The Economist

September 22nd 2018

Briefing

Latin America

19

1

2

lar politician, and its most despised. His re-

placement as the nominee of the Workers’

Party (

PT

) is Fernando Haddad, a former

mayor of the city of São Paulo. Polls sug-

gest he has the best chance of meeting Mr

Bolsonaro in the run-off.

If that happens, the presidential elec-

tionwill be a contest between Lula’s party,

which is more responsible than any other

for the deepest traumas Brazil has suffered

since the end of the dictatorship in 1985,

and a candidate who represents an ex-

treme response to them. The first of those

traumas is the corruptionunearthedby the

Lava Jato (“CarWash”) investigations. It in-

volved politicians and parties taking kick-

backs from private-sector companies that

won contracts from state-owned firms or

extracted other benefits from the state.

More than a hundred politicians have

been investigated; 12 have been convicted,

including Lula. His successor, Dilma Rous-

seff, was impeached in 2016 on unrelated

charges. The current president, Michel

Temer, a member of the

MDB

, has avoided

trial in the supreme court only because

congress voted to protect him from it. The

suspects in Alagoas include Mr Calheiros,

who faces several inquiries, and Benedito

de Lira, a

PP

senator backed by Mr Gaia

who is running for re-election.

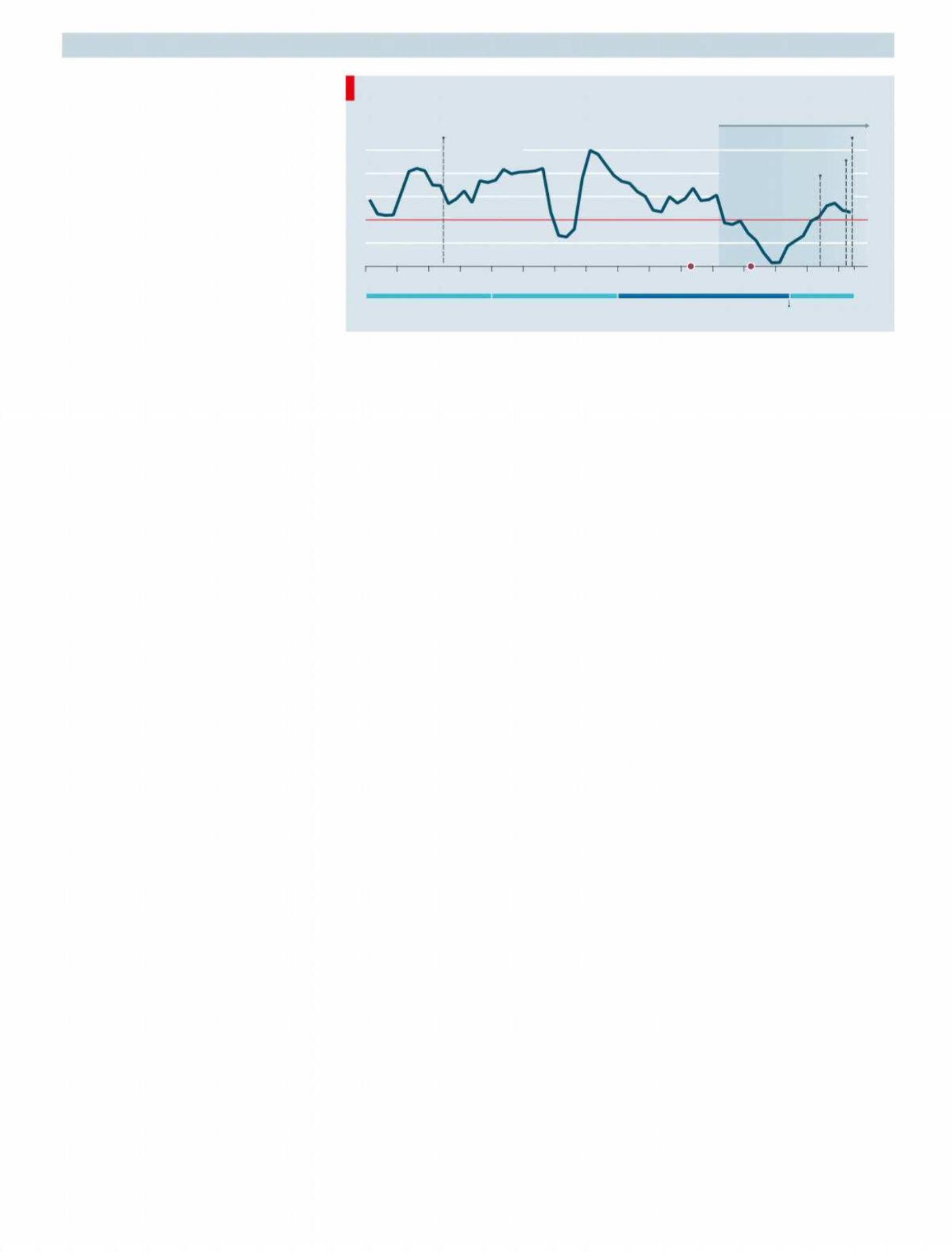

The second trauma is Brazil’s worst-

ever recession, which started as Lava Jato

was gettingunderway in 2014 (see chart). It

slashed

GDP

per person by 10% and

dragged back into poverty millions of Bra-

zilians who had entered the middle class.

