The Economist

May 5th 2018

Asia 39

2

tion vote in

BN

’s favour. The government

may also be boosted by wrangling within

PH

. Anwar Ibrahim, a

PH

leader nowin pri-

son on flimsy evidence for sodomy, once

led the opposition to Dr Mahathir, who

had him jailed. Disagreements between

such newalliesmay hamstring

PH

.

The tricks and traps of the electoral sys-

tem disgust many Malaysians. Youngsters

are particularly appalled by the dirty

horse-trading. Both sides are trying hard to

woo them, for the simple reason that Ma-

laysians aged between 21 and 40 make up

more than two in five of the almost15meli-

gible to vote. “Rebranding is a must for

UMNO

,” admits Azril Sarit, a youth chief

for the party in the state of Pahang. A

PH

counterpart in Johor says he arranges talks

in 24-hour eateries andonFacebookLive to

bring young people over to Dr Mahathir’s

side. “Only we can provide a new alterna-

tive to theMalays,” he reckons.

Turnout may be crucial. Dr Mahathir

reckons that if 80% vote, that could tip the

contest in favourofhis

PH

coalition. But the

short campaign and a mid-week election

may discourage a surge to the polls. Last-

minute legal, bureaucratic or logistical ob-

staclesmayyet hurt his lot. So could irregu-

larities at polling stations. Salleh Said Ke-

ruak,

the government minister for

communications, says Dr Mahathir is

warning of foul play only because he

knows he will lose. But the government’s

devious election ploys suggest failure may

have crossedMr Najib’smind too.

7

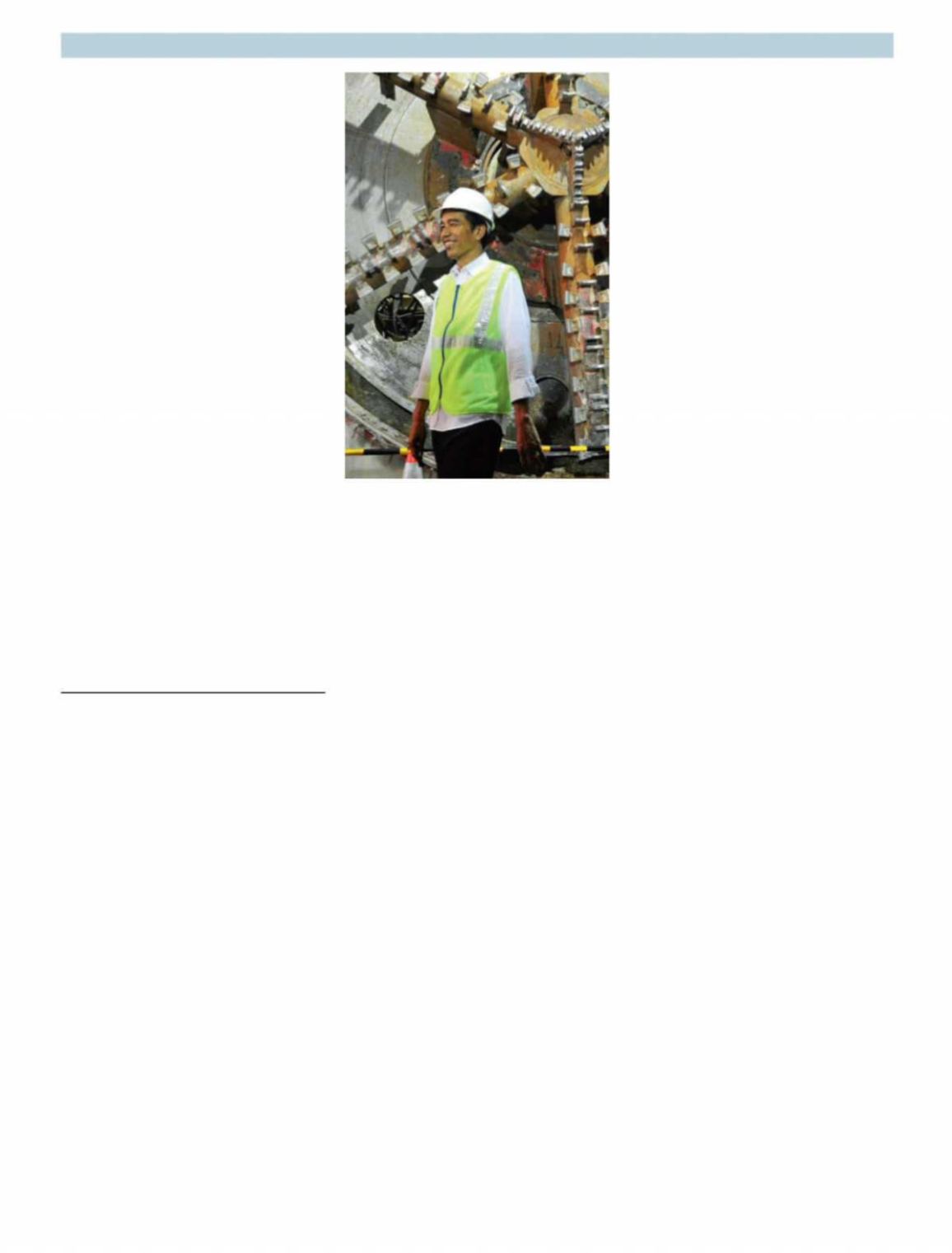

L

IKE many politicians, President Joko Wi-

dodo of Indonesia (known as Jokowi)

