The Economist

May 5th 2018

7

FINANCIAL INCLUSION

2

1

SPECIAL REPORT

it work has not been straightforward. Agents delivering the cash

would take a cut. Almost all Pakistanis have a digital identity

stored in a national database that helps themopen a bank ormo-

bile-money account. But giving

BISP

recipients debit cards linked

to this so they could get themoney froman

ATM

also sometimes

meant that middlemen took the cards, withdrew themoney and

skimmed a commission. Mobile money works better, but it still

usually involves a visit to an agent. The number of mobile ac-

counts held by women in Pakistan rose by an impressive 4m in

the 12 months to September last year, to 7.3m, but those held by

men increased by an evenmore remarkable 12m, to 25.6m.

Similar obstacles slowdown the move from “cash-in-cash-

out” (

CICO

) systems to those inwhichmobilemoney is accepted

for day-to-day purchases. (Easypaisa is largely an “over-the-

counter” system in which both sender and recipient use cash

and the digital money moves from one agent to another.) The

aimis to increase the number ofindividualmobile accounts, and

then ofmobile payments. But so long as other shops accept cash,

an individual shopkeeper has little incentive to accept electronic

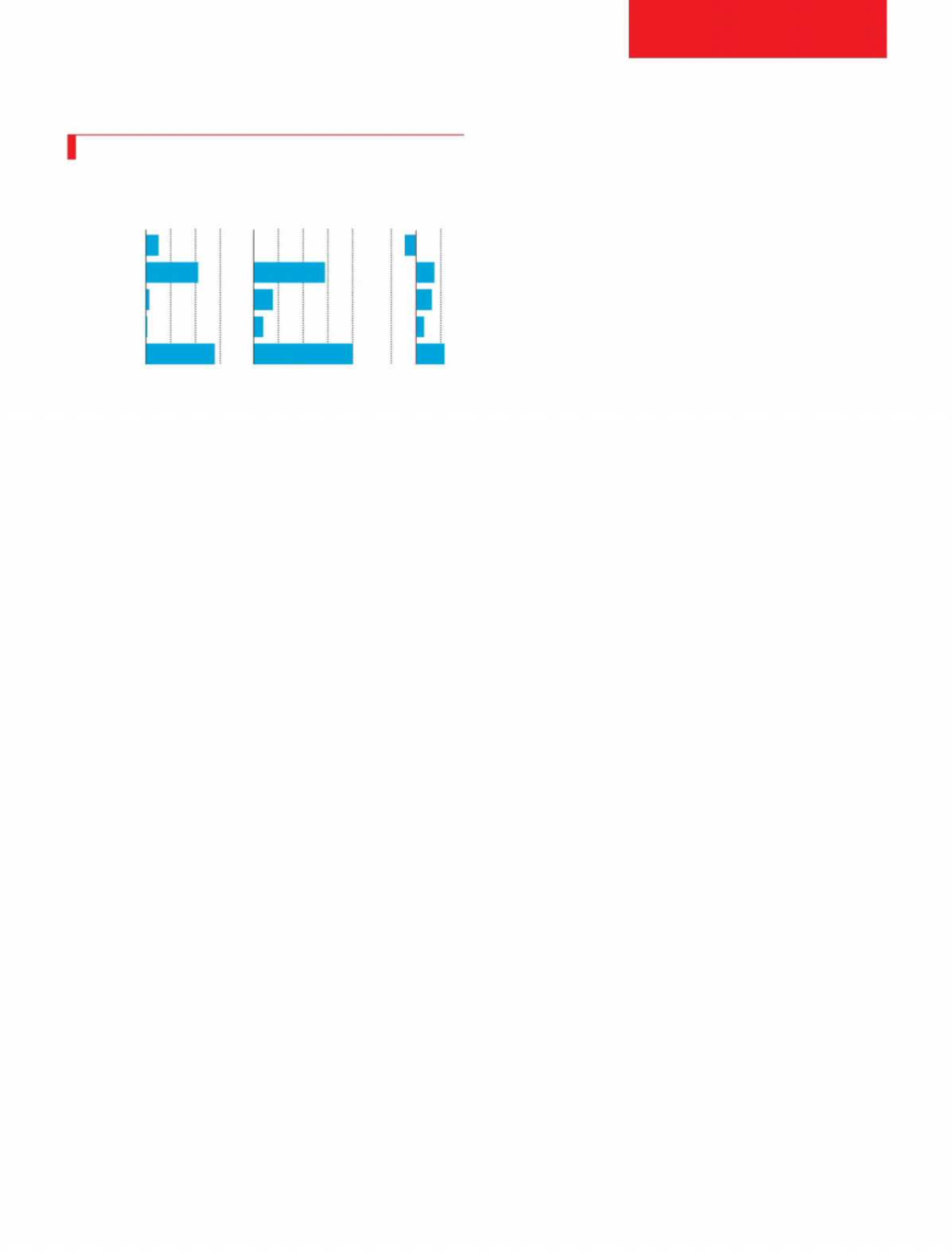

payments. And a new study byMcKinsey finds that

CICO

is still

crucial to current businessmodels formobilemoney, accounting

for about 60% of profits (see chart).

