82

The Economist

September 22nd 2018

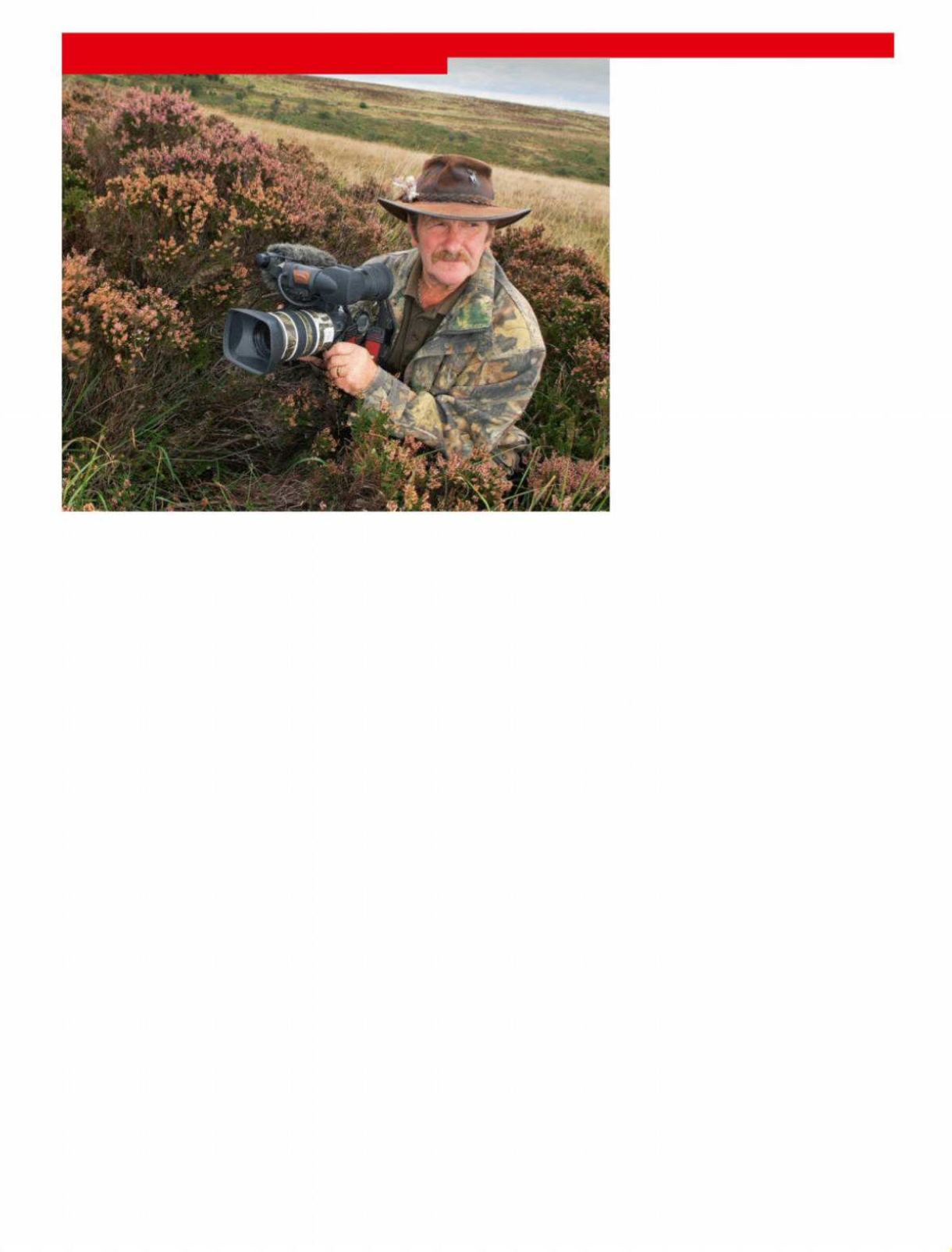

T

HE hints were all around Johnny King-

dom, if he gave it thought. Whenever

he dug a grave, there was always a robin

about. When he took a break, laying down

his spade, pick and shovel, he liked to

watch the ivy-clad churchyard walls

where the blackbirds nested and where

snails tookshelter in the heat of the day. He

even got grudgingly fond of the old cock

pheasant who kept jumping in his graves

and, if he hid behind the headstones,

would perch on the edge as if to say,

“Where’re you to then?”

