53

Bloomberg Businessweek

May 14, 2018

“There are people in history who have no ideology and

adapt to circumstances,” says Geney Torruco, who serves as

the oicial historian of Tabasco’s capital city, Villahermosa.

Such people, he says, have almost nothing in common with

López Obrador. Rodolfo Lara, his middle school teacher,

describes someone whose leftist beliefs have never really

changed, even if his method of expressing them has evolved.

“He’s matured in the sense that his expressions aren’t as

harsh. He invokes ‘love and peace’ whenever they try to

corner him. But has he changed his ideology? I don’t think

so,” Lara says.

In 1988, López Obrador joined a coalition of leftist parties,

ran for governor, and lost by a wide margin, which didn’t stop

him from leading protests claiming voter fraud. He lost a bid

for governor again in 1994, and this time his complaints of

vote-rigging carried more weight. Regulators found evidence

of numerous discrepancies at polling stations. He led a cara-

van of protesters from Tabasco to Mexico City, where he and

his followers took over the capital’s main square. The sit-in was

eventually broken up, but not before it helped force the resig-

nation of Mexico’s interior minister, who serves as the presi-

dent’s second-in-command.

López Obrador now was a presence on the national stage,

and his leadership of a string of protests against Pemex, the

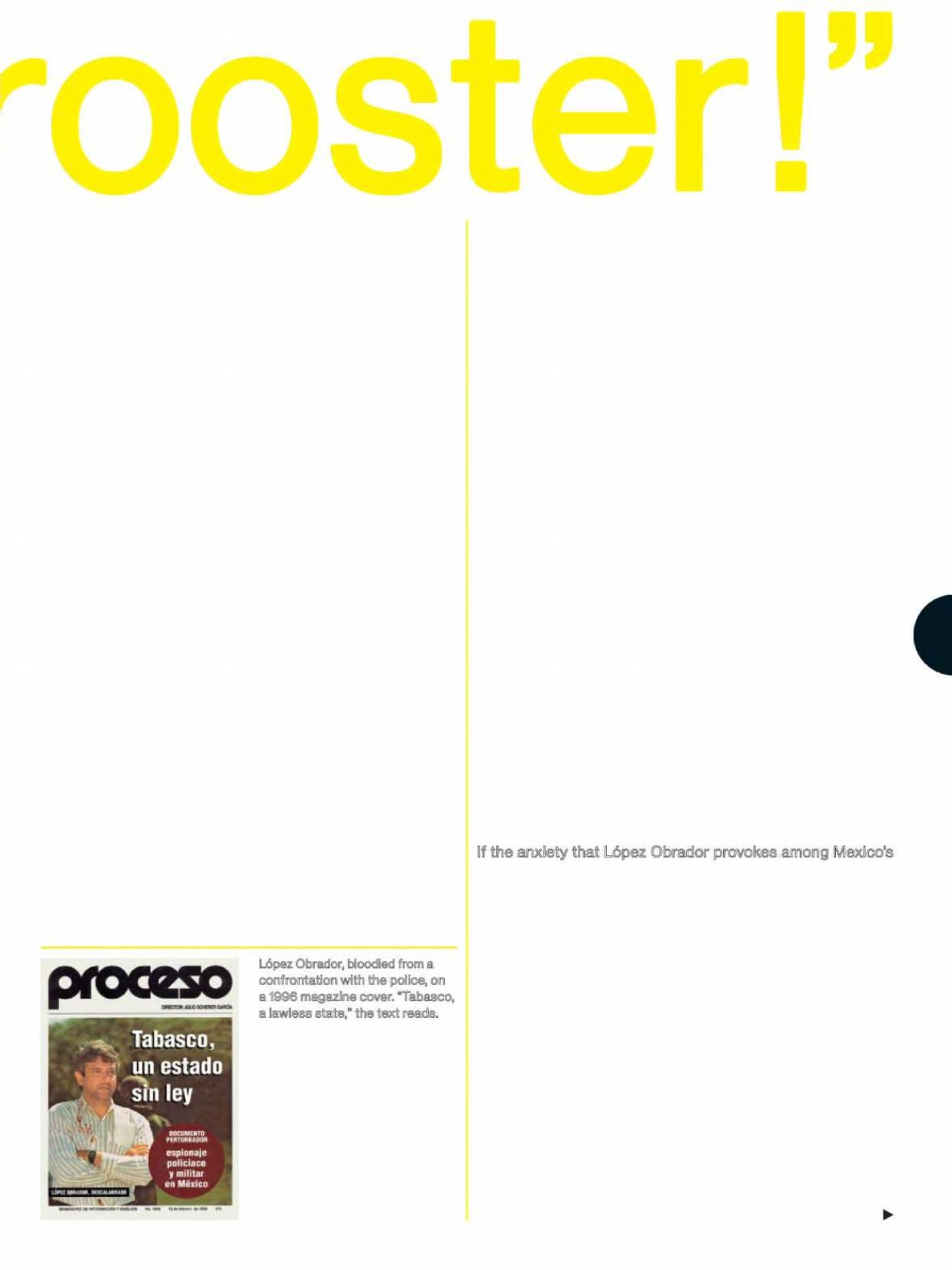

national oil company, helped him stay there. In 1996, Mexican

police tried to remove him from one such blockade. Pictures

of him in a blood-soaked shirt graced the cover of a national

magazine, reinforcing his standing as one of the country’s most

persistent social agitators.

All of this set the stage for his irst—and, to date, only—

electoral victory. In 2000 he was elected mayor of Mexico

City. He instituted a slate of social programs, including

monthly pensions for the elderly, and ushered in wide-

spread infrastructure improvements. As his popularity grew,

his political opponents closed in on him. Amid accusations

that he improperly built a road to a hospital on private land,

he was impeached. The case buckled under scrutiny and

under pressure from protests that attracted more than 1 mil-

lion supporters. Mexico’s attorney general, who was widely

accused of trying to sabotage López Obrador’s presidential

aspirations, was forced out of oice. López Obrador ended

his term in 2005 with approval ratings hovering around

80 percent.

During his irst presidential campaign, as the candidate of

the Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD) in 2006, he was

often cast in the media as a member of Latin America’s New

Left, a group that included populists such as Venezuela’s

Hugo Chávez and Argentina’s Néstor Kirchner. But Mexico’s

politics have always been more intricately connected to the

country’s northern neighbors than its southern ones, and it

narrowly resisted the leftward swing. López Obrador lost to

Felipe Calderón by about a half-percentage point. He disputed

the results, again alleging fraud and casting himself as a polit-

ical threat that Mexico’s elite would do anything to destroy.

His followers took over tollbooths on federal highways and

surrounded the oices of foreign banks, accusing the busi-

nesses of conspiring with Calderón to deny him his rightful tri-

umph. López Obrador declared himself the legitimate winner

and appointed members to a shadow cabinet. He led another

sit-in in downtown Mexico City, and this one lasted more than

a month.

By the time he lost his second presidential bid, in 2012, his

reputation among rivals was irmly set, and it centers on two

dominant traits: a seeming willingness to tear down any insti-

tution he believes is biased against his political movement and

a bitter reluctance, regardless of the circumstances, to give up.

If the anxiety that López Obrador provokes among Mexico’s

political and business leadership has a geographical cen-

ter, it probably sits somewhere near Monterrey. Many of

the country’s most successful international corporations are

headquartered in the city, which has been thoroughly trans-

formed during the past 25 years by Nafta. Factories and busi-

ness parks ring the outskirts, and its roadsides are crowded

with chains: Carl’s Jr., 7-Eleven, Walmart. Monterrey isn’t

immune to Mexico’s epidemic of cartel violence, but some of

the suburbs on the west end of town could be mistaken for

upscale neighborhoods in Southern California. The region

has the country’s lowest poverty rate and highest formal

employment rate, and a per capita income roughly double

the national average.

When Trump hectored Carrier Corp. to keep manufactur-

ing jobs at a plant in Indianapolis during the 2016 campaign,

those jobs came here anyway, to a sprawling complex of

factories and warehouses north of town. And when Trump

swore of Oreos because Nabisco started talking about

López Obrador, bloodied from a

confrontation with the police, on

a 1996 magazine cover. “Tabasco,

a lawless state,” the text reads.