Cash is here to stay. “It works quite well,” notes McKinsey’s

Ms White drily. Even in Norway, where digital payments have a

bigger share than anywhere else, 17% of all payments are still in

cash. But digital payments will become easier and more com-

mon. “Tap-to-pay” methods using near-field communication

technology that have taken off in Europe, and the

EFTPOS

(elec-

tronic funds transfer at point ofsale) machines ubiquitous in rich

countries, may be supplanted in many developing ones by an

app on a small retailer’s smartphone. In Pakistan, as in much of

theworld, this is likely to be one that can read a

QR

code.

M-PESA

in Kenya, for example, is rolling out “scan-to-pay” aswell as “tap-

to-pay” services among itsmerchants.

Although cumbersome, electronic payments are possible

on a feature phone, and some such phones have cameras that

can read

QR

codes. But a smartphone makes them much easier,

raising another tension: between feature-phone-based services

and internet-enabled phones. In Pakistan the local subsidiary of

FINCA

, a global non-profit microfinance network, has a joint

venturewith

FINJA

, a local fintech, marketingamobilewallet for

smartphones called SimSim. That seems perverse in a country

where smartphones account for only about a quarter of mobile

connections. As elsewhere, however, that proportion is rising

rapidly thanks to cheapChinesehandsets. QasifShahidof

FINJA

argues that in the modern world those without a smartphone

lack a digital identity and are not really “included”. Designing

systems for them that rely on feature phones is “a ploy for people

to continue to belong to the have-nots”.

A final tension is between competition and the concentra-

tion implied by network effects. Rich countries have burgeoning

choices. Sit in a taxi in Singapore and thewindow is obscured by

stickers advertising different ways to pay for the ride—credit

cards, debit cards, stored-value cards and any number of smart-

phone apps. Shopcounters groanundertheweight ofall the

EFT-

POS

machines. But in frontier markets the brave pioneers ofmo-

bile money tend to become near-monopolies.

M-PESA

has 80%

of the market in Kenya. In Bangladesh the central bank has li-

censed 27 services, and Kamal Quadir claims a market share of

only 60% for bKash. But his network of 176,000 agents is hard to

match. As he says, “you need network effects and scale to be ef-

fective.” In Pakistan, Easypaisa and JazzCash, its biggest rival,

have amarket share of about 85% between them.

One way of both fostering greater take-up of digital finance

in the short term and mitigating the long-term risks of monopo-

lies is to embrace “interoperability”, allowing payments across

different systems. To this end the Gates Foundation has collabo-

rated with a number of fintechs, including Ripple, a highly val-

ued distributed-ledger developer, to create free open-source soft-

ware. The result, a systemcalledMojaloop (mojameans “one” in

Swahili), makes it easier to deploy interoperable payment plat-

forms. The idea is to ensure that the very poor will have access

whatever happens to the rest of themarket.

For now, intense competition inmost countries means that

disadvantaged consumers should indeed benefit from the rise in

mobilemoney. But competition is fierce in part because network

effects imply that the winner takes all. And as transferring mon-

ey gets ever closer to the goal of free, frictionless, real-time pay-

ments, what will matter is not so much the process itself as the

additional services the provider is offering.

7

CICOnomics

Mobile-money economics in emerging markets

2017, % of total baseline revenue

Source: McKinsey global banking

practice, March 2018

*Includes deposit insurance

†

Includes net interest margin

Accounts

nil

Cash-in-

cash-out

Transactions

Other

Total

Revenues

†

Profits

Costs*

0 25 50 75 100

0

– +

25

25

0 25 50 75

BLOCKCHAIN HOLDS GREAT potential for improving

payment systems, but for the moment that potential re-

mains largely unrealised. In March Swift, a Brussels-based ser-

vice owned by 11,000 banks that handles more than half of all

cross-border interbank payments, said further progress was

needed before distributed-ledger technology “will be ready to

support production-grade applications in large-scale, mission-

critical global infrastructures”. But it is coming, and cross-border

payments are in its sights. Also inMarch, at Money 20/20, a pay-

ment-industry gathering in Singapore, Ravi Menon, managing

director of Singapore’s central bank, argued that one of the stron-

gest possible uses for blockchain technology is to “facilitate

cross-border settlements”. Many think that Swift’s current pay-

ment systemwill move to the blockchain in the long run. In 2016

ICICI

, an Indian bank, and Emirates

NBD

of the United Arab

Emirates successfully tried out a networkbuilt by Infosys to han-

dle remittances from the Gulf to India. Ant Financial has pub-

lished49blockchainpatents,more thananyother companyany-

where. Stefan Thomas of Ripple says that 100 banks worldwide

are committed to deploying his firm’s “interledger protocol”

Blockchain and remittances

Not to the swift

Cheaper cross-border transfers are com

i

ng

РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News"

VK.COM/WSNWS