BUSINESS

Bloomberg Businessweek

May 14, 2018

20

OPENING SPREAD:PHOTOGRAPH BY JALAL ABUTHINA FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK.DATA:BP

Behind the 65-story glass tower that houses the

shiny new headquarters of Abu Dhabi National

Oil Co. sits a remnant of the Middle Eastern emir-

ate’s not-so-distant past: the squat, sand-colored

building that the government-owned energy giant

once called home.

The stark contrast between the old and new

buildings provides a hint of the changes afoot in

energy-rich Abu Dhabi. The tiny, but stratospher-

ically wealthy, emirate is trying to forge an econ-

omy for a post-oil world and needs to wring more

proits from its petroleum industry to inance

the makeover.

A similar shift is taking place in neighboring

Saudi Arabia, where Adnoc’s larger rival, Saudi

Aramco, plans to sell shares for the irst time. With

a projected $2 trillion valuation, Aramco is set to

have the world’s biggest initial public ofering.

Adnoc also wants to secure an economic future for

its government owner after the hydrocarbons run

out, but it’s treading a diferent path. “Adnoc has

always been seen as a stodgy, slow-moving com-

pany,” says Robin Mills, chief executive oicer of

consultant Qamar Energy. “Now they’re striving

to set up a strategy and actually implement it. It’s

still a work in progress.”

The man in charge of revamping Adnoc and

managing its 50,000 employees is Sultan Al Jaber,

who became CEO in 2016. His efort has an exis-

tential urgency, because Abu Dhabi—like Saudi

Arabia—ofers something the world apparently

has too much of: oil. The boom irst fell in 2014,

when the price of crude plunged by more than

half, breaking a string of $100-per-barrel years

that had engorged budgets and bred complacency

across the Gulf.

Since 2017, the United Arab Emirates, of which

Abu Dhabi is the capital, has taken part in the

Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries

program to constrain output to prop up prices.

Now—even as it’s limiting Adnoc’s revenue to sat-

isfy OPEC—it’s also revamping the national oil

giant and pitching the company to foreign inves-

tors to tap the capital and technology needed for

its transformation.

“What became evident in 2014 and 2015 was

the fact that the energy market is no longer what

it used to be,” Al Jaber says. “You can no longer be

dependent on only oil prices. Adnoc had to come

to terms with the realities on the ground.”

Since its founding in 1971, Adnoc has been syn-

onymous with the oil wealth that thrust the U.A.E.

into modernity. It’s the company that made pos-

sible Abu Dhabi’s glittering cityscape. It helped

keep the lights on for Dubai, too: Abu Dhabi bailed

out its lashier neighbor after the 2008 inancial

crisis, and an Abu Dhabi-owned pipeline supplies

the natural gas Dubai needs every day to keep its

shopping malls and hotels bright and cool.

For much of its ive-decade history, Adnoc has

sold crude to the mostly Western companies that

help pump it, or to traders that lipped their cargo

for proit in Asia or the Mediterranean. Reiners in

those countries turned that oil into gasoline and

diesel or feedstock for chemical plants to produce

plastics and other petroleum derivatives.

But talk in the global energy markets has

moved from peak oil—concern that reserves were

doomed to run out—to peak demand—forecasts of

continuing oversupply. Oil producers are being

bufeted by declining prices and uncertainty over

the future direction of their business.

So Abu Dhabi has decided to build a hedge

against the shifting energy market by pushing

Adnoc to get involved in the entire supply chain,

alongside the oil majors and traders. The hope

is that by dangling access to the emirate’s oil

reserves—the U.A.E. has about 6 percent of the

world’s crude—Adnoc can bring in the funds and

expertise that will help contribute to the broader

national economy.

“Abu Dhabi is reinvesting for development and

to expand the economy,” says Hootan Yazhari,

Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s chief Middle East

markets analyst. “The question of whether there

is urgency to do this depends on your view of oil.

By 2030, oil is unlikely to be where it is today.”

In an efort to ensure Adnoc has long-term buy-

ers for all its oil, Abu Dhabi over the past two years

let Chinese and Indian companies participate in its

main oilield concessions for the irst time, along-

side historic allies such as Exxon Mobil, Total, and

BP. On the downstream side of the energy busi-

ness, it wants to eke out more dollars per barrel

of crude by turning its oil into reined fuels and

products such as plastics and chemicals.

The company is also looking to make its irst

foreign investments in similar plants abroad

where local demand is growing fastest. To inance

that expansion and entice lenders and investors

to the emirate, Adnoc in 2017 sold bonds for the

irst time as well as a sliver of equity—a 10 percent

stake—in its gas station unit.

