20 Briefing

Latin America

The Economist

September 22nd 2018

2

people in the country. Politicians and the

courts have made modest changes to the

electoral system. The supreme court has

banned corporate donations to parties,

which has cut the cost of this year’s elec-

tion by 70-80%, estimates ChrisGarman of

Eurasia Group, a consultancy. Congress

has enacted a “performance clause”,

which eliminates public funding and me-

dia time for parties that get less than1.5% of

the national vote distributed across at least

nine states (the threshold will eventually

rise to 3%). This may reduce the number of

parties in congress.

But the changes these reforms will

bring about will be gradual, if they happen

at all. One reason is that Lava Jato has

sharpened the incentive for politicians to

cling to office. That is because sitting politi-

cians can be tried only by the supreme

court. At least 30 people suspected of

wrongdoing are running for re-election, ac-

cording to

Folha de S.Paulo

, a newspaper.

Mr Garman estimates that 70% of the new

lower housewill consist ofholdovers from

the current one, up from a re-election rate

in the current congress of 55%. The ban on

corporate donations hasmade it harder for

newcomers to challenge incumbents.

The next congress and president will be

caught between the pressure for further re-

formand a desire for self-preservation. The

bolder ideas range from carving up states

into electoral districts to scrapping Brazil’s

presidential system in favour of a parlia-

mentaryone, but it is hard to see legislators

changing so drastically the system that

elected them. More feasible are proposals

to improve regulation of lobbying and pro-

curement by government agencies and

state firms. Voters will demand that Lava

Jato continue unimpeded; politicians may

try to put grit in the judicial machinery.

“The political system will try to limit the

power of legal institutionswhatever the re-

sults of the election,” predicts Oscar Vil-

hena, dean of the law school at Fundação

GetulioVargas, a university. If the next gov-

ernment continues to buy support with

pork and patronage, but limits outright

bribery, that would be a big improvement.

Bringing economic relief may be easier

than attempting political renewal. That is

what Mr Temer tried to do after he took

over from Ms Rousseff in 2016, with some

success. Congress enacted a constitutional

amendment that freezes federal spending

in real terms at least until 2026. Another re-

form made the labour market more flexi-

ble. Mr Temer came close to a reformof the

pension system in May last year, when a

newspaper made public an audio tape on

which he appeared to endorse the pay-

ment of hush money to a politician con-

victed of taking bribes. Mr Temer spent his

political capital to avoid prosecution.

The aborted reform leaves Brazil’s econ-

omy in a parlous state. The budget deficit is

equivalent to 7% of

GDP

. Spending on pen-

sions for retired public employees and for-

mal-sector workers accounts for 56% of

federal spending and is growing at a rate

four percentage points above inflation. Tax

giveaways, expanded by Ms Rousseff’s

government, are more than 4% of

GDP

.

This, plus the slowgrowthof the economy,

is raising debt to unsustainable levels.

Gross public-sector debt rose from 78% of

GDP

in 2016 to 84% last year.

The danger is not that Brazil will go the

way of next-door Argentina, which has

had to seek help from the

IMF

(see Ameri-

cas section). Unlike Argentina, Brazil owes

money mainly in its own currency and to

its own citizens, so declines in the value of

the real do not greatly increase its net in-

debtedness. The country has $380bn of re-

serves, equivalent to a fifth of

GDP

.

The cupboard is bare

But that does not mean that Brazil is in the

clear. Doubts about its financial stability

will weigh on the real, which in turn will

raise inflation. Real incomes, investment

and growth will suffer. With non-discre-

tionary spending such as pension benefits

consuming more than 90% of the federal

budget, little is left over for such services as

health. Many state governments, which

are responsible for policing and education

among other things, are in even worse fis-

cal shape. Economists reckon that Brazil

needs spending cuts or revenue rises of

300bn reais a year, equivalent to 4% of

GDP

, to stabilise federal debt.

Most presidential candidates now ac-

cept that pensions need to change. That is

partly because voters have come to resent

a system that lets bureaucrats retire in their

50s, often with full salary. Opposition to

the sort of reform that Mr Temer proposed

dropped from 68% to 44%, according to

polls commissioned by the government.

There is also agreement on the need to

raise tax revenue, although the details vary

among candidates.

Despite this glimmer of consensus,

markets are pessimistic. The real has fallen

to a record low against the dollar. In part

that is because the candidates likeliest to

win the presidency are least equipped to

govern. Both the front-runners represent

polarising forces. They will have a hard

time getting support for reforms. Candi-

dates with the best economic ideas are un-

likely tomake it into the second round.

Mr Bolsonaro’s main talent is for whip-

ping up public anger. He trumpets a new-

found interest in liberal economics. His

chief economic adviser is Paulo Guedes,

who was educated at the University of

Chicago, a nursery of market-minded

economists. Mr Bolsonaro belongs to the

tiny Social Liberal Party and has few allies.

“Our party is the people,” he declares. Un-

less he makes peace with the political

class, he is unlikely to get his reforms

through congress.

Mr Haddad, his likeliest opponent in

the second round, has a bigger party be-

hind him and was a successful mayor. He

promises to put debt “on a downward

path”. But his party is less reform-minded

thanhe is. Hewill struggle to shake the per-

ception that he is Lula’s puppet.