Truth to say he was watching wildlife

long before a friend put an 8mm video-

camera into his hand and encouraged him

to use it, after a tree-felling accident in 1971

that nearly did for him and left his mind in

pieces for some time. His home-made na-

ture films brought him fame all over the

country and led to several series on

TV

, as

well as books, but he remained theman he

always had been, whose chief enjoyment

(once he was past the girl-chasing-motor-

bike-crashing-cider-soaking years) was to

stay in one place, andwatch.

His place was Exmoor, a land of rolling

heather hills and steep coombes in north

Devon. The sweetest place on Earth. The

water was like gin there; in spring the

woods were white with snowdrops, then

yellow with wild daffodils. You wouldn’t

have a prettier scene. Except for National

Service in Hong Kong, he never left it. He

was born, the only boy in a family of five

girls, in High Bray, and moved about 11

miles to live in Bishop’s Nympton, in a

council house. There he starred in the darts

and football teams and was a fixture at the

Bish Mill pub over the hill. If his wife Julie

made him take holidays he spent them

wishing he was home, with a lovely slice

of bread and syrup and themoor outside.

As forwatching, hewas a past master at

that, patiently observing and easing him-

self closer and closer to a creature. From

boyhood he had learned how to creep up

onwildlife, mostly to catch it for the family

table. He knew how to tickle trout, slowly

stroking their cold smooth bellies and

sides before hooking a finger under a gill to

pull them in; he could camouflage himself

under trees, waiting to spear salmon with

his dung pick, or creep to kill a deer. So he

could also lie on his belly for four hours

with freezing feet to film fox cubs, or stoats

playing. Hewould crawl forward, a fair old

crawl at times, making sure he was down-

wind and that nothing, whether his chub-

by cheeks or his lens rim, was shining up to

give himaway. At some point hemight just

cast in (fishing parlance), to see if he could

pick up something. Then he shot, not with

a bullet, hauling the bloodied bodies

home in the van, but by tagging a button to

set the tape going: his favourite red deer,

such beautiful fine beasts, coming out of a

wooded cleave through the mist, or a rare

mistle thrush pitching on rowan berries

right in his front garden.

He kept trying to get closer. When he

was not gravedigging (sometimes strip-

ping off to reveal his tattoos), hewas usual-

ly in green camouflage, with only his cam-

eras, bigger and heavier over the years,

giving him away. Even the feathers in his

hat, buzzard’s and pheasant’s, served a

purpose to lose him in the heather. He

once got three feet away from an adder in

the brambles, which yawned its pink

mouth fit to swallowhim.

SouthMolton on Thursdays

Several hides were built, most of them on

his very own 52-acre woodland patch of

Exmoor. One was made from a fallen-

down pylon, 29 feet high; from this he

filmed badgers running along an assault

course he had built for them or eating Ju-

lie’s badger cake, made of peanuts, Sugar

Puffs and fat. Another hide, with arm-

chairs in it (where he once served cream

tea) was especially for watching nesting

boxes via a computer. Here he broke his re-

cord for birds in a box, 18wrens all piling in.

Yet another hide, made of wooden boxes

yoked on his shoulders with a camouflage

tent on top, wasmeant to float; from this he

filmed 50 dunlin just beside him, out on

the estuary, until the blasted thing sank.

All thismade great

TV

, when his Devon

burr and twinkling smile were added to

the scenery and the animals. If he could

have filmed the legendary Beast of Ex-

moor, which Julie had seen and he had cer-

tainly heard, it would have been even bet-

ter. But it seemed a funny sort of fame.

Everything startedverysuddenly,whenhe

appeared in a programme called “The Se-

cret of Happiness” in 1993, and his home-

made

DVD

s flew out in hundreds from his

front room; and then it passed over until

the next spurt, in 2006-15. In the interval he

went onwith life as usual, selling his

DVD

s

at local markets (especially at South Mol-

ton on Thursdays), showing them in vil-

lage halls, and digging graves.

He had other jobs, including setting ex-

plosive charges in quarries and helping on

farms, but gravedigging was something

both his father and grandfather had done.

As a small boy he went along to light their

night work with a tilley lamp, shivering at

ghost stories and terrified by the skull his

father thrust up once on his fork. It got to

him sometimes; he had buried friends,

and his parents. But he learned to look

death square in the eye. Under the church

tower at Bishop’sNympton in 2006, where

the ground was always hard, he had dug a

last grave, his own, filling inwith soft earth

tomake a nice easy job.

7

Creeping closer

JohnnyKingdom, gravedigger, poacher andwildlife photographer, died on

September 6th, aged 79

Obituary

Johnny Kingdom