The Economist

May 5th 2018

Briefing

Global security

23

2

anti-missile shield that Ronald Reagan pro-

posed in the 1980s, which the Soviets took

more seriously than they needed to. Such

defences couldbe verydestabilising if they

were able to deal with the diminished

forces with which an attacked adversary

might fight back. It is on that second-strike

capability that deterrence rests.

Theoretically, saysMichael O’Hanlon, a

strategist at Brookings, arms-control agree-

ments could cope with some of these wor-

ries. A New

START

follow-on could, for ex-

ample, allow each side to field an extra

offensive weapon for every ten intercep-

tors deployed by the other. He concedes

that energy weapons, if eventually shown

to be effective formore than point defence,

would be much more complicated to ac-

count for. Mr Samore, however, reckons

that anymissile-defence limitationswould

be “politically toxic” inAmerica. And ifen-

ergy weapons were to work, he says, en-

tirely newways of delivering nuclear war-

heads will be needed, such as the ones Mr

Putin is so excited about. MrMillerworries

that some in the Trump administration, for

which read Mr Bolton, may want to push

missile-defence technologies further; if

they do, the certain response from Russia

and China would be to make their war-

headsmore numerous andmore nimble.

Another big concern is cyber-weapons.

Daryl Kimball of the Arms Control Associ-

ation, a think-tank, says that cyber-attacks

on nuclear command-and-control systems

could “vastly increase crisis instability”.

Yet nobody has any good ideas about how

an arms-control agreement can cope with

such a possibility. Mr Einhorn says any

weapon that is defined by software is al-

most impossible to verify. Mr Miller sug-

gests that when it comes to cyber, deter-

rence may be the only option: “It is a

regime of self-help,” he says.

Most arms-control experts think that

the best that canbe hoped for are newtalks

with the Russians, possiblydrawing inoth-

er nuclear-weapons states, on enhancing

crisis stability, and the establishment of in-

ternational norms banning the use of

cyber in specific circumstances, such as

disabling an adversary’s strategic com-

mand-and-control systems.

A little funny in the head

Unfortunately, ifbilateral arms control is in

bad shape, so too is its multilateral equiva-

lent. The Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty,

adopted in 1996, has yet to come into force.

Three of the 44 designated “nuclear-capa-

ble states” which have to ratify it, India,

Pakistan andNorth Korea, have yet even to

sign it. Eight of the signatories, including

America, have not ratified it.

The Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty, also

first discussed in the 1990s, is in a similar

state oflimbo. Itwould seekto stop thepro-

duction of weapons-grade uranium and

plutonium by the five recognised nuclear

weapons states (America, Russia, China,

France and Britain) and the four that are

not members of the nuclear Non-Prolifera-

tion Treaty (

NPT

)—the three mentioned

above and Israel. Pakistan, though, has

been blocking negotiations on the basis

that the treaty does not deal with the large

stockpiles of uranium and plutonium that

other countries have.

The

NPT

itself remains, 50 years after it

was first signed, the bedrock multilateral

nuclear-arms control agreement. It is seen

by nearly all parties as worth preserving.

But the last reviewconference in 2015was a

fractious affair; the next one, in 2020, is

shaping up to be even worse. The gulf be-

tween the nuclear-weapon states (and

their close allies) and the rest haswidened.

The nuclear-weapon states pay lip service

to the incremental nuclear disarmament

the treaty asks of them while at the same

time modernising their forces to face the

next 50 years; this makes the nuke-nots

ever angrier.

A consequence of their frustration is

that some 130 states—about two-thirds of

the

NPT

’s membership—last year com-

bined to create, under

UN

auspices, a new

treaty on the Prohibition ofNuclearWeap-

ons (known also as the Nuclear Ban

Treaty). The nuclear-weapon states boy-

cotted the discussions leading up to the

treaty’s adoption in July, arguing that it is a

distraction from other disarmament and

non-proliferation initiatives, such as the

Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty and the

Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty. They also

have a reasonable concern that countries

might choose to move from the

NPT

to the

new treaty and thus avoid the

NPT

’s rigor-

ous safeguards against illicit fissile-materi-

al production.

A more immediate threat to the

NPT

is

the high probability that Mr Trump,

goaded byMr Bolton and his hawkish new

secretary of state, Mike Pompeo, will on

May 12th refuse to renew the presidential

waiver needed to prevent nuclear-related

sanctions on Iran from snapping back.

Should he do so, America will be in viola-

tion of the 2015 deal that curbs Iran’s nuc-

lear programme, the Joint Comprehensive

Plan of Action (

JCPOA

). The deal is be-

tween Iran and the five permanent mem-

bers of the

UN

Security Council—America,

Britain, China, France and Russia—plus

Germany. Detractors such as the president

complain that it is time-limited and that it

fails to stop Iran’s regional meddling or its

ballisticmissile programme, and that these

are fatal flaws. Israel’s prime minister, Bin-

yamin Netanyahu, eggs on such criticism.

On April 30th he made much play of evi-

dence that Iran had lied about the military

part of its nuclear programme.

This line of attack does not hold water.

Iran’s near-nuclear capabilitywas not a se-

cret: it was the reason for acting. The world

had to choosewhether to accept it as a nuc-

lear-weapon state, or one perched on the

threshold; to go to war; or to negotiate an

arms-control agreement. That agreement

is meticulously crafted for very specific

purposes: backing Iran away from the nuc-

lear threshold; blocking all its pathways to

building a nuclear device for at least ten

years; and hindering it fromdoing so there-

afterwithout being caught.