enjoys being seen in a hard hat. On April

23rdhe tweetedaphotoofhimselfresplen-

dent in a gleamingwhite one tohis10mfol-

lowerswhile visiting the site ofa future air-

port in Central Java. The previous week he

posted several photos ofhis trip to another

airport being built, this time in West Java,

complete with a hat and an orange con-

struction vest. (Pictured is Jokowi on yet

another such outing, to a mass-transit rail-

way project in Jakarta last year.) More sur-

prisingly for a head of state, many respons-

es to these tweets have been broadly

positive. The overwhelming impression

among Indonesians is that their president

gets shovels into the ground, as well as in-

specting their use before cameras.

After years of relative neglect, the

amount Indonesia spends on roads, rail-

ways, energy plants and the like has

surged. Jokowi’s predecessors promised

much but delivered little. But after he took

office in 2014, Jokowi took advantage of a

fall in the oil price to put a cap on an expen-

sive fuel subsidy provided by the govern-

ment. This gave him more fiscal leeway to

splurge on infrastructure projects. In that

year178trn Indonesian rupiah ($15bn) were

allocated to infrastructure in the state bud-

get. By 2017 the amount earmarked was

more than double that. Jokowi’s govern-

ment has plans for 222 “national strategic

projects” involving roads, railways,

bridges, power stations and much else. Of

these, 127 are under construction and over

20 have been completed. This year’s bud-

get calls for 856km of new roads to be built

across the archipelago.

The spending, sorely needed, has

boosted Jokowi’s popularity. According to

a survey in 2017 by the

ISEAS

Institute in

Singapore, nearly three-quarters of Indo-

nesians approved of his efforts, with rural

dwellers particularly keen on them. Some-

times he gets credit where it is not due. In

Medan, the capital of North Sumatra, a

new railway line between the city’s main

station and the airport has turned a jour-

ney that can take several hours by car to

one of only 55 minutes. The railway

opened in 2013 under the previous presi-

dent, but a banner in the station shows a

white-shirted Jokowi going through the

ticket gates. On the train, a video shows

him shaking commuters’ hands. People

waiting at the station express approval of

Jokowi and say the railway is an example

ofwhat he has done.

It is easy to see why Jokowi’s projects

are so popular. Many of the roads on and

between Indonesia’s 13,000 islands are

still terrible, havingbeenall but ignored for

decades under the highly centralised gov-

ernment of Suharto, Indonesia’s president

for three decades until 1998. In parts of ru-

ral South Sulawesi, for example, endless

potholes make for bone-rattling bus rides.

The capital desperately needs work on its

sewer system. In 2016 the city’s head of

planning estimated that only 4% of Jakar-

ta’s 10m residents had access to it. The rest

flush into drains through which the waste

flows untreated.

But even if Jokowi wins a second term

as president in 2019, which looks likely, it

may be hard for him to ensure that these

ambitious projects get finished. Complex

regulations do not help. Each sector—

roads, energy and so on—has its own laws

and regulatory bodies related to procure-

ment and drawing up contracts, says Jef-

freyDelmon, an infrastructure specialist at

the World Bank. So each has a different

way of doing things.

Indonesia also suffers from a shortage

of skilled labour and poor safety on con-

struction sites. On April 17th two people

were killed by the collapse of a bridge in

East Java and of an overpass being built in

North Sulawesi. Earlier this year an inter-

nal footbridge in the Jakarta Stock Ex-

change caved in, injuring over 70 people.

In Jakarta alone there were 10% more con-

struction accidents last year than in 2016.

Acquiring land is tricky, too. Plans for aChi-

na-backed high-speed railway between Ja-

karta and Bandung, a city in West Java,

have been held up for two years, partly be-

cause it is costly and complicated to move

so many people on one of the most dense-

ly populated islands in theworld.

The government’s big hand

Jokowi’s eagerness to get projects off the

ground has also introduced another pro-

blem: an over-reliance on state firms. Al-

though China and India in particular ap-

pear eager to invest in the archipelago,

many private investors only want to back

projects in Java, the most populous island,

rather than in rural parts. Despite Jokowi’s

pledge to ensure that only a third of infra-

structure is publicly funded, government

money is still being used extensively. By

one estimate, state enterprises are cur-

rently involved in 80% of the projects in

some shape or form. According to data

from the World Bank, private investment

only made up 9% of total investment in in-

frastructure in 2011-15, down from 19% in

2006-10.

At the mayor’s office in Medan, Ridho

Siregar, an employee there, praises Jo-

kowi’s infrastructure binge. In the past few

years new highways, bridges and dams

have helped to transform the city, the

fourth-biggest in the Indonesian archipela-

go. But the official admits there is an awful

lot to do. “Especially for the highways, it’s a

bit late,” he says.

7

Infrastructure in Indonesia

The hard-hat

president

MAKASSAR AND MEDAN

JokoWidodo’smost lasting legacymay

be in roads, railways and airports

Jokowi’s projects are no bore

РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News"

VK.COM/WSNWS