The Economist

May 5th 2018

Science and technology 77

2

tion, a process that provides drinking wa-

ter for around 300m people. To do so, they

have made a membrane laced with micro-

scopic Turing patterns that can remove

salts from water up to four times faster

than commercial alternatives. Their re-

search is published thisweek in

Science

.

During desalination, seawater is often

pumped first through a porous “nanofiltra-

tion” membrane made of a substance

called polyamide. This removes bulky

ions, such as magnesium and sulphate, as

well as bacteria and other large particles.

After that, it passes through a secondmem-

brane which has even tinier pores. This

step, called reverse osmosis, removes ions

smaller than magnesium and sulphate,

particularly the sodium and chloride ions

that make up common salt and that give

seawater its characteristic taste.

The membranes employed for reverse

osmosis are rough, and so have a large sur-

face area through which water can pass.

Nanofiltration membranes, by contrast,

are smooth. That, Dr Zhang reasoned,

meant that they might be improved. To in-

troduce the necessary roughness he need-

ed some way to modify the chemical reac-

tion by which the membranes are made.

This process, known as interfacial poly-

merisation, involves two chemicals. One,

piperazine, is soluble in water. The other,

trimesoyl chloride (

TMC

), can be dissolved

only in an organic solvent such as decane,

an oily hydrocarbon.

When piperazine and

TMC

meet, they

react to form polyamide. But if the one is

dissolved in water and the other in oil,

which famously do not mix, then the reac-

tion can happen only at the surface where

the oil is floating on the water. The result is

a polyamide sheet. In practice, in industrial

conditions, this reaction is usually per-

formed on a porous support that is first

soaked in piperazine before one side is ex-

posed to

TMC

. The polyamide sheet then

forms on that side of the support. Dr

Zhang’s insightwas to see that this arrange-

ment might be modified to be the type of

two-chemical system that Turing de-

scribed in his paper—and that if it could be,

the resulting patterns would act as surface-

area-increasing bumps.

For a system to form Turing patterns,

two chemicals must diffuse at different

rates through the medium in which the re-

action is taking place. The rates cannot,

however, be too different. The ideal dis-

crepancy is about a factor often. To achieve

this, Dr Zhang added polyvinyl alcohol to

the piperazine solution, to make it more

viscous and slowpiperazine’s diffusion.

The upshot was the creation of polya-

mide sheets full of either tiny, hollow bub-

bles or interconnecting tubes, depending

on the concentration of polyvinyl alcohol

used. These are just the sorts of surface-

area-increasing features that Dr Zhang had

hoped for. And they did the job. The best

were able to handle a fourfold increase in

flowratewith no loss of performance.

Flushed with success, Dr Zhang is now

turning his attention to the reverse-osmo-

sis membranes. Though these are already

rough, he thinks he can make them

rougher. They, too, are made by interfacial

polymerisation, so he may well be able to

do so. And if both sorts of membrane can

be improved, the process of desalination,

which is likely to become more important

as demand for water increases, will be

made cheaper andmore effective.

7

F

OR the feeding of babies, everyone

agrees that “breast isbest”. It isnot, how-

ever, always convenient. Textileworkers in

Bangladesh, who are mostly women, are

entitled to four months’ maternity leave.

Once this is over, theyoften endupparking

their childrenwith relativeswhen they are

at work. Those with refrigerators at home

can use breast pumps to express milk be-

fore they go on shift, and leave it behind to

chill. But fridges are expensive, and many

do not own one. Unchilled milk goes off

within a couple of hours so the inevitable

outcome for fridgeless mothers and their

babies is the use of infant formula.