If Mr Trump pulls America out of the

deal the other parties will try to save it. But

the blow, not just to the Iran deal but to any

future attempts at multilateral arms con-

trol, could be fatal. As well as enlightened

self-interest and rigorous verification,

arms-control agreements depend on a de-

gree of trust that the parties to them will

honour their commitments even when

governments change. Persuading North

Korea to give up its nuclear weapons in re-

turn for sanctions relief and security guar-

anteeswas never very likely. PullingAmer-

ica out of the Iran deal, when there is no

evidence that Iran has broken its undertak-

ings, just a few weeks before a summit

with North Korea’s leader, Kim Jong Un,

seems certain to make it less likely still. As

Sir Lawrence says of Russia, “A degree of

trust is needed.”

Arms control, MrO’Hanlon says, “often

gets a bad rap, but it is an extraordinarily

valuable tool.” And it is one that the nuc-

lear powers risk losing through a mix of

complacency, neglect, ignorance and mal-

ice. It is within Mr Trump’s power to do

something about it. He could make a start

by holding his fire on the Iran deal while

his European allies work to meet some of

his concerns, and by indicating a willing-

ness to extend New

START

—something

which would require little more than the

stroke ofa pen. “Presidents cananddo turn

on a dime,” Ms Gottemoeller says, more in

hope than expectation. There is no sign yet

that this onewill.

7

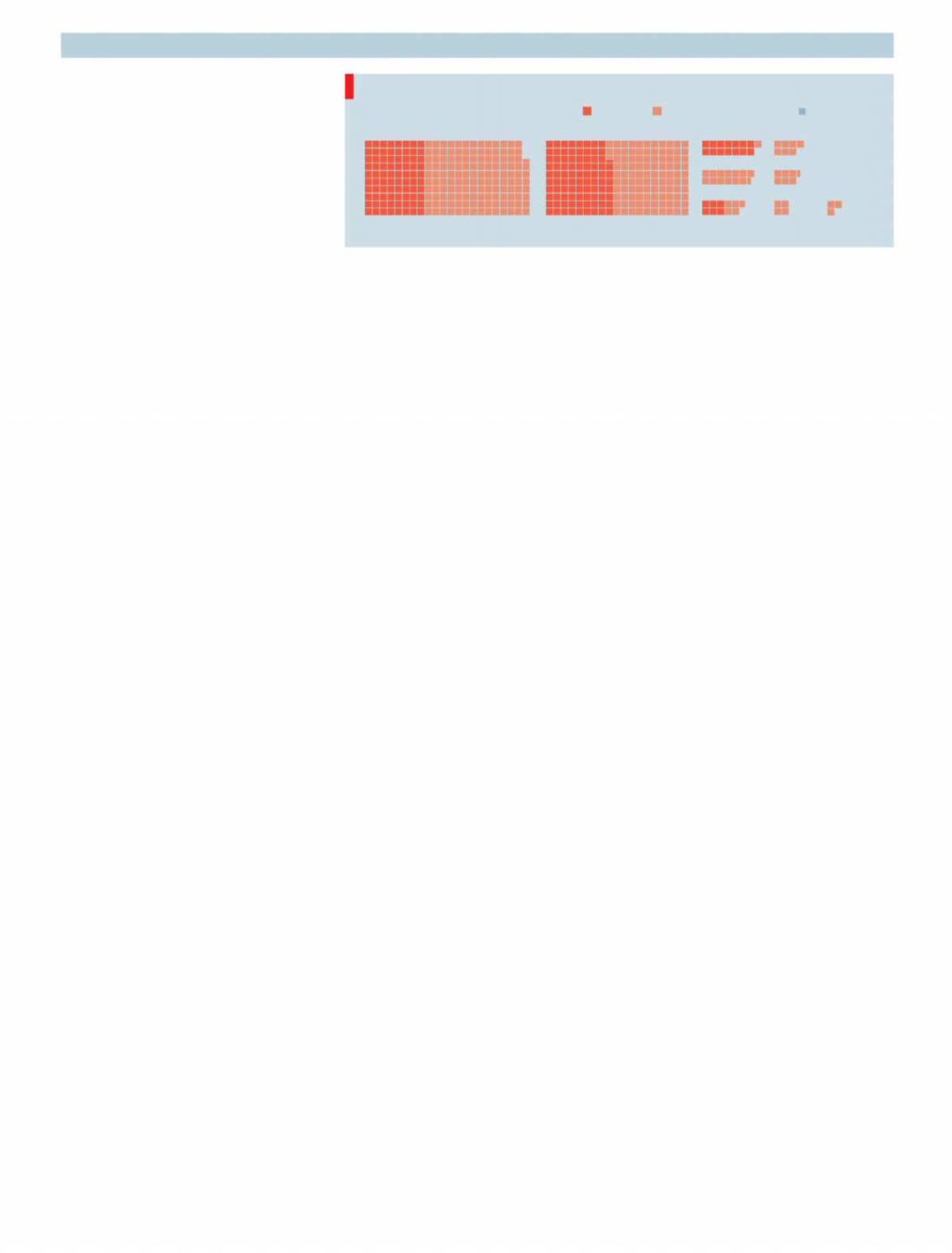

And then there were 9,345

Estimated global nuclear warheads*, 2018

Source: Federation of American Scientists

*Not including retired warheads

United States

3,800

Russia

total 4,350

France

300

China

270

Britain

215

Pakistan

130-140

India

120-130

Israel

80

North Korea

20-60

= 20 warheads

Deployed Stockpiled

РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News"

VK.COM/WSNWS