The Economist

September 22nd 2018

United States 25

1

T

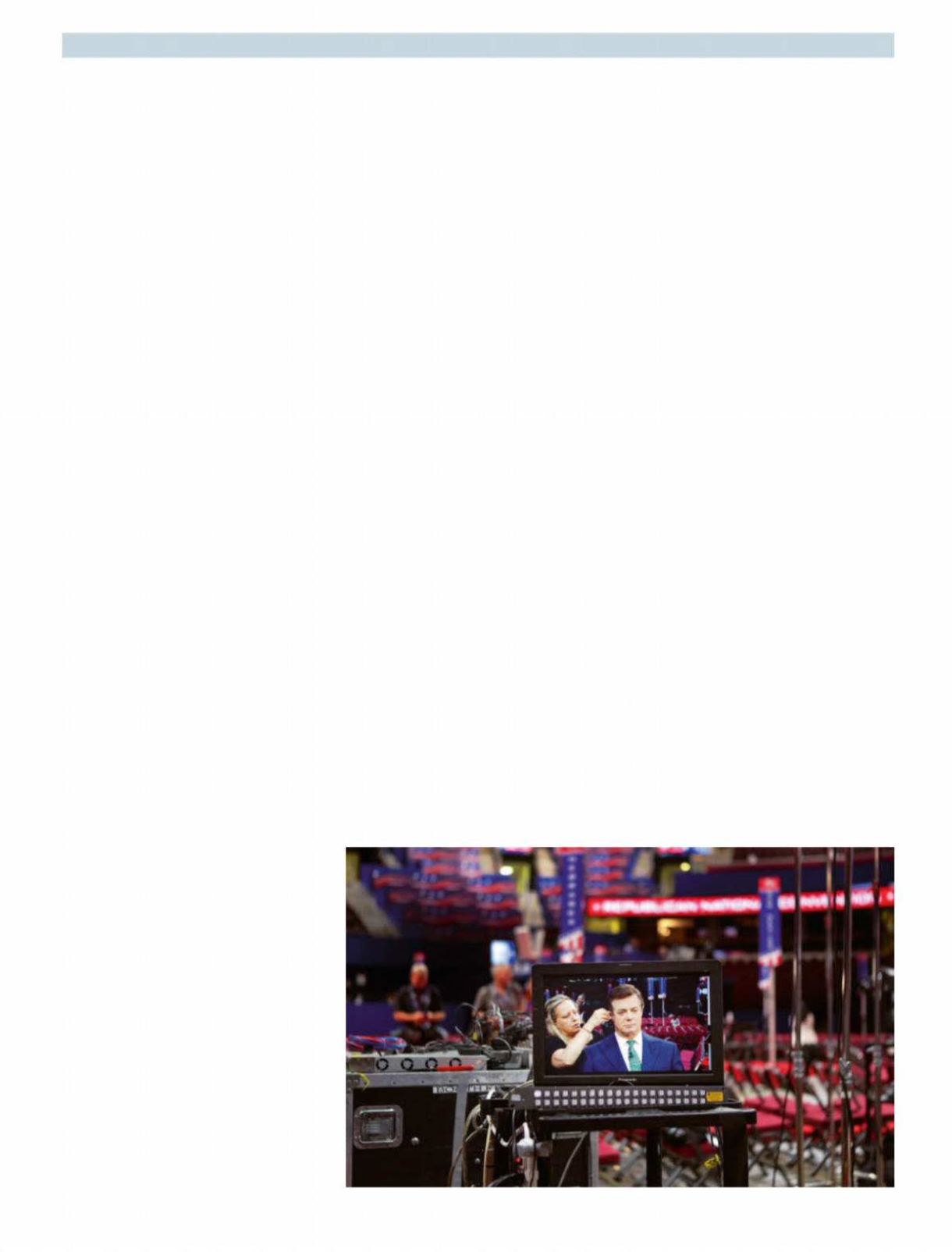

HE legal woes of Nisar Chaudhry, a 71-

year-old Pakistani national living in

Maryland, would be otherwise forgetta-

ble. But Mr Chaudry, who as self-appoint-

ed president of the Pakistan American

League had tried to parlay his title into po-

litical influence on behalf of the Pakistani

government, pleaded guilty to a rare sort

of crime: failing to register as a foreign

agent. That was precisely the crime that

Paul Manafort, President Donald Trump’s

disgraced former campaign-manager,

pleaded guilty to on September14th. Many

have focused on what Mr Manafort, who

was convicted on eight counts of financial

crimes in a separate trial in August, might

tell Robert Mueller, the special counsel in-

vestigating the Trump campaign’s possible

collusion with Russia. Of that, much is

speculated, but little is known.

