6

The Economist

May 5th 2018

SPECIAL REPORT

FINANCIAL INCLUSION

2

1

where it plans to launchWeChat Pay—its first forayoutsideChina

and Hong Kong. Alipay has taken a higher-profile approach, en-

listing merchants in Europe and America to accept it as a means

ofpayment for the benefit ofChinese residents and tourists. And

in Asia itself, Ant Financial has been investing in local mobile-

payment services in India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines,

Singapore, South Korea and, most recently, Pakistan.

The Chinese are coming

This last investment, of$184.5m, is to buy 45%ofTelenorMi-

crofinance Bank (

TMB

), which manages Pakistan’s biggest mo-

bile-money service, Easypaisa. Owned by Telenor, a Norwegian

multinational mobile-network operator,

TMB

launched Easy-

paisa in 2009. Competitors in Pakistan view Ant’s arrival with

some foreboding. “They are here not to save the poor Pakistani

but topromote e-commerce,” says one localmicrofinance lender.

It is hardly surprising that many in this industry, rooted in

charitable development work, feel ambivalent about vast com-

mercial enterprises entering the payment business. The suspi-

cions are not confined to Pakistan, and are likely to becomemore

acute as American and Chinese tech giants slug it out for market

share in poor countries (see box). As a still largelynascent market

of enormous potential, Pakistan also illustrates many of the oth-

er tensions affecting the payment business.

One is between the desire of both governments and busi-

nesses to digitise payments swiftly and the capacity of the pop-

ulation to go alongwith that. Moving away from cash payments

reduces costs, cuts leakages through corruption, discourages the

informal economy and increases the tax base. The poor may be

equally quick to realise that mobile money is more secure from

robbers, can save themhours of travelling and queuing andmay

open up a range offinancial services. But theymay struggle to af-

ford even a simple feature phone, and the illiterate and innumer-

ate especiallymay find using it daunting at first.

In Pakistan that covers a big chunk of the population. The

overall adult-literacy rate of 58% hides lower shares in the coun-

tryside (49%) andamongwomen (45%). The drive forfinancial in-

clusion may not narrow the gender gap. Pakistan’s Benazir In-

come Support Programme (

BISP

), which offers cash transfers to

the neediest women, seemed a good way to do that, but making

DRUMBEATERS FOR FINANCIAL inclusion are

excited about India. With190m adults with-

out bank or mobile-money accounts, of

whom an estimated100mhave mobile

phones, it is second only to China in its

potential. It has also become, in the words of

Greta Bull, the chief executive of the Consul-

tative Group to Assist the Poor, where “Sil-

icon Valley battles China”.

Successive Indian governments have

actively promoted both the opening of bank

accounts and the expansion of digital money.

To nurture Aadhaar, the national-identity

digital database, the previous Indian govern-

ment in 2009 recruited Nandan Nilekani, a

former boss of Infosys, a big Indian software

and outsourcing firm. Now back at Infosys, he

says that the current Indian government is

evenmore enthusiastic about the project.

Both administrations recognised, he says,

that it is “the only way to achieve financial

inclusion at scale”. In some ways, he adds,

“we have leapfrogged the rich world.”

Indians now have about 800mbank

accounts linked to Aadhaar. Account-holders

do not even need a phone to get at their

money. Some merchants have thumbprint

readers. Aadhaar forms part of what is called,

in techie jargon, the “India Stack”, a set of

interlinked digital platforms that allow

smooth transfers to and frombank accounts

via a “Universal Payments Interface” (

UPI

).

Bank accounts can be linked to a

UPI

address,

allowing immediate payment to be made

fromone account to another.

Launched in 2016, it has had a decent

start. By this March it was handling around

178m transactions, worth about $3.6bn,

reaching a larger number in18months than

credit cards have managed in India in18

years. Dilip Asbe, chief executive of the

National Payments Corporation of India, the

bank-owned non-profit organisation respon-

sible for the

UPI

, says that it will be small

merchants who ultimately determine suc-

cess. As the systembeds in, he believes that

more andmore of themwill start accepting

QR

-code-based payments.

Global giants are now competing to

develop applications for this interface.