Although growthhas resumed, it is a feeble

1.4% a year. A further cause of dismay is

crime. The number ofmurders rose 3% last

year, to a record of nearly 64,000.

These crises have shaken Brazilians’

faith in democracy. Just 13% were satisfied

with their democracy last year, the lowest

share in Latin America, according to Lat-

inobarómetro, a pollster. Rebelliousness

has been evident since 2013, when demon-

strations in São Paulo over a rise in bus

fares spread to other cities and over other

issues, including the poor quality of public

services. A ten-day strike by lorry drivers

in May this year over a rise in fuel prices

paralysed the economyand forced the gov-

ernment to restore subsidies temporarily.

At stake in the elections is whether Bra-

zil’s next cohort of leaders can provide

good enough governance to contain such

conflicts and restore trust in the country’s

institutions. That depends in turn on mak-

ingprogress on three big tasks. The first is to

rid politics as much as possible of the graft

that has brought democracy intodisrepute.

The second is to avert a slow-moving eco-

nomic crisis that threatens to condemn

Brazil to slow growth, high inflation and

impotent government. The third is to re-

duce violence.

Any government that tries to stabilise

Brazil will provoke conflict with groups

that lose from reforms. Expect another

round with lorry drivers over fuel subsi-

dies, which are scheduled to expire in De-

cember. A president serious about clean-

ing up politics will clash with

congressmenwhose support he or shewill

need to pass economic reform. Fighting

crime will require better co-ordination be-

tween the federal government and the

states, and between separate police forces

within states. If Mr Bolsonaro becomes

president, the next government might ac-

complish none of the above.Worse, his au-

thoritarian instincts might weaken Brazil-

ian democracy still further.

In theory, the elections offer the pos-

sibility of renewal. Brazilians will choose

the president, all 513 members of the lower

house of congress, two-thirds of the 81-

member senate and governors and legisla-

tures in all 27 states. But thewaypoliticking

is done in Alagoas shows why renewal

will be hard. Voters face a bewildering ar-

ray of parties, most of which stand for

nothing, and candidates, most of whom

are non-entities. Nationwide, the number

of parties has expanded fromseven in1988

when the constitution was adopted to 35

now; 28 are represented in congress. Most

exist only because they are entitled to pub-

licmoney and time on 25-minute-long pro-

grammes of advertising, which are broad-

cast twice a day during campaigns.

Aggregator parties like the

MDB

assemble

smaller ones into pre-election coalitions,

acquiring their broadcast time in exchange

for future government jobs.

Tears of a clown

The plethora of candidates comes from

Brazil’s unusual system of “open-list pro-

portional representation” for electing dep-

uties to the lower house of congress and

state legislatures. If a candidate amasses

more votes than he needs to get elected,

the excess is distributed to others in his co-

alition. Brazilians call this the “Tiririca ef-

fect”, after a clown whose spare votes in

2010 brought in three other deputies. Low-

er-house deputies represent their entire

states. This means they have to spend lots

ofmoney to get elected and have little con-

nection to their constituents.

In Alagoas, 441 candidates are running

for 40 legislative and executive jobs. To

anyone concerned about political consis-

tency, their alliances make no sense. On

September 6th a drum-banging, flag-wav-

ing throng held a march on the outskirts of

Maceió, Alagoas’s capital, for Mr Calheiros

and his son, Renan Calheiros Filho, the go-

vernor. Among the marchers were politi-

cians from the Communist Party as well as

the conservative Party of the Republic. A

week earlier, the Calheiroses held a rally

with Mr Haddad, even though the

MDB

has its own presidential candidate, Hen-

rique Meirelles, a former finance minister.

That is because Lula, Mr Haddad’s mentor,

is remembered as a president who brought

prosperity to many poor Brazilians, espe-

cially in the north-east. “It’s a calculus for

political survival,” says an adviser to the

Calheiros campaign.

Rather than a mandate for governing,

elections held under these conditions pro-

duce the opening positions of a game

played between the president and a frag-

mented congress, which Brazilians call

pre-

sidencialismo de coalição

(“coalition presi-

dentialism”). This entails the president

assembling a coalition of parties, which

has little to do with ideology and may not

be the same as the pre-election coalitions,

to enact his or her governing programme.

The glue is government jobs for suppor-

ters, money for crowd-pleasing projects

and, especially in recent years, graft on an

epic scale.

Brazilians have reached the end of their

patience with this system. In a poll con-

ducted late last year, 62% of respondents

identified corruption as Brazil’s biggest

problem. It is the biggest reason for the rise

ofMrBolsonaro,whoportrayshimself as a

scourge of the establishment, even though

he has been a congressman for 28 years

and belonged to nine different parties.

Despite the despair, the system has

shown that it has some capacity to reform

itself. Lava Jato shows that prosecutors and

judges are eager to exercise the indepen-

dence guaranteed to them under the con-

stitution by going after the most powerful

Fluctuating fortunes

Sources: Haver Analytics;

The Economist

Brazil, GDP, % change on a year earlier

2003 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

6

3

0

3

9

6

+

–

Presidents

Michel Temer

impeached

Dilma Rousseff

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva

Trucker strike

Leaked recordings

suggest Michel Temer

endorsed hush-money

payment

corruption and

recession

Protests against rise in transport fees

Mensalão

scandal

breaks, exposing

vote-buying in congress

Lula arrested

Operation

Lava Jato