All of this invites the inevitable compari-

son with Aramco. Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince

Mohammed bin Salman is determined, like Abu

Dhabi’s Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed, to maxi-

mize his country’s oil-related income and use pro-

ceeds from asset sales to build new industries and

help workers develop more sophisticated skills.

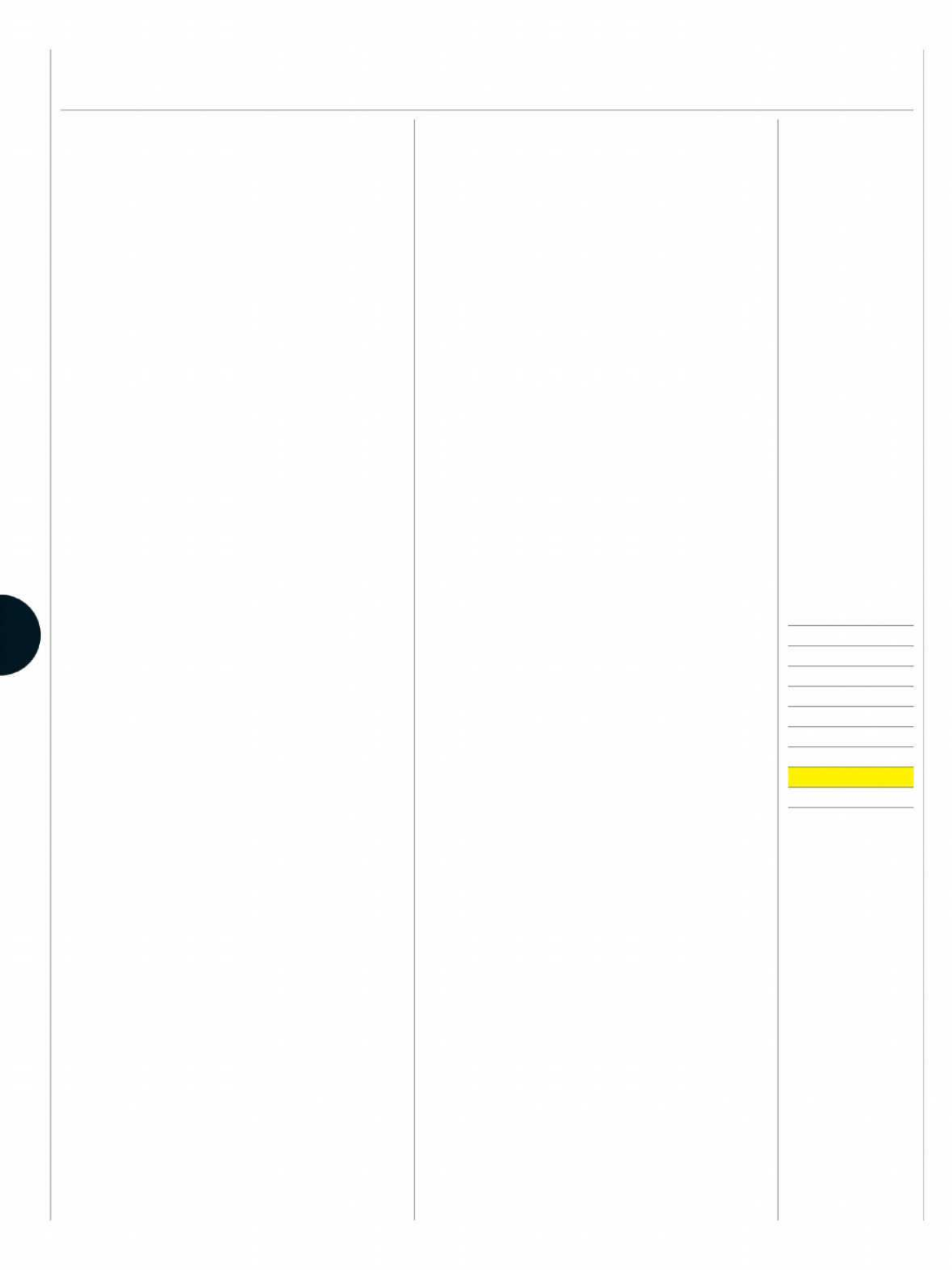

○ Unextracted oil

reserves as of Dec. 31,

2016, in barrels

Venezuela

Saudi Arabia

Canada

Iran

Iraq

Russia

Kuwait

U.A.E.

Libya

U.S.

301

266

172

158

153

110

102

98

48

48

b