32 United States

The Economist

May 5th 2018

A

NYBODY worried about America’s ability to settle political

arguments should consider the greater sage grouse. Better

still, as the May sun warms the western plains where it lives, go

andwatch it dance, as Lexington recently did inWyoming. There

are fewstranger sights in nature.

After spending the winter huddled in sage brush, a twiggy

shrub that carpets the plains and is the backdrop to a thousand

Westerns, male grouse gather on patches of open ground known

as leks. There, for several hours a day, starting at sunrise, they fan

their tail-feathers into a speckled halo and emit a peculiar war-

bling sound by dilating air-sacks in their feathery breasts. The un-

earthly chorus this makes—think of a mobile orchestra of chick-

en-sized didgeridoos—rises up from the vast and glorious

Wyoming steppe. In the lee of the snow-covered Wind River

Mountains, it is a New World Eden, an expanse of yellow and

green dottedwith distant herds of pronghorn andwild horses.

It is exceptional, however. Over half the sage brush on which

the grouse feeds has been lost and much of what remains has

been degraded by agriculture, industryand invasive grasses forti-

fied by global warming. From an estimated 16m birds, the grouse

has been reduced to fewer than 500,000 across11states. Adecade

ago this almost led to it being listed under the Endangered Spe-

ciesAct, with potentiallydisastrous consequences. Itwould have

restricted development on grouse habitat, potentially beggaring

states such asWyomingwhich collects three-fifths of its revenues

from energy companies. To prevent that, the state forged a re-

markable coalition of ranchers, hunters, conservationists, politi-

cians, scientists, miners and oilmen to devise measures to stop

the listing. Otherwestern states followed suit, and in 2015 the De-

partment of the Interior, which controls the public lands that

dominate the West, included these and some additional mea-

sures in a sweeping new management regime for the western

plains, including 98 revised land-use plans, covering 67macres of

grouse habitat. It was one of the most complicated land-manage-

ment exercises in American history, one of the biggest achieve-

ments of the Obama Interior Department. President Donald

Trump’s Interior Department may be jeopardising it.

That is not the sort of thing Secretary Ryan Zinke promised

during his confirmation grilling last year. The one-termmember

of the House of Representatives declared himself an “unapolo-

getic admirer” of Teddy Roosevelt’s conservation legacy. He also

claimed to be a devotee of the “John Muir model of wilderness”

and “Pinchot model of multiple use, using best practices”. His

subsequent record suggests that was not true. A former navy

SEAL

with an excessive fondness for saying so, Mr Zinke has

seemed mainly devoted to lekking and grousing. He has aggran-

dised himself embarrassingly, with secretarial flags, man-of-ac-

tionpublicity shots and a helicopter tour paid for fromhis depart-

ment’s firefighting budget. He has denigrated Interior’s 70,000

employees: in a speech to energy executives he said 30% were

“not loyal to the flag”. His able deputy, David Bernhardt, a former

energy lobbyist, has meanwhile attacked the large areas of con-

servation and environmental policy Interior controls.

Last month it announced plans to nobble a century-old law

protecting wild birds; it was passed a few months before the

death of Roosevelt, a keen ornithologist. Last year it eliminated

2m acres of protected area: Muir would have turned in his grave.

SowouldGifford Pinchot, because by slashing restrictions on oil-

and-gas prospectingonpublic landsMr Zinke’s department is try-

ing to trade multiple use—a public-land management principle

enshrined in law as well as tradition—for the “energy domi-

nance” demanded by President Trump.

Like the Environmental Protection Agency, Interior has also

deleted references to climate change from its literature. Given the

lead role it plays in climate science, through the

US

Geological

Survey and other research divisions, some suspect it could even

end up doing more damage to environmental policy than the

EPA

. That agency’s administrator, Scott Pruitt, seems as distracted

by personal ambition asMr Zinke, and until recently had no dep-

uty (he has filled the vacancywith a former coal lobbyist).

In this context, the review of the sage-grouse plans Mr Zinke

launched last year, which produced a list of draft revisions on

May 2nd, might seem like aminor issue. But there ismore at stake

in it than the bird.

The draft revisions suggestMr Zinkewants to promote drilling

on grouse habitat and give the statesmore say inmanaging it. The

secondaim, at least, sounds reasonable; one or twoofthe federal-

ly imposed measures seem ill-advised and western states are

fiercely independent. But there are two problemswith this.

First, putting the onus on state action risks losing sight of the

original point ofthe conservation effort, whichwas topersuade a

federal agency, the Fish andWildlife Service, not to list the grouse

as threatened. Left to themselves, the evidence suggests, states

would adopt weakermeasures, risking the feared listing.