Google launched an app called Tez (Hindi for

“fast”) last September. By this March it

already had14m active users a month and

was accepted as a formof payment by over

500,000merchants. Designed to resemble a

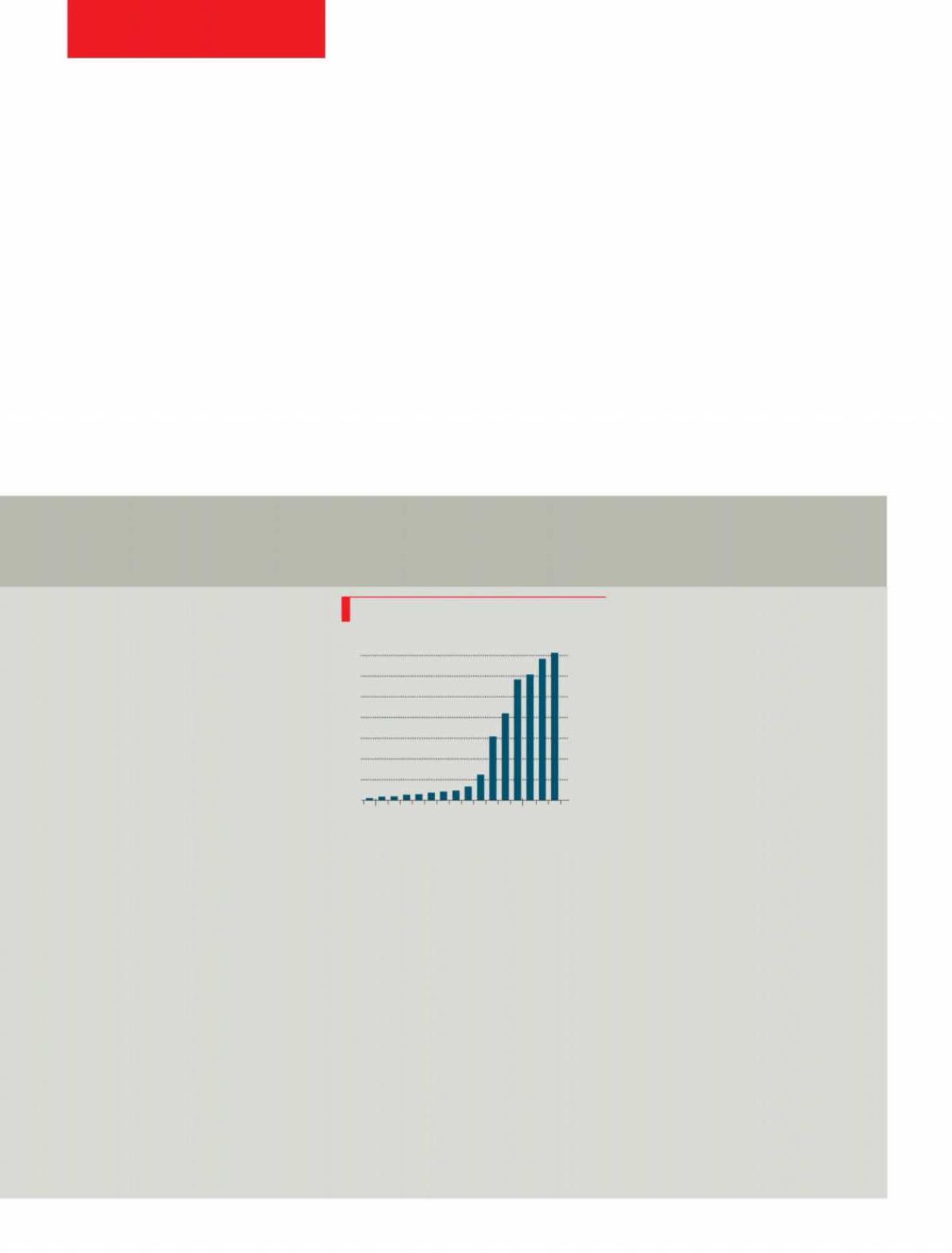

Stack’em high

India is becoming an important battlefield for financial inclusion

messaging system, it also offers “proximity

payments”—two nearby phones can be

paired through an ultrasound signal (“au-

dio

QR

”) andmoney sent between them

without the phone number or any other

personal details being shared (a relief, in

particular, tomany women). WhatsApp, a

messaging service owned by Facebook, has

also been experimenting with a

UPI

-based

payments system.

But the biggest rival is a domestic

online retailer andmobile-payment firm,

Paytm (for “pay throughmobile”), which in

February handled 40%of India’s

UPI

pay-

ments. Claiming over 300m accounts, it

provides the country’s most popular mobile

wallet. Alibaba and Ant Financial are minor-

ity shareholders. Around150 Ant engineers

have worked in India on Paytm’s systems at

one time or another. Tencent, meanwhile,

has invested in PhonePe, a mobile-payments

competitor offered by Flipkart, another

Indian online retailer.

Mobile payments got a big boost in

November 2016 when India’s prime minister,

Narendra Modi, abruptly announced the

withdrawal of high-value banknotes, which

made up 86%of the rupees in circulation. The

number of Paytm accounts increased from

115m at the time of the announcement to

160m in just 60 days. In retrospect, this can

be seen as one of the stages in a payment

revolution in India. The final destination

seems an unlikely one for such a poor coun-

try, but according to Mr Asbe, “the ultimate

aim is to replace cash.”

The Ind

i

a Stack

Sources: Reserve Bank of India; NPCI

U

nifi

e

d P

ay

m

e

n

ts I

n

te

rf

ace, t

r

a

n

sact

i

o

n

s,

m

D

2016

J F M

J F M

A M J J A S O N D

17

18

0

25

50

75

100

125

150

175

РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News"

VK.COM/WSNWS