BUSINESS

Bloomberg Businessweek

May 14, 2018

23

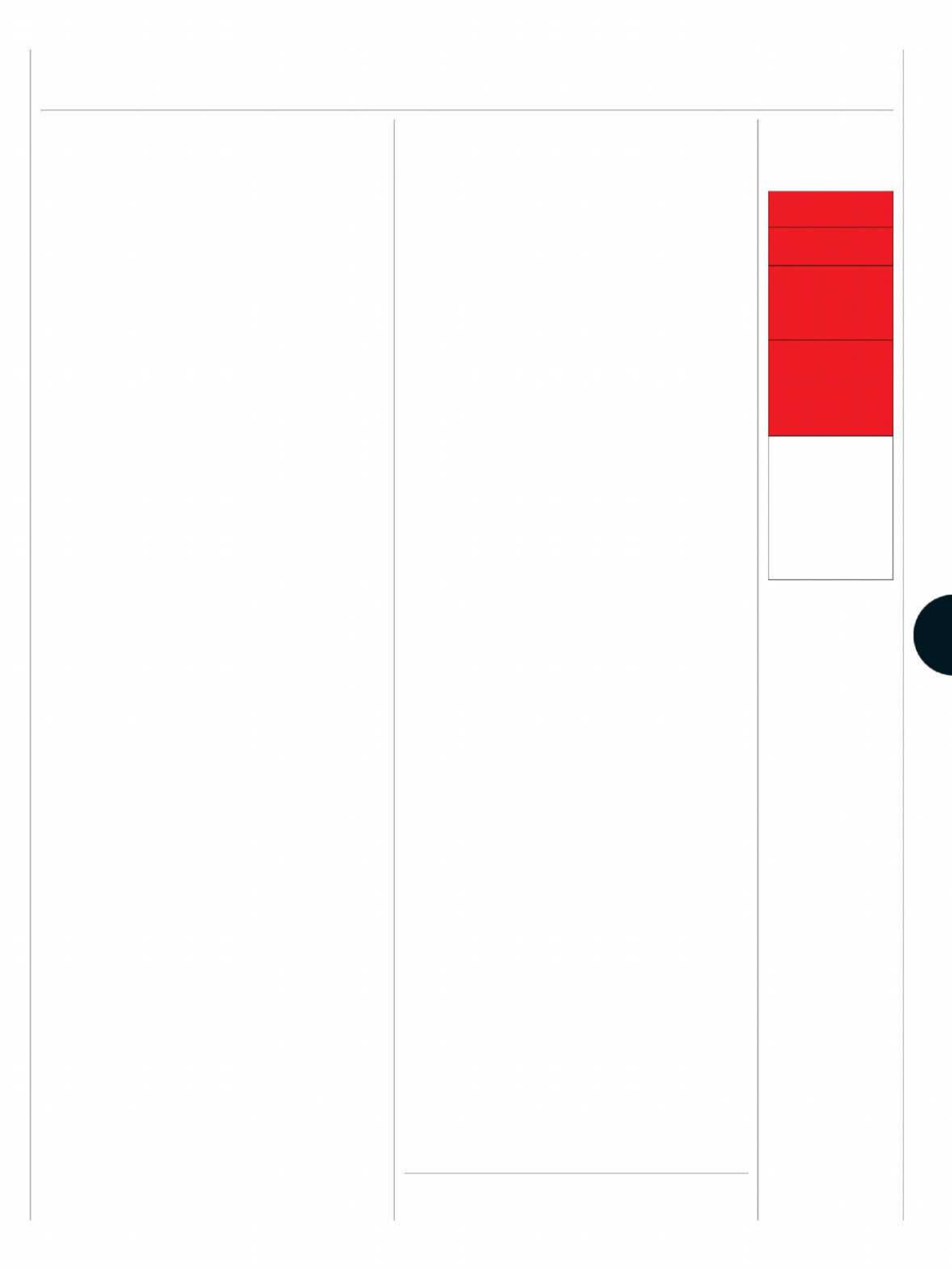

ILLUSTRATION BY VIKTOR HACHMANG. DATA: WORKPLACE BULLYING INSTITUTE

THE BOTTOM LINE Nike’s marketing positioned the company as

a promoter of self-expression and equality. But former employees

say it allowed a culture of workplace bullying to flourish.

statement. “Whenwe discover issues, we take action.”

