22 Briefing

Global security

The Economist

May 5th 2018

1

2

retary-general of

NATO

, informed Ameri-

ca’s allies that Russia appeared to be in vio-

lation of the Intermediate Range Nuclear

Forces (

INF

) Treaty of 1987, in which the

two superpowers agreed to give up

ground-launched nuclear weapons with

ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometres

(310 to 3,400miles). The

INF

Treatymarked

a thaw in the cold war and led to the de-

struction of 2,700missiles.

Russia’s alleged breach lies in testing

and possibly deploying a ground-

launched cruise missile, known as the

9M729

, with a range ofmore than 500 kilo-

metres. The Russians, characteristically,

deny that it can fly farther than allowed.

For their part theyhave accused theAmeri-

cans of being in breach; they say launchers

for American

SM-3

“Aegis Ashore” anti-

missile interceptors in Romania can be

used to fire prohibited cruisemissiles.

The dispute could easily be settled, says

James Acton, a nuclear-policy expert at the

Carnegie Endowment for International

Peace. If inspectors were allowed to, they

could verify the

9M729

’s range by measur-

ing its fuel tank. They could also say

whether the

SM-3

launchers are or are not

capable of launching banned weapons,

too. But the verification agreements that

were part of the

INF

have lapsed. If Ameri-

ca has suggested joint inspections, Russia

has shown nowillingness to comply.

Invalidating the policy

The Nuclear Posture Review published by

the Trump administration in February rec-

ommends trying to strong-arm Russia into

compliancewithworkon a newAmerican

ground-launched cruise missile that

would only be put into production if the

Russians continued flouting the

INF

Treaty.

Another option would be to deploy

JASSM-ER

, a new air-launched cruise mis-

sile, in Europe. Mr Einhorn is sceptical. He

believes that Russian violation was not

“casual”: “The Russians feel constrained by

INF

. Theywon’twalkthat backnow.” Gary

Samore, a former arms-control adviser to

MrObama, agrees that “The

INF

is dead.”

Many arms-control professionals would

like to preserve the

INF

because the weap-

ons it eliminated from Europe were inher-

ently destabilising. But it is not just the

Russians who are chafing under its restric-

tions. Jim Miller, a former under-secretary

of defence, thinks the

INF

Treaty is worth

saving. But he concedes that, having seen

China andNorthKorea build large ground-

launched intermediate-range nuclear mis-

sile forces, some will argue for deploying

similar systems from bases in the Pacific,

such as Guam.

One such is John Bolton, Mr Trump’s

new national security adviser. In 2011 Mr

Bolton wrote a

Wall Street Journal

op-ed

which called for either “multilateralising”

the

INF

—that is, getting other countries to

abide by its strictures—or abandoning it.

The Russians have suggested something

very similar. Like Mr Bolton they are being

disingenuous: multilateralising the agree-

ment is an impossible goal.

Nor is Mr Bolton much of a fan of New

START

. He fought hard to prevent its ratifi-

cation, describing it as a formof “unilateral

disarmament”. His main concern was the

limitation on delivery systems, such as

submarine-launched ballistic missiles. He

believed this would “cripple” a concept

known as “prompt global strike”, in which

such missiles were to be used for very pre-

cise non-nuclear bombardments of any

point on Earth, however distant and how-

everwell defended.

Mr Bolton compared New

START

unfa-

vourably with the 2002 Treaty of Moscow

(also known as

SORT

—the Strategic Offen-

sive Reductions Treaty), the treaty’s super-

sededpredecessor, whichhe hadhelped to

negotiate. Seen without the benefit of pro-

genitive pride, though,

SORT

is not much

cop. It had nomonitoring or verification re-

gime. It did nothing about launchers, and

the warheads it eliminated needed only to

be mothballed, not destroyed. It would be

harsh to say that

SORT

was hardly worth

the paper it was written on. But it is telling

that not much of that paper was required.

The detailed provisions of

START I

, signed

in 1991, and New

START

both made good-

sized books:

SORT

barely filled two pages.

Mr Bolton at least knows what New

START

is. It is less clear that his boss does. In

a call between them in early 2017, Mr Putin

sounded Mr Trump out on extending the

agreement. Pausing to ask aides what Mr

Putin was talking about, Mr Trump came

back on the phone to declare that it was

just one of several terrible deals negotiated

by his predecessor, so probably not.

His administration is not dead against

extension. The Nuclear Posture Review is

guardedly non-committal about it. Losing

the insights into its opponent’s strategic

forces provided by the treaty’s verification

regime would be a serious setback for the

Pentagon—as it would for its Russian coun-

terparts. But the odds on extension are

lengthening. Sir Lawrence Freedman, a

British nuclear strategist, argues that arms

control tends to follow rather than lead

politics. “Adegree oftrust isneeded. Unfor-

tunately, the Russians don’t seem able to

tell the truth anymore.”

If arms control does indeed followpoli-

tics, could better relations between the big

nuclear powers, at some later date, re-ener-

gise arms control? Alas, probably not. The

problem is potentially destabilising tech-

nologies, notably those of missile defence

and cyberwarfare.