A chance meeting in a coffee shop in

Dhaka may, though, have helped with this

problem. It was between Sabrina Rasheed

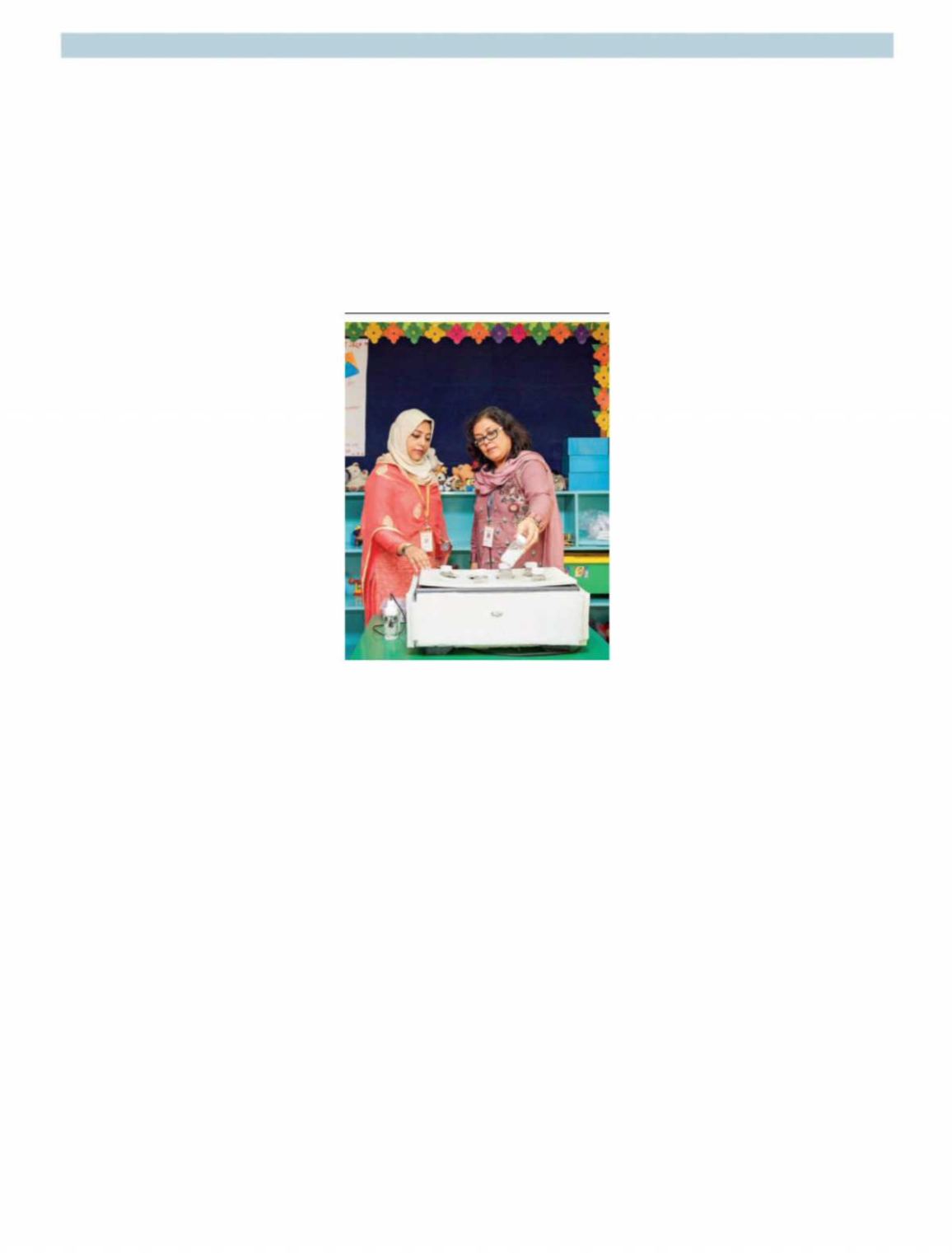

(pictured above, right), a child-nutrition ex-

pert at the International Centre for Diar-

rhoeal Disease Research in Bangladesh,

and three Canadian students. Two, Scott

Genin and Jayesh Srivastava, are engi-

neers. The third, Micaela Langille-Collins,

is a trainee doctor. The upshot of the en-

counter was that Dr Rasheed gave the stu-

dents the job of designing a low-cost, low-

techway of keepingmothers’ milkhealthy

in Bangladesh’s tropical climate, without

resorting to refrigeration.

The device the trio came up with,

shown in the picture, is a cheap pasteurisa-

tion machine based on a food warmer of

the sort used in canteens. Instead of food,

the warmer’s vessels are filled with paraf-

finwax, which is liquefied by the heat. Bot-

tles containing expressed milk, held in

bags made of silicon-coated nylon, are

hung from a plate and bathed in the wax,

which is then heated further. A thermom-

eter in the wax registers the temperature,

and once that reaches 72.5°C—the level re-

quired for pasteurisation—a timer is start-

ed. After15 seconds this sets offan alarm to

indicate that the milk has been cooked

enough to kill hostile bacteria, and the bot-

tles are removed and allowed to cool.

Thus pasteurised, microbiological tests

show, the milk’s shelf life at local room

temperatures increases from two hours to

somewhere between six and eight. This

meansno refrigeration is requiredand rela-

tives looking after babies need collect ex-

pressed milk from the factory, where the

machine is located, only once a day. The

pasteurisedmilkalso retainsmost of its nu-

tritional value.

With the aid of ten donated breast

pumps, Ms Langille-Collins and her col-

leagues tested their invention at the Inter-

fab Shirt Manufacturing workshop, north

ofDhaka. To startwith, mothers employed

there were suspicious, says Aliya Ma-

drasha, head of human resources at the

factory. That changed, though, when they

came to understand both the convenience

of the system, and the economy of no lon-

ger having to buy formulamilk.

The newmachine is also a hit with the

factory’s management. Expressing their

milk at the beginning of a shift means

women with babies suffer less discomfort

during the day, and so aremore productive.

Absenteeism among mothers has also

dropped, from five days a month to one.

The biggest benefit, though, according to

Ahasan Kabir Khan, the factory’s owner, is

the retention of skilled staff who might

otherwise leave to nurse their children.

Mr Khan is so impressed that he now

wants toput pasteurisationmachines inall

his factories. Other factoryowners, too, are

asking for the machines. Dr Rasheed and

Ms Langille-Collins are therefore develop-

ing a commercial version of the machine,

in collaboration with 10xBeta, a firm in

New York. If their patent application is ap-

proved, they plan to lease the devices to

firms all over Bangladesh and then, subse-

quently, to people in other poor countries

all around theworld.

7

Working mothers

Express delivery

Dhaka

Apasteurisationmachine forhuman

breastmilk

РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News"

VK.COM/WSNWS