The Economist

May 5th 2018

Finance and economics 71

2

I

NTEREST rates are heading higher and

that is likely to put financial markets un-

der strain. Investors and regulatorswould

both dearly love to knowwhere the next

crisis will come from. What is the most

likely culprit?

Financial crises tend to involve one or

more of these three ingredients: excessive

borrowing, concentrated bets and a mis-

match between assets and liabilities. The

crisis of 2008was so serious because it in-

volved all three—big bets on structured

products linked to the housing market,

and bank-balance sheets that were both

overstretched and dependent on short-

term funding. The Asian crisis of the late

1990s was the result of companies bor-

rowing too much in dollars when their

revenues were in local currency. The dot-

com bubble had less serious conse-

quences than either of these because the

concentrated bets were in equities; debt

did not play a significant part.

It may seem surprising to assert that

the genesis of the next crisis is probably

lurking in corporate debt. Profits have

been growing strongly. Companies in the

S

&

P

500 index are on target for a 25% an-

nual gain once all the results for the first

quarter are published. Some companies,

like Apple, are rolling in cash.

But plenty are not. In recent decades

companies have sought tomake their bal-

ance-sheets more “efficient” by raising

debt and taking advantage of the tax-

deductibility of interest payments. Busi-

nesseswith spare cashhave tended to use

it to buy back shares, either under pres-

sure fromactivist investors or because do-

ing so will boost the share price (and thus

the value of executives’ options).

At the same time, a prolonged period

of low rates has made it very tempting to

take on more debt.

S

&

P

Global, a credit-

rating agency, says that as of 2017, 37% of

global companies were highly indebted.

That is five percentage points higher than

the share in 2007, just before the financial

crisis hit. By the same token, more private-

equity deals are loading up on lots of debt

than at any time since the crisis.

