The Economist

May 5th 2018

China 43

2

the nature ofmigrants’ work, caused by an

economic transformation that is making

China’s growth more reliant on services

and less on manufacturing. The earlier mi-

grants typically found jobs in construction

or on production lines. According to Mr

Tian, 60% of migrants in 2008 worked in

such “secondary industry” sectors. That

share fell to 52% by 2015. Meanwhile, de-

mand for migrants’ labour in the “tertiary

sector”, ie, in services, has taken off. For the

lesswell-educated this often involves inse-

cure work in areas such as food delivery

and cleaning.

The best-laid plans ofmigrants...

One result of this shift into shorter-term or

part-timeworkhas beena fall in savings. In

the past almost all migrants used to save a

third or more of their income to send back

to their villages. But in

The Economist

’s

sample a third of respondents saved noth-

ing. Most youngermigrants “will not make

the sacrifices of frugality in order to save

money”, harrumphs

CASS

’sMrWang. “It is

a far cry from their parents’ generation.”

The upshot is that the new generation

appears to be one of the most dissatisfied

segments of Chinese society. Because the

country has no reliable opinion polls, this

judgment must be tentative. But a proxy

measure, the way people view their own

achievements, suggests it is accurate.

Mr Tian’s survey includes a question

about where respondents place them-

selves in society on a scale from top to bot-

tom. Between 2006 and 2015 the migrants

he questioned gave, on average, ever lower

assessments oftheir social position. Initial-

ly, the younger ones (aged between 22 and

26) were the most likely to describe them-

selves as being in the top halfof society. By

2015 they were more inclined than older

migrants to put themselves in the bottom

half. Mr Tian concludes that those born in

the 1990s are the most disappointed of the

migrants he has studied.

The Economist

’s survey bears him out.

Most migrants want to stay in the big city

but few feel welcome there. “There is no

sense of belonging,” complains a 24-year-

old coffee-shop waiter in Beijing. “For the

moment I will stay,” says a 28-year-old

hairstylist who also lives in the capital,

“but there’s no sense of happiness.”

...gang aft agley

In some ways, little has changed. Most of

the early migrants, concluded the

Journal

of EconomicResearch

nine years ago “knew

they were just passers-by in cities. They

came from rural areas andwere fated to re-

turn there.” But the new generation feels

alienated from the countryside even as

high living costs, the

hukou

system and so-

cial discrimination in the cities “crush their

urban dreams” as well. “They are truly

marginalised people,” it said.