Nike also provided Bloomberg with the tran-

script of a town hall Parker held on May 3, in which

he vowed the environment will change. “We all

have an obligation—and it’s non-negotiable—to cre-

ate and cultivate an environment of respect and

inclusion,” he told employees. “And that starts

with me. I apologize to the people on our team

who were excluded.…We’re going to move from a

place where the loudest voices carry the conversa-

tion to [one where] every voice is heard.”

The company declined to make Edwards avail-

able for an interview. He’s acting as an adviser to

Parker until he retires in August, when he’ll receive

a $525,000 payout, according to public ilings.

Nike says it’s reviewing how it deals with com-

plaints, redesigning management training, and

beginning unconscious bias awareness education

for employees this year. It’s also vowed to promote

more women and minorities into leadership roles.

Currently, managers are 38 percent women and

23 percent nonwhite.

Workplace bullying is often deined as behavior—

including verbal abuse, derogatory remarks, humil-

iation, and undermining work performance—that

results in physical or mental harm. About 1 in 5

Americans say they’ve been the target of it, accord-

ing to a 2017 survey by Zogby Analytics that was

commissioned by the Workplace Bullying Institute.

Men make up 70 percent of the perpetrators and

34 percent of the targets. “It’s a signiicant and still

underreported problem,” Yamada says. Surveys

have shown such behavior is four times more prev-

alent than legally actionable sexual harassment, he

says. “Bullying looms large.”

Ironically, Nike is one of the minority of compa-

nies that has a formal antiharassment policy that

calls out bullying behavior such as verbal abuse,

intimidation, humiliation, and retaliation, accord-

ing to a copy obtained by Bloomberg. It also notes

that harassment not based on a legally protected

characteristic, such as gender or race, can still vio-

late company rules.

One reason few companies have speciic anti-

bullying policies is that there aren’t federal or state

laws in the U.S. outlawing the behavior, which

makes America a laggard when compared with

Western Europe, Canada, and Australia.

A lack of legal protections greatly reduces the

possibility of liability for employers. It’s diicult to

bring a lawsuit based on bullying, and businesses

have worked to keep it that way. Over the past

decade, antibullying bills were introduced in about

30 states, but they’ve all been defeated after oppo-

sition from corporate lobbying groups, Yamada

says. A workplace bullying bill is gaining sponsors

in Massachusetts’ legislature, but its future is uncer-

tain. If there were antibullying laws, companies

would be liable and do more to deter the practice,

according to Namie. “It’s the only form of abuse

that hasn’t been addressed by law,” he says. “It goes

beyond gender to ‘I’m powerful, I can do any damn

thing I want.’ ”

When executives feel entitled or untouchable,

that often leads to bullying and then to other inap-

propriate behavior, Yamada says. In many of the

workplace environments that resulted in some of

the high-proile #MeToo moments, such as that at

Weinstein Co., an “undercurrent” of bullying cre-

ated a belief that mistreatment would go unpun-

ished, he says. “It’s that bullying atmosphere that

helps to enable and empower sexual harassment.”

According to the former Nike employees, the lack

of a fear of reprisal created an environment where

male executives, many married, could pursue and

have sexual relationships with subordinates and

assistants—behavior Nike says it tries to prevent but

doesn’t prohibit. Many times the careers of those

involved were unafected, which only normalized

the behavior, they say. And when there were reper-

cussions, the men received little if any punishment,

while women often faced consequences. In one

instance several years ago, they say, an executive

was caught having sex with his assistant on a confer-

ence table. He wasn’t disciplined, some of the peo-

ple say, but the woman was reassigned.

Several former female employees describe simi-

lar experiences of encountering several slights and

ofenses—not one egregious incident—that increased

as they moved up the ladder. One woman says her

boss, a senior director, had derogatory nicknames

for female stafers and would overtly favor men

on the team with better opportunities. A former

female manager says a male colleague had multiple

complaints of bullying made against him to human

resources, but the only punishment meted out was

a delayed promotion. Eventually, frustration with

Nike’s handling of such incidents persuaded several

women to leave the company, they say.

The situation was particularly galling to employ-

ees who’d been drawn to Nike because of its cool

and progressive reputation, burnished by such

advertising slogans as “If You Let Me Play” and its

T-shirts adorned simply with the word “equality.”

“We always wished the company would live up to

its marketing,” says one former female executive.

“But it didn’t.”

—Matt Townsend and Esmé E. Deprez

○ Share of respondents

to a 2017 survey of

workplace bullying

who report:

37%

Unaware of bullying

at their workplace

25%

Aware of bullying at

their workplace but

haven’t experienced

or witnessed it

19%

Witnessed bullying

10%

Have been bullied

9%

Currently bullied