TECHNOLOGY

Bloomberg Businessweek

May 14, 2018

2

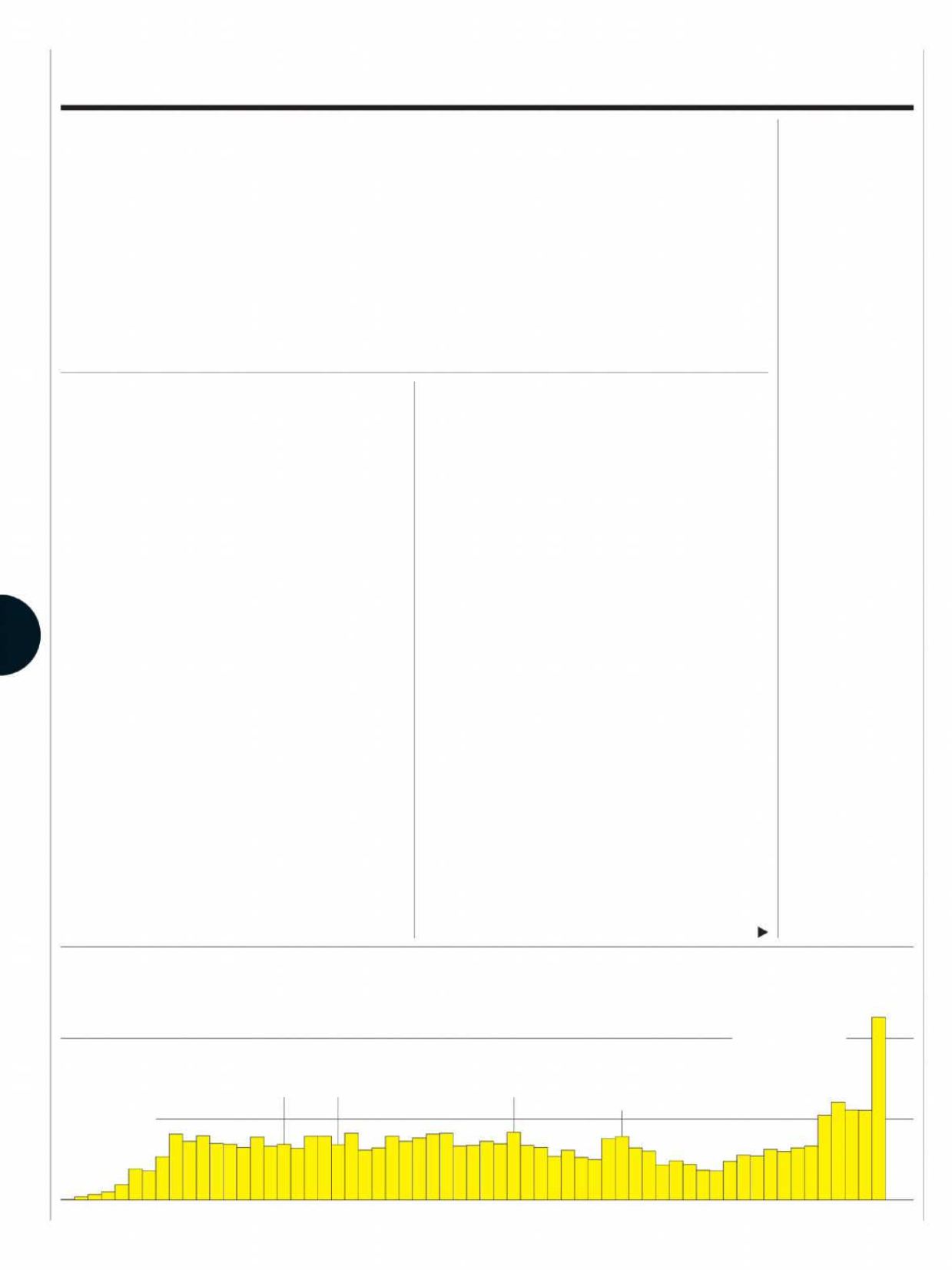

Soviet Sputnik

satellites made it

into space in 1957

400

200

0

26

DATA:UNITED NATIONS OFFICE FOR OUTER SPACE AFFAIRS

In the race to commercialize space, one premise

is undisputed: It’s getting crowded up there. From

private enterprise to universities to the military,

everyone has an eye on the sky as it comes inan-

cially within reach. Yet it’s not clear how all these

new orbital gadgets will coexist, zipping around the

planet as fast as 17,500 mph, navigating a mineield

of debris from earlier space ventures.

Aerospace Corp., a federally funded research cen-

ter, has a suggestion: Stick a small, quarter-pound

GPS transponder on each craft for tracking, ID, and

oversight. Common in civil aviation and maritime

navigation, transponders have never made it widely

to low-Earth orbit. Satellite tracking consists mostly

of ground-based radar and telescopes.

Humankind has launched some 7,500 satel-

lites since the dawn of the Space Age, with more

than 1,500 still active. Companies including LeoSat

Enterprises, OneWeb, Planet Labs, and Elon Musk’s

SpaceX plan to put at least 20,000 more in orbit.

Defunct satellites often burn up in the atmos-

phere, while larger craft are sent to their doom in

a remote area of the South Paciic. Others are lown

farther into space, to an orbital graveyard. The irst

decades of spacefaring “relied upon the ‘big sky’

approach to avoiding orbital crashes,” says Andrew

Abraham, a senior researcher and engineer at

Aerospace. “The assumption was that the volume of

space is too large compared with the volume occu-

pied by man-made objects.” That approach, how-

ever, is becoming dated.

Spent satellites, or pieces of them, become hyper-

sonic space lotsam. One catastrophic incident,

such as the 2009 collision of a U.S. satellite with a

dead Russian craft, can mean disaster not only for

the company involved but also for other operators.

New debris increases uncertainty and requires quick

assessments to determine who needs to move out of

the way and how fast. The 2009 accident, coupled

with China’s deliberate destruction of a weather

satellite two years earlier, account for more than

one-third of all the space junk in low-Earth orbit,

according to a 2011 NASA study.

With each collision comes more debris—and

more risk for any multimillion-dollar orbiting

object. Today, satellite operators must manage

these potential disasters (known in the industry

as “conjunctions”) every month or two, but soon

they’ll become routine, Abraham says.

The U.S. Joint Space Operations Center, which

tracks about 22,000 objects in orbit, issued

1.2 million collision warnings in 2016, prompting

148 avoidance maneuvers. Usually the warnings

come about ive to seven days before a potential

collision, according to retired U.S. Navy Admiral

Cecil Haney, an Aerospace senior adviser

1957

2017

Orbital Obstacle Course

Objects launched into space, by year

○ As space gets more crowded, tiny transponders could help satellites avoid crashes

Air Tra cControl,

Without theAir

453

objects went up

in 2017, more than

double 2016’s total

Skylab space

station, 1973

Milestone launches ⊲

Voyager 1 space

probe, 1977

Hubble Space

Telescope, 1990

First module of the

International Space

Station, 1998