16

REMARKS

Bloomberg Businessweek

October 8, 2018

of the Treasury, warned in a speech at the Carnegie

Endowment for International Peace that “overuse of sanc-

tions could undermine our leadership position within the

global econom

y and the efectiveness of our sanctions them-

selves.” Broad support is best, he said. He added that the U.S.

“must be prepared to ofer sanctions relief if we want coun-

tries to change their behavior.” Trump’s reinstitution of sanc-

tions against the wishes of the coalition partners, without

clear evidence that Iran has meaningfully broken its com-

mitments, appears to violate both of Lew’s principles. (A

spokeswoman said Lew wasn’t available for comment.) Even

Mark Dubowitz, chief executiv

e oicer of the Foundation for

Defense of Democracies, which favors action against Iran,

says that “there’s always risk of overuse of a single instru-

ment. ... You need covert action, military, a regional strategy,

political and information warfare.”

The best thing the dollar has going for it is that its chal-

lengers are weak. The euro represents a monetary union, but

there’s no central taxing and spending authority. Italy’s recent

woes are only the latest challenge to the euro zone’s durability.

China is another pretender to the throne. But China’s undem-

ocratic leadership is wary of the openness to global trade and

capital lows that having a widely used currency requires. In a

December interview with

Quartz

news site, Eichengreen said,

“Every true global currency in the history of the world has

been the currency of a democracy or a political republic, as

far back as the republican city-states of Venice, Florence, and

Genoa in the 14th and 15th centuries.”

On the other hand, the U.S. is hardly alluring these days.

“When does the rest of the world turn to the U.S. and say,

‘What have you done for me lately?’ ” Beth Ann Bovino, chief

U.S. economist of S&P Global Ratings, asked on Sept. 30 at

the annual meeting of the National Association for Business

Economics in Boston.

The biggest long-term challenge to the dollar’s standing is

what economists term the Triin dilemma. Belgian-American

economist Robert Triin observed in 1959 that for the U.S.

to supply dollars to the rest of the world, it must run trade

deicits. Trading partners stash the dollars they earn from

exports in their reserve accounts instead of spending them on

American goods and services. Eventually, though, the chronic

U.S. trade deicits undermine conidence in the dollar. This

is what forced President Richard Nixon to abandon the dol-

lar’s convertibility to gold in 1971.

Harvard economist Carmen Reinhart cited the dollar’s

Triin dilemma at the Boston business economists’ meet-

ing. “Now you say, well, that’s not a problem, our debt is not

backed by gold,” she said. “But our debt, and anybody’s debt,

is ultimately backed by the goods and services that an econ-

omy produces.” And, she noted, “our share of world [gross

domestic product] is shrinking.”

When Giscard d’Estaing coined the phrase “exorbitant

privilege,” he was referring to the fact that the U.S. gets what

amounts to a permanent, interest-free loan from the rest of the

world when dollars are held outside the U.S. As Eichengreen