How serious a threat to social stability

are they? They seem unlikely to challenge

the party itself (a surprising one in eight of

those surveyed by

The Economist

said they

were members of it). It is true that some of

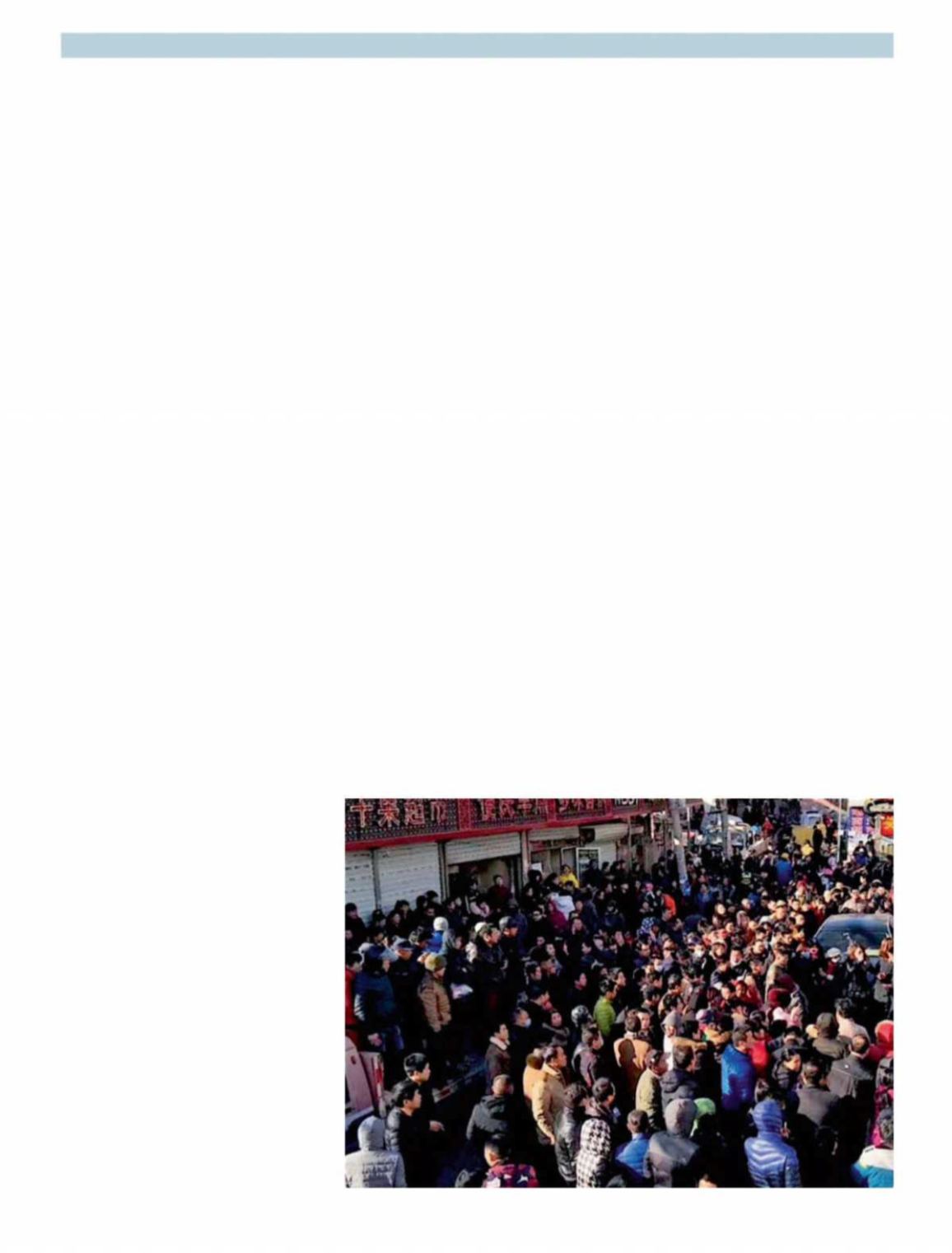

those evicted last winter in Beijing prot-

ested loudly. One group (pictured) chanted

about human rights outside a local-gov-

ernment building. By and large, though,

these are exceptions.Mostmigrants are not

politically active. Few of those who spoke

to

The Economist

werewilling to talkabout

politics. Those who did mostly said they

supported the president, Xi Jinping, be-

cause of his anti-corruption campaign.

The party, however, cannot take their

passivity for granted. Throughout Chinese

history, opposition has seemed muted

right up to the point when it has exploded.

Yu Jianrong of

CASS

wrote in 2014 that the

social exclusion felt by new-generationmi-

grants could forge a sense of common po-

litical cause among them that could even

lead to revolution. Mr Yu called this a “co-

lossal hidden threat to China’s future so-

cial stability”. There is little sign of that yet,

but there are several reasons for thinking

migrantsmight becomemore restless.

As themarriage squeeze tightens, it will

produce a generation of unmarried mi-

grant men with low incomes, poor educa-

tion and no tie to the social order that mar-

riage provides in China. It is a recipe for

discontent. Mr Tian worries about a vi-

cious cycle developing, with poor educa-

tion leading to low income that results in

anti-social attitudes and disruption to chil-

dren’s schooling.

Migrants form a huge group, roughly as

numerous as the middle class. But com-

pared with the middle class, they have lit-

tle to lose and less to keep them loyal to the

party. They revel in subcultures that the

party dislikes. Chinese rap music has its

roots among young migrants, who were

also the main users of Neihan Duanzi, a

popular app specialising in bawdy jokes

that state censors closed down in April.

There are signs that some young migrants

are starting to organise themselves. Strikes

over pay and conditions have become

more common. In April a court in Tong-

zhou, a district of Beijing (next to the area

where the forced evictions tookplace), said

32% of the labour disputes referred to it in-

volved collective agreements, almost dou-

ble the proportion in 2016. This suggested

there was a link between the number of

disputes and the expulsion ofmigrants.

The biggest uncertainty is what will

happen if the economy falters. The party

does not seem ready for this. The social-

safety net is threadbare. The

hukou

regime

means migrants cannot get full access to it

anyway. Modernisers want to reform the

systemand allowmigrants to live more se-

curely in cities. But change has been slow

and patchy. (InGuangzhou only two of the

40 respondents to

The Economist

’s survey

had a local

hukou

.) The government is try-

ing to cap the size of giant cities by pushing

migrants out. Charles Parton of the Royal

United Services Institute, a think-tank in

London, says young migrants will not

overthrow the party, but if the economy

stagnates “they will cause a lot more trou-

ble than they do now.”

The new generation is entering a diffi-

cult period. Itsmenwill remain unmarried

and its children will often be educated

away from home. Many will be on low, in-

secure wages. If the evictions in Beijing are

any guide, the party’s reaction to any dis-

content is likely to be greater repression.

That would make solving migrants’ deep-

seated problems harder, and an explosion

of ragemore likely.

7

“Low-end people” object to being evicted

РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News"

VK.COM/WSNWS