The other main candidates are less po-

larising, and less likely to push voters into

the arms ofMr Bolsonaro in the run-off. All

have drawbacks. Ciro Gomes, a left-wing

former governor of the north-eastern state

of Ceará, favours interventionist policies

of the sort that aggravated Brazil’s eco-

nomic crisis, such as subsidised lending.

Two centrists are mirror images of each

other. GeraldoAlckmin, a former governor

of the state of São Paulo, is competent and

backed by an enormous coalition, which

bodes well for his ability to enact eco-

nomic reforms. But he is colourless and be-

longs to the Party of Brazilian Social De-

mocracy (

PSDB

), which is among the most

tarnished by Lava Jato. More inspiring is

Marina Silva, a former environmentminis-

ter who was born into an illiterate rubber-

tapping family in the Amazon and learned

to read when she was 16. Ms Silva shares

Mr Bolsonaro’s unwillingness to engage in

pork-barrel politics, which will make go-

verning hard. She is more likely than the

populist to stick to her resolve.

The voters of Alagoas seem torn be-

tween the handouts and compromises

that come with old-style politics and the

hope of something better. Rodrigo Cunha,

a candidate for senator from the

PSDB

, is

promising reform. Running on an anti-cor-

ruption platform, he is putting up a strong

challenge for one of the two senate seats

up for grabs. But Alagoans alsohave a prag-

matic streak. Jurandi Pimentel, an unem-

ployed taxi driver, says he will vote for Mr

Cunha, but his other senatorial vote will

go to Mr Calheiros. “Alagoas would die

without someone who knows how to do

politics like the rest of them,” he says.

7

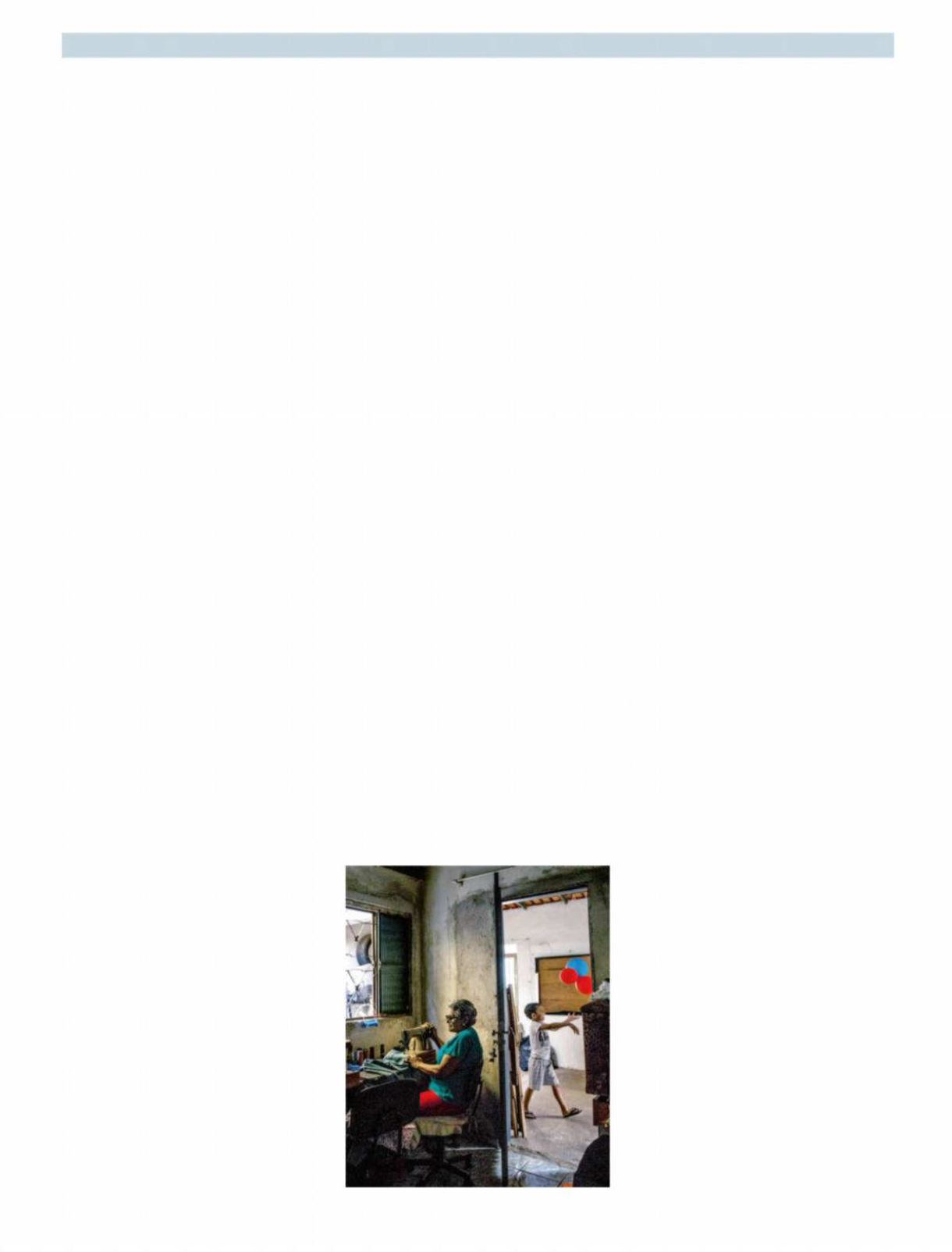

Her pension, or his education?