Condemning awhole programme

In 1972 America and the Soviet Union

signed the Anti Ballistic Missile Treaty. It

limited the defences both sides could em-

ploy so that theywould remainvulnerable

to a counter-attack, thus assuring contin-

ued deterrence. In 2002, when Mr Bolton

was, improbably, under-secretary for arms

control at the State Department, America

withdrew from the treaty so that it could

deploy defences designed to protect the

homeland from limited attacks, a project

on which it has spent $40bn so far, to un-

certain effect. Work on the exotic weapons

Mr Putin bragged about in his recent “Dr

Strangelove” speech started shortly there-

after. The “boost-glide” system which

would allow an incoming weapon to fly

and manoeuvre, rather than just fall; the

cruise missile with an intercontinental

range; and the nuclear-armed long-range

underwater vehicle are all designed to de-

feat future Americanmissile defences.

Russia has never believedAmerica’s as-

surances that its national anti-missile sys-

tem is intended solely to guard against a

limited attack from the likes of Iran and

North Korea. It also claims to believe that

more modest “theatre” systems, like the

SM-3

s in Romania, could be used to lessen

the deterrent power of its own missiles—a

stance that China echoes. Both countries

fear further advances in American missile

defence, brought about either by more ca-

pable interceptors or, just conceivably, di-

rected-energy weapons that zap their tar-

gets from a distance using microwaves or

laser beams—a feature of the “Star Wars”

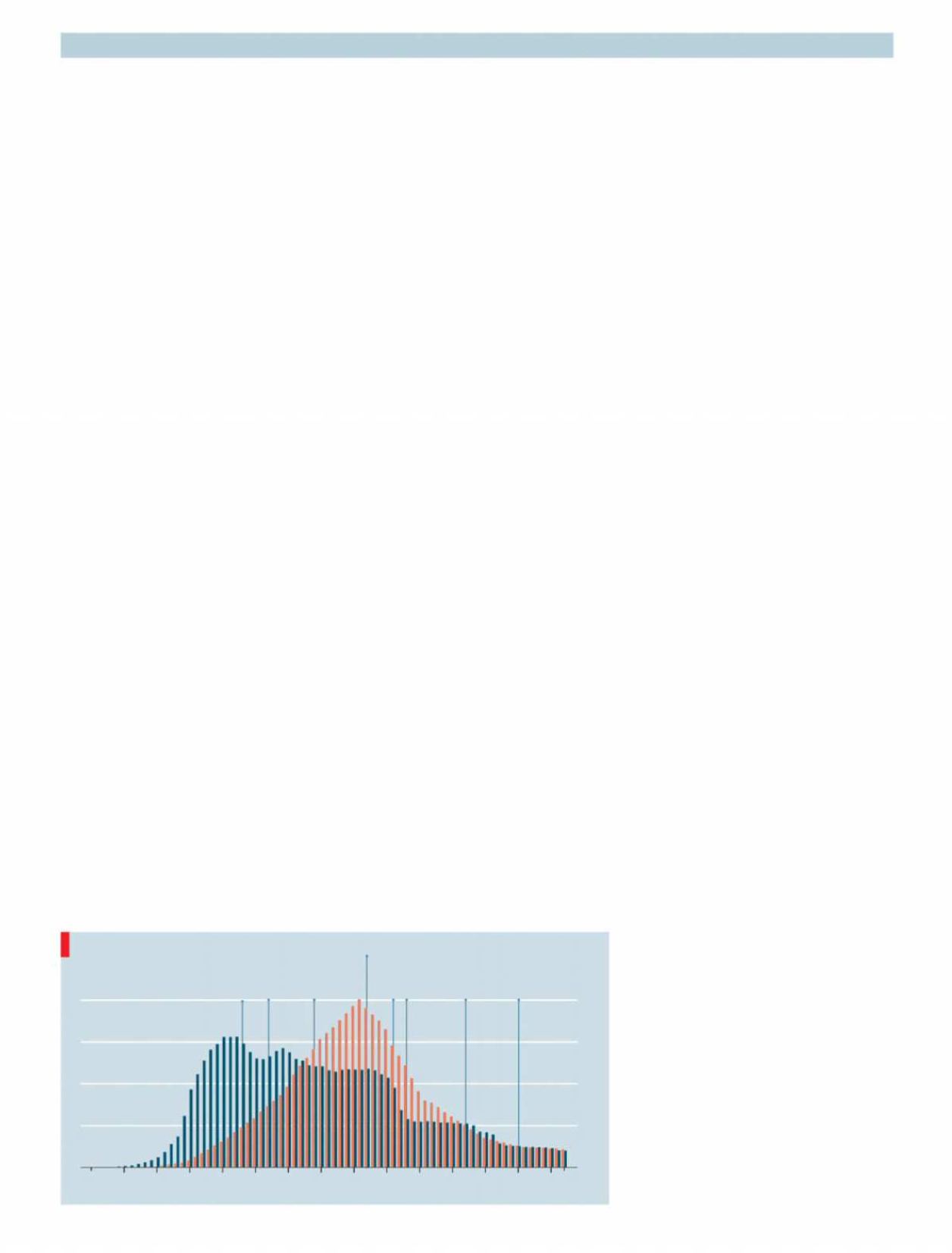

It was a START

Source: Federation of American Scientists

Nuclear warhead inventories, ’000

0

10

20

30

40

1945 50 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95 2000 05 10

17

United

States

Soviet

Union/

Russia

1987 Intermediate-Range

Nuclear Forces Treaty

1991

START I

1972

SALT I

1979

SALT II

1968 Non-Proliferation Treaty

1993

START II

2002

SORT

2010

New START

РЕЛИЗ ПОДГОТОВИЛА ГРУППА "What's News"

VK.COM/WSNWS