54

Bloomberg Businessweek

May 14, 2018

moving out of Chicago, those jobs, too, ended up in the

same industrial park.

The development is called Interpuerto Monterrey, a

3,459-acre complex that opened in 2013 and is now home to

a dozen companies from the U.S., Korea, Japan, and Mexico.

Its enticements are clear: easy access to Mexico’s two main

rail lines, a dedicated customs oice, full utility services, a

two-hour drive to the border, and a seemingly inexhaustible

supply of cheap labor. That said, these can be challenging

times. In 2017 the park attracted a little more than half of

the $120 million in investment it had forecast that February.

Chief Executive Oicer Mauricio Garza Kalifa blames it on a

“perfect storm” of uncertainty that’s settled over Monterrey.

The ongoing Nafta renegotiation is part of it. So is the new

U.S. corporate tax plan, which has bitten into Mexico’s com-

petitive advantages. Finally, there’s López Obrador.

“Yes, there is a little bit of worry around what, in reality,

he’s actually going to do,” Garza Kalifa says. “Is he going to rad-

ically change the course of the country, or will he follow the

same general path we’ve been on? Foreign investors seem cau-

tious, waiting to see what’s going to happen.”

Mexico’s domestic investors are also skittish. In

Monterrey’s executive suites, there’s a natural antago-

nism toward López Obrador. Some suspect it’s them he’s

talking about when he rails against the “maia of power.”

In February the candidate visited the city and convened a

meeting at a Holiday Inn Express, ostensibly to assure the

business community that he was willing to work with them.

Hundreds crammed into the conference hall, but some who

attended say the gathering was notable for who wasn’t there.

Jesus Garza, who runs a Monterrey inancial company and

who previously worked as an economist for Mexico’s Central

Bank and the Ministry of Finance, says many of the city’s

biggest business leaders were nowhere to be seen.

Garza managed to snag an invitation from a friend involved

with López Obrador’s political party, Morena. Like many oth-

ers here, he was keen to hear what López Obrador had to say

about the energy sector. For most of a century, Pemex domi-

nated the industry. But in 2013 the government opened the oil

and gas business to foreign companies. The idea that López

Obrador might nullify many of those contracts, undermining

the sector’s privatization plan, tops the list of concerns among

many business leaders.

López Obrador has said he has no plans to nullify any of

the contracts, which are valued at as much as $153 billion—

unless reviews prove individual contracts were tainted by cor-

ruption. A week before that February meeting, one of López

Obrador’s economic advisers publicly assured investors that

they shouldn’t be scared and that the contracts would be

respected and protected. Even if López Obrador wanted to

roll back the reform, he’d need the support of two-thirds of

Congress. But when López Obrador got to Monterrey, Garza

says, the candidate seemed to leave the door open to a massive

overhaul of the sector. “I think deep down inside he doesn’t

believe in the energy reform agenda that was established by

the current administration,” Garza says. “And with power, I

think he would reverse it if he got the chance.”

That sort of distrust casts a shadow over almost everything

López Obrador promises. Some warn that his history of dis-

puting election results is a sign of authoritarian impulses, and

they warn he might bring a Hugo Chávez-style socialism to the

country. That typically means government spending. López

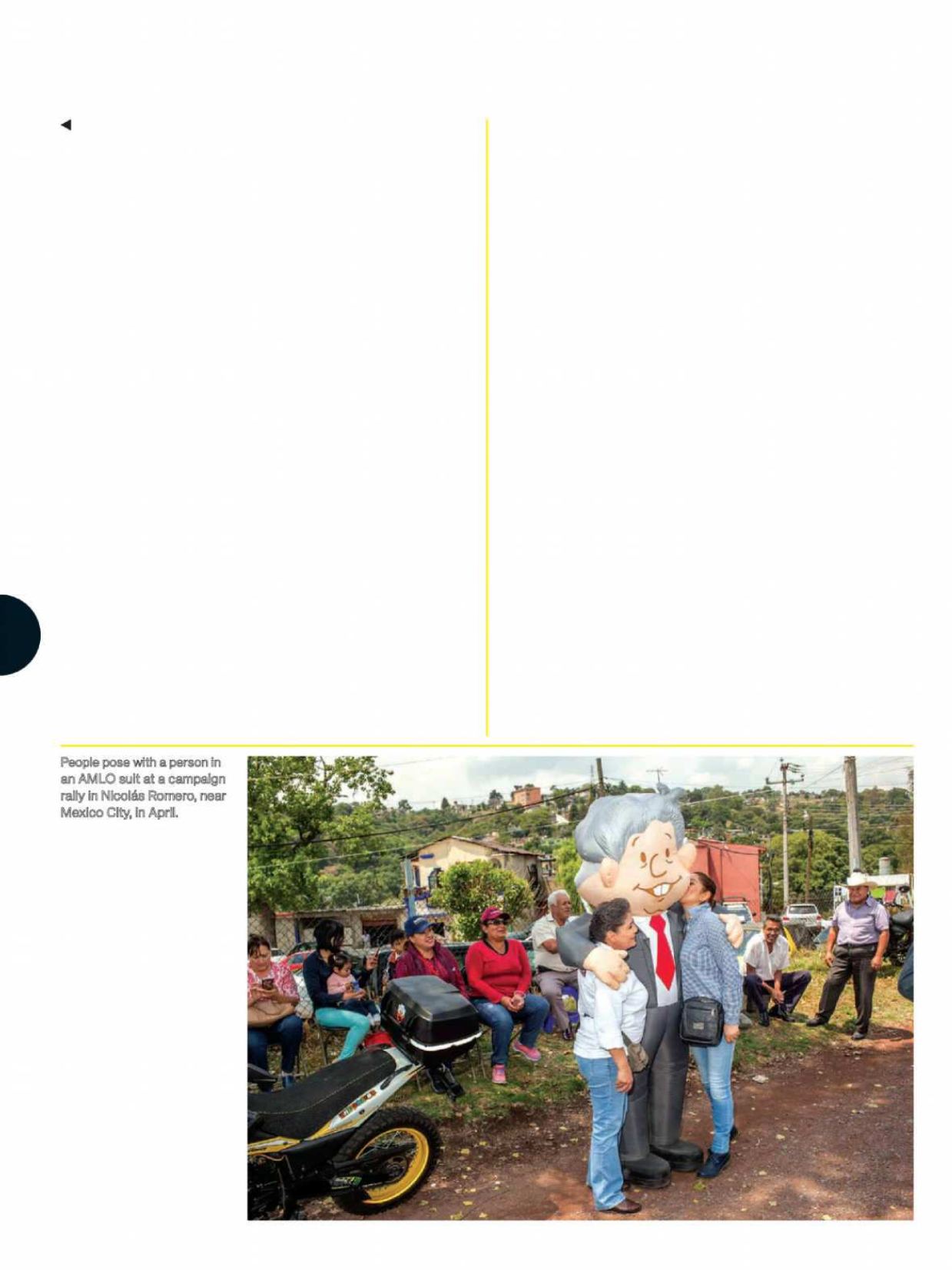

People pose with a person in

an AMLO suit at a campaign

rally in Nicolás Romero, near

Mexico City, in April.