More grouse than sage

Second, the upheaval Mr Zinke has caused is already a setback to

the collaborative, locally grounded approach to land manage-

ment that the plans, despite their federal imprimatur, represent.

Such collaborations, a quiet success ofthree previous administra-

tions, Republican and Democratic, have proliferated in the west-

ern states, especially in forests and watersheds threatened by

wildfire and drought. They are one of themost positive recent de-

velopments in American politics, a riposte to the dysfunction

partisanship has caused. But they do not happen by accident.

They require regulatory certainty—in this case, a clear sense that

the grouse will be listed failing adequate conservation mea-

sures—and a degree of mutual trust. Mr Zinke’s cynical steward-

ship ofAmerica’s public lands is eroding those conditions.

7

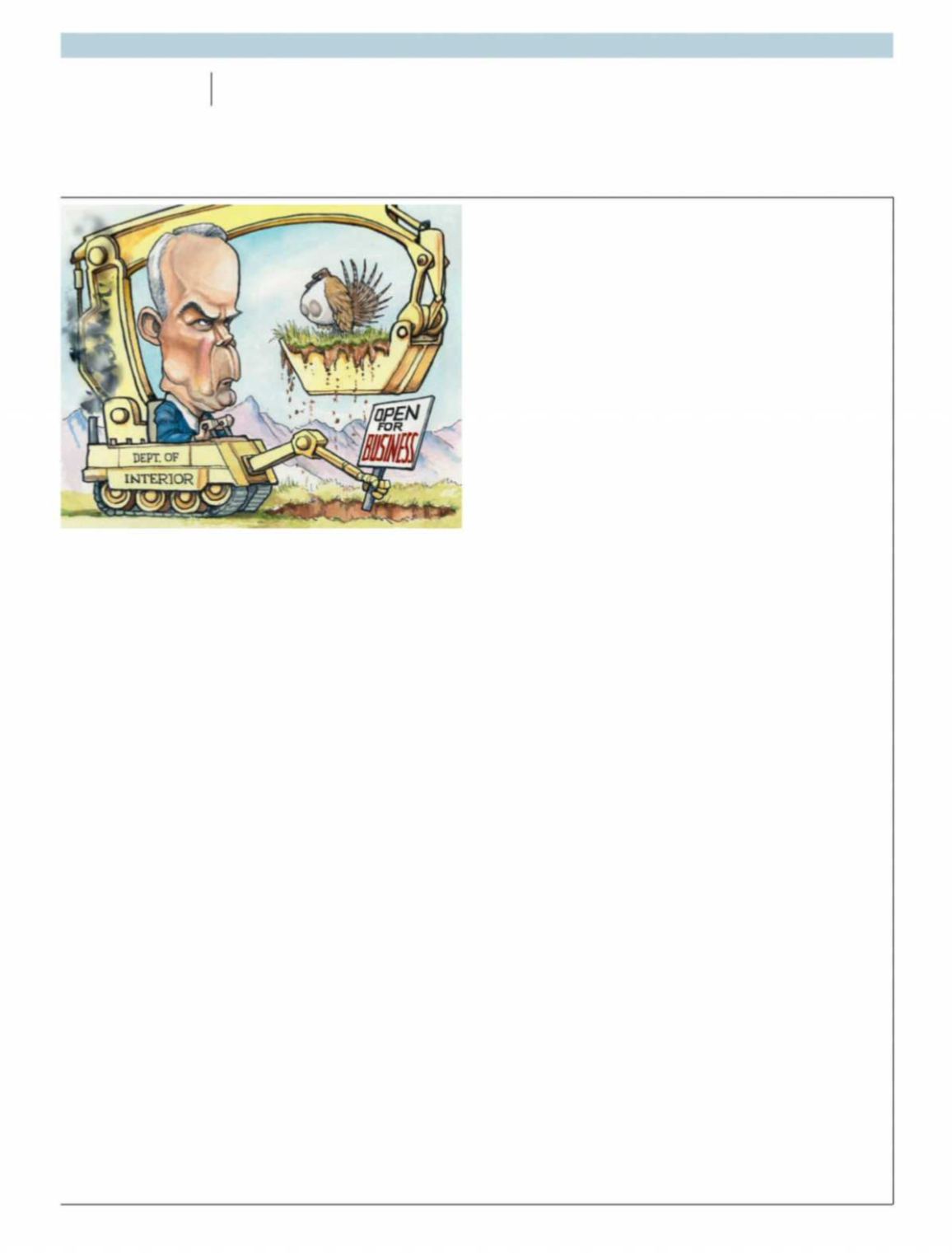

The parable of the sage grouse

Arowover an avian exhibitionist suggests howbadlyRyan Zinke is servingAmerica

Lexington

РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News"

VK.COM/WSNWS