmoremen ofmarriageable age

thanwomen: sixbrides for seven brothers,

in effect. Young migrant men will suffer all

the more because of a preference among

Chinese women for marrying men with

more money or education (a practice

known as hypergamy). According to Yue

Qian of Ohio State University, 55% of col-

lege-educated Chinese men marry some-

onewith less education, whereas only 32%

of university-educated women do the

same. Hypergamy happens at every level

of society. As a result, two groups find it

hard to get spouses: women with a lot of

education (known derisively as

sheng nu

,

or left-behindwomen), andmenwithonly

a little schooling. Young male migrants

usually belong in the second category.

Nowheels, no deal

AmongChinesemen generally, a common

response to the shortage of women is for

prospective grooms to buy an apartment

and car before marriage—a sort of reverse

dowry. One survey found that three-quar-

ters of young women in big cities took this

into account before acceptingaman’s offer.

Alas formigrant swains, they cannot afford

such a bride price, especially in expensive

cities such as Beijing and Guangzhou. It is

usually difficult for people without a city’s

hukou

to buy government-subsidised

housing there. Young migrants are there-

fore at a threefold disadvantage. There are

fewer women of marriageable age. Those

who come from their own background

tend to marry richer rivals. And the men

cannot compete in the marriage market by

buying property.

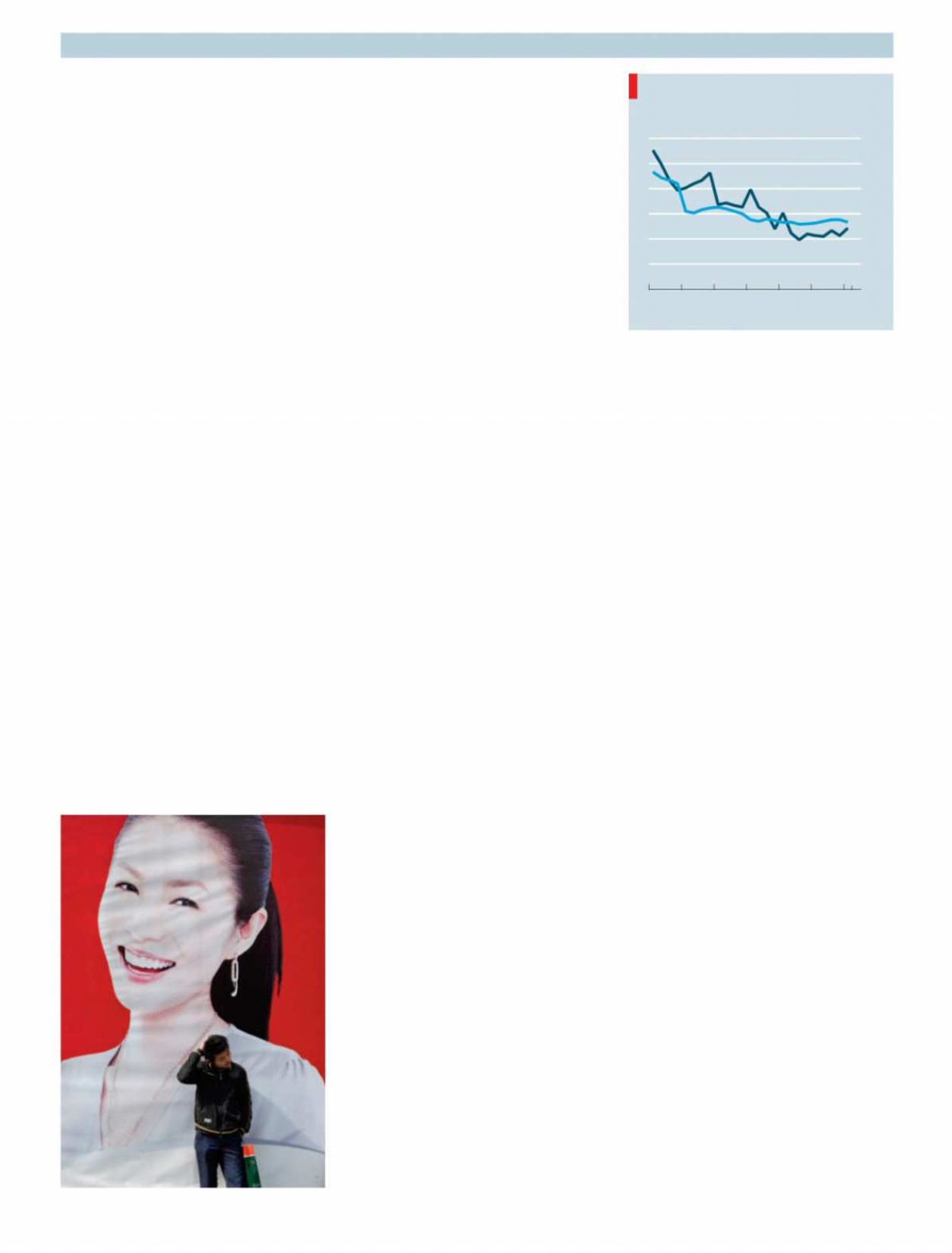

Another problem is income. Rural peo-

plemigrate to cities formoney, and usually

get far more of it than they would if they

had not moved. Migrants’ wages rose from

around 1,700 yuan ($205) a month in 2000

to over 3,000 yuan in 2016. But the rate of

increase fell from almost 17% a year at the

start of 2012 to about 7% at the beginning of

this year. Since 2015, their incomes have

been rising more slowly than those of ur-

ban residents generally (see chart).

The earnings of the youngest ones have

deteriorated the most. Mr Tian looked at

earnings by age. He found that the highest

earners are those in their mid-30s (be-

tween 32 and 36). That remained constant

in all his surveys. But there was a signifi-

cant change among workers in their

mid-20s (22 to 26). In 2008 these younger

migrants were earning almost as much as

the best-paid. By 2015, they were earning

much less.

Thismay be connectedwith changes in

Labour pains

Source: Wind Info

China, % increase on a year earlier

2012 13 14 15 16 17 18

0

3

6

9

12

15

18

Migrant workers

Monthly income

Urban residents

Disposable income

per person

Not much to smile about

РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News"

VK.COM/WSNWS