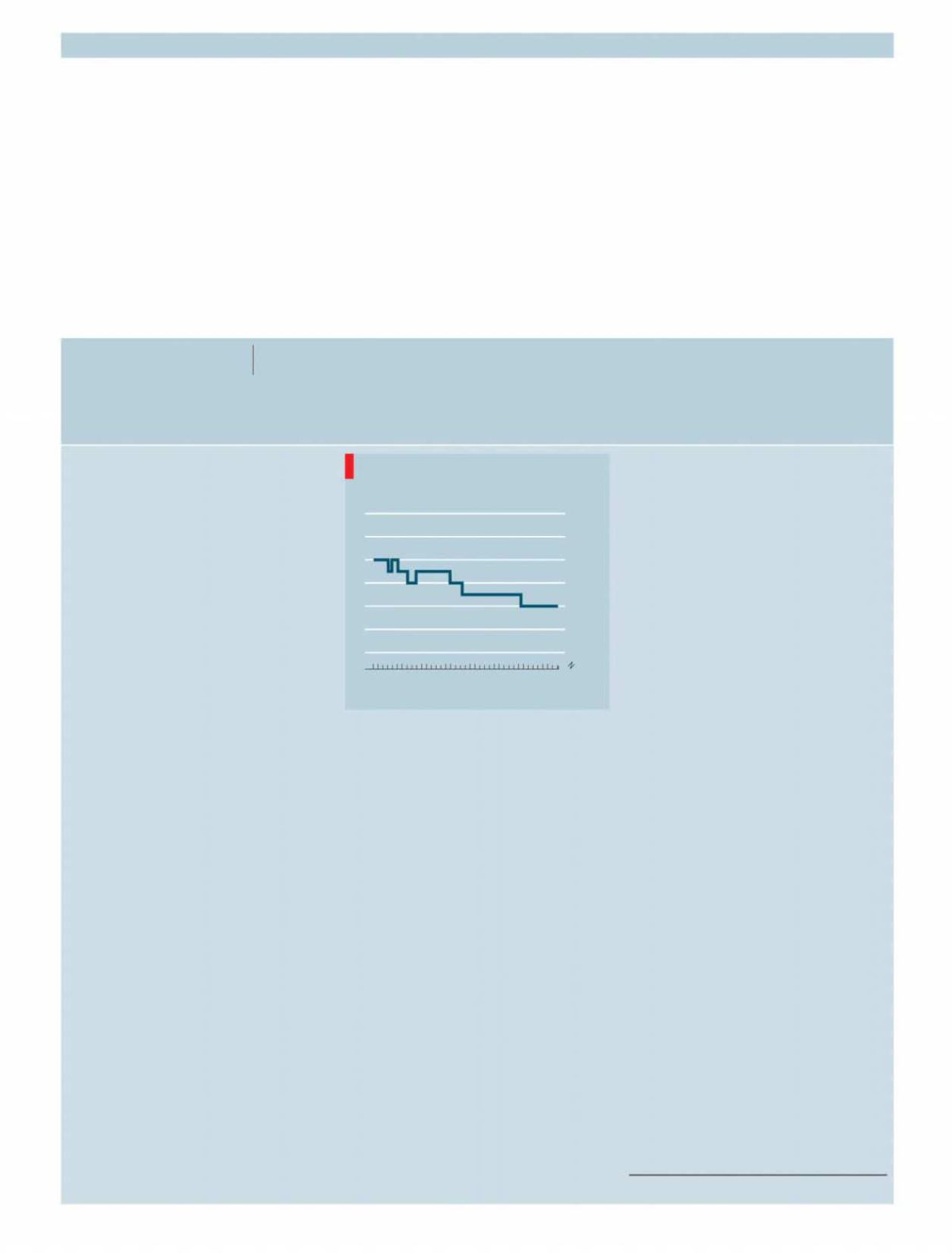

One sign that the credit quality of the

market has been deteriorating is that, glob-

ally, themedian bond’s rating has dropped

steadily since 1980, from

A

to

BBB

- (see

chart). The market is divided into invest-

ment grade (debt with a high credit rating)

and speculative, or “junk”, bonds below

that level. The dividing line is at the border

between

BBB

- and

BB

+. So the median

bond is nowone notch above junk.

Even within investment-grade debt,

quality has gone down. According to

PIMCO

, a fund-management group, in

America 48% of such bonds are now rated

BBB

, up from 25% in the 1990s. Issuers are

alsomore heavily indebted than before. In

2000 the net leverage ratio for

BBB

issuers

was1.7. It is now2.9.

Investors are not demanding higher

yields to compensate for the deteriorating

qualityofcorporate debt; quite the reverse.

In a recent speech during a conference at

the London Business School, Alex Brazier,

the director for financial stability at the

Bank of England, compared the yield on

corporate bonds with the risk-free rate

(the market’s forecast for the path of offi-

cial short-term rates). In Britain investors

are demanding virtually no excess return

on corporate bonds to reflect the issuer’s

credit risk. In America the spread is at its

lowest in 20 years. Just as low rates have

encouraged companies to issue more

debt, investors have been tempted to buy

the bonds because of the poor returns

available on cash.

Mr Brazier also found that the cost of

insuringagainst a bond issuer failing to re-

pay, as measured by the credit-default-

swap market, fell by 40% over the past

two years. That makes it seem as if inves-

tors are less worried about corporate de-

fault. But a model looking at the way that

banks assess the probability of default,

compiled by Credit Benchmark, a data-

analytics company, suggests that the risks

have barely changed over that period.

So investors are getting less reward for

the same amount of risk. Combine this

with the declining liquidity of the bond

market (because banks have withdrawn

from the market-making business) and

you have the recipe for the next crisis. It

may not happen this year, or even next.

But there are already ominous signs.

Matt King, a strategist at Citigroup,

says that foreign purchases of American

corporate debt have dried up in recent

months, and the return on investment-

grade debt so far this year has been -3.5%.

He compares the markets with a game of

musical chairs. As central banks with-

draw monetary stimulus, they are taking

seats away. Eventually someonewill miss

a seat and come downwith a bump.

Where will the next crisis occur?

The A to B of decline

Source: S&P Global

S&P Global median corporate-credit rating

1980 85 90 95 2000 05 10 15 18

B+

BB

BBB–

BBB+

A

AA–

AA+

Buttonwood

Corporate debt could be the culprit

Econom

i st.com/bl

ogs/buttonwood

erating. But the Financial Services Agency

(

FSA

), their regulator, is reluctant to put

them under too much pressure. Many pro-

vide a lifeline to ageing communities and

help prop up struggling companies.

The government thinks banks should

start offering more funding to startups and

smaller firms. It hopes that would stimu-

late economic growth more broadly, but

also thinks it would help the banks them-

selves by creating new, profitable clients.

Nudging risk-averse banks away from cal-

cified business practices while trying to

avoid a major shock to the system is a

tricky line to tread. “We want them to real-

ise that profitability is lowso their business

is not sustainable,” says an

FSA

official.

“Mergers are one option but there is still

plenty of roomfor increased productivity.”

As if all this was not hard enough, Japa-

nesebanks, like those elsewhere,must also

cope with new, low-cost competition. Chi-

na’s largest fintech company, Ant Finan-

cial, has recently set up an office in Tokyo.

Line, amessaging servicewith 75mmonth-

ly users in Japan, wants to expand into fi-

nancial services.

SBI

Sumishin, an online

bank set up by SoftBank Group and Sumi-

tomo Mitsui Trust Bank a decade ago, has

quickly become Japan’s most popular

mortgage lender, which Noriaki Maru-

yama, its president, attributes mainly to

costs that are a fifth of its lumbering rivals’.

It has shaved interest rates on home loans

to 1.17% a year, compared with an average

for major banks of 1.28%, by streamlining

operations (using artificial intelligence to

process loan applications, for instance).

MrMaruyama says the front-office clut-

ter of high-street banks can be stripped

away, leaving only cash machines. Most

transactions can be done on mobile

phones, he says. It is not an uncommon vi-

sion for a banker. But other countries do

not have such cosseted customers.

7

РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News"

VK.COM/WSNWS