The Economist

May 5th 2018

41

1

W

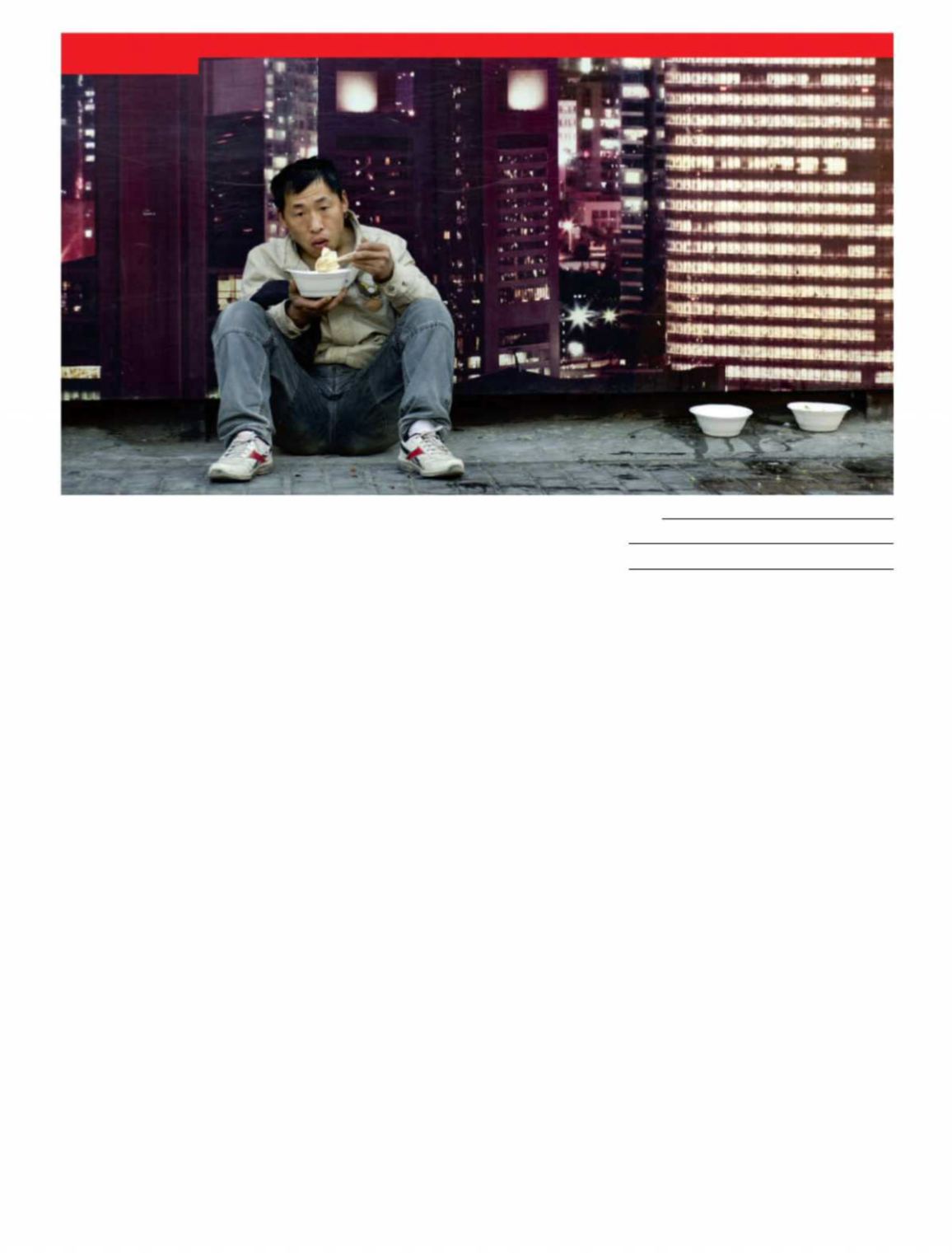

ANG FENG is a 28-year-old cook in

Beijing. But he was not born in the

capital so, under China’s household-regis-

tration (

hukou

) rules, he is not treated as an

official resident, even though he and his

wife work there and have a four-year-old

daughter. One freezing night last Novem-

ber, he returned home to discover that the

city government had declared many of

their area’s tenement blocks unfit for resi-

dential use and had given the inhabitants

24 hours to get out.

The event quickly became notorious.

The overnight eviction of Beijing’s “low-

end population” (a term used in official

planningdocuments issuedby some ofthe

city’s districts) attracted worldwide con-

demnation. Queues of young families

snaked away from the condemned blocks,

heading back to the towns and villages

where they were born. But Mr Wang (a

pseudonym) and hiswife balked at return-

ing without jobs to a village where they

had neither the experience nor the desire

to farm. Instead they headed to another

part of Beijing to start over again. He says

his monthly rent is now far higher: “I can’t

save anything. But at least I have a job and

will stay as long as I can.” If he leaves, he

says, it will be because he wants to, not be-

cause the government has told him to go.

Mr Wang belongs to a new generation

intensive jobs, first in towns and later in cit-

ies. Their cumulative numbers reached

280m in 2017 (the rate ofgrowth is nowtail-

ing off). In 2010 party documents began re-

ferring to a “new generation of migrants”:

those born since 1980. Some are offspring

of earlier migrants and have lived in cities

all their lives. Others have left the country-

side in the past decade. This group has

more than 90mmembers.

The two generations are very different.

Many of the early migrants were born at a

time of mass starvation and were raised

during the chaos of the Cultural Revolu-

tion (1966-76). Theirdetermination tomake

good in the cities was intensified by child-

hood memories of poverty and suffering.

And if they did not succeed, at least they

still had land in the countryside and expe-

rience of farming so they could return to

scratch a living in the fields.

Aiming high

Members of the younger generation are

children ofDeng’s reforms. Theyhave nev-

er worked the land. A study published in

2009 in the Beijing-based

Economic Re-

search Journal

said the younger migrants

wanted “personal development”, unlike

their parents who were focused on more

basic needs. The new generation, it con-

cluded rather snobbishly, “is no longer

of people from the countryside who have

moved to work in cities. Over the past 40

years, hundreds ofmillions have done this,

providing the blood, sweat and tears of

China’s economic miracle. The Commu-

nist Party has often congratulated itself

that such a vast movement of people has

happened without mass unrest. But those

such as MrWang who have left rural areas

more recently challenge the party’s sense

of security. They face a wider range of pro-

blems than earlier participants in the rural

exodus. They are dissatisfied with their lot

and have little to lose. Theymay prove less

quiescent than their predecessors.

When observers of China think of

threats to the party, they often focus on the

rapid growth of the country’s newmiddle

class. At some point, surely, China’s

wealthier millions will demand a more

open, accountable and even democratic

government, just asmiddle classes inother

countries have done. But many Chinese

analystsworry less about the kind of insta-

bility that occurred during the student-led

protests of1989. Rather, they fret about tur-

moil createdbymembers ofa social under-

class: poor workers in the cities whose

family ties are rural.

After1978, when Deng Xiaoping started

to open up the economy, huge numbers of

farmers began flocking to fill new labour-

Internal migrants

The bitter generation

BEIJING AND GUANGZHOU

Angryyoung city folkwith rural backgrounds threaten social stability

China

Also in this section

44 Banyan: The Sino-US tech tussle

РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News"

VK.COM/WSNWS