Yet the nature of Mr Manafort’s crimes

has also shed light on unregistered foreign

lobbying, the murkiest part of a swampy

industry. The scheme, detailed in Mr Ma-

nafort’s guilty plea, was to funnel $11m

over a decade into America to fund lobby-

ing efforts for Viktor Yanukovych, the pro-

Russian former prime minister of Ukraine.

Heworked to plant stories unfavourable to

Yulia Tymoshenko, a political rival of Mr

Yanukovych, and arranged for a “Haps-

burg Group”, made up of four former

heads of European states, to lobby on be-

half of the Ukrainian government. One of

them managed to lobby Barack Obama

and Joe Biden directly in the Oval Office.

The number of unregistered foreign

lobbying schemes currently in effect is un-

known. By the official numbers, foreign

governments have officially spent $532m

on lobbyists and communications experts

to influence American policy since 2017.

Experts reckon that the undeclared

amount is at least twice as large. “My joke is

that it’s like seeing a mouse. For every one,

there are five others in the house,” says Ben

Freeman, director of the Foreign Influence

Transparency Initiative at the Centre for In-

ternational Policy, a think-tank.

The principal defence against secret for-

eign influence over American politics is

the ForeignAgents RegistrationAct (

FARA

).

It is a rickety piece of legislation, construct-

ed in1938 to combatNazi propaganda. It ex-

plicitly mentions typewriters, parchment

paper and the copying press—the technol-

ogy used to duplicate papers that George

Washington used. Worse, it is extremely

vague, and could potentially sweep all

sorts of harmless behaviour into illegality.

Formuch of its existence

FARA

has been ig-

nored, because it requires lots of pesky pa-

perwork and the Department of Justice

(

DoJ

) didnot caremuch. Between1966 and

2015 the agency brought only seven crimi-

nal cases for violations. Then Mr Mueller

made it great again, charging senior Trump

associates like Mr Manafort, Rick Gates,

the campaign’s deputy chairman, and Mi-

chael Flynn, the president’s short-lived na-

tional security adviser. New registrations

have nearlydoubled, from550 in 2016 to an

estimated 920 this year.

Ukraine-drain

Fewattempts at disclosed foreign lobbying

are as brazenasMrManafort’s undisclosed

venture was. More often they reside in the

murky exemptions provided in

FARA

. One

is for people solely engaged in “bona-fide

religious, scholastic, academic or scientific

pursuits”. How bona-fide scholarship dif-

fers from political activity is unclear in the

statute and barely considered in the case

law. Many institutions tread this blurry

line. Confucius Institutes, centres for Chi-

nese language instruction overseen by the

Chinese Ministry of Education, estab-

lished at many universities worldwide,

have been criticised as propaganda outlets.

A Korean-funded think-tank at Johns Hop-

kins University closed in May; the South

Korean government withdrew funds after

officials reportedly tried to fire the director

over a difference of opinion.

Think-tanks can also serve as vehicles

for influence-peddling. Prominent think-

tanks, like Brookings and the Centre for

Strategic and International Studies, have

been embarrassed after revelations that

they accepted millions of dollars from for-

eign governments while also producing

seemingly objective research on subjects

dear to them. Lesser-known outfits can

project more seriousness than an out-and-

out lobbyist. The Arabia Foundation, a re-

cently founded think-tank often quoted in

American media, is thought to be close to

the Saudi government. Ali Shihabi, the

founder, says the think-tank is funded by

private Saudi citizens and that “we are not

involved in anymanner of lobbying”.

Another think-tank, theNational Coun-

cil on

US

-Arab Relations, retains an inter-

national fellow named Fahad Nazer who

has written for prominent think-tanks and

newspapers. A filing to the

DoJ

made by

Mr Nazeer shows that he became a paid

consultant to the Saudi Arabian embassy

in November 2016, receiving a salary of

$7,000 a month. The think-tank at which

Mr Nazer is a fellow declined to comment

on the arrangement; Mr Nazer says he

complieswith all the laws and regulations,

and is careful to mention his deal with the

Saudi embassy inmedia appearances.

Rather than pursuing think-tanks, the

DoJ

has focused its attention on govern-

ment-funded news agencies. After a pro-

tracted battle,

RT

, a television network

funded by the Russian government, was

made to register as a foreign agent in No-

vember 2017. On September 18th the

Wall

Street Journal

reported that the

DoJ

had or-

deredXinhua and

CGTN

, twoChinese-run

media outlets, to register as foreign agents.

But the legal argument that compels

RT

to

register as a foreign agent but not the

BBC

,

which is fundedbya tax, ismysterious. De-

cisions over who or what is subject to

FARA

seems largely at the discretion of the

Foreign lobbying

Crimea river

WASHINGTON, DC

PaulManafort’s dodgyworkwithUkraine shines light on a swampybusiness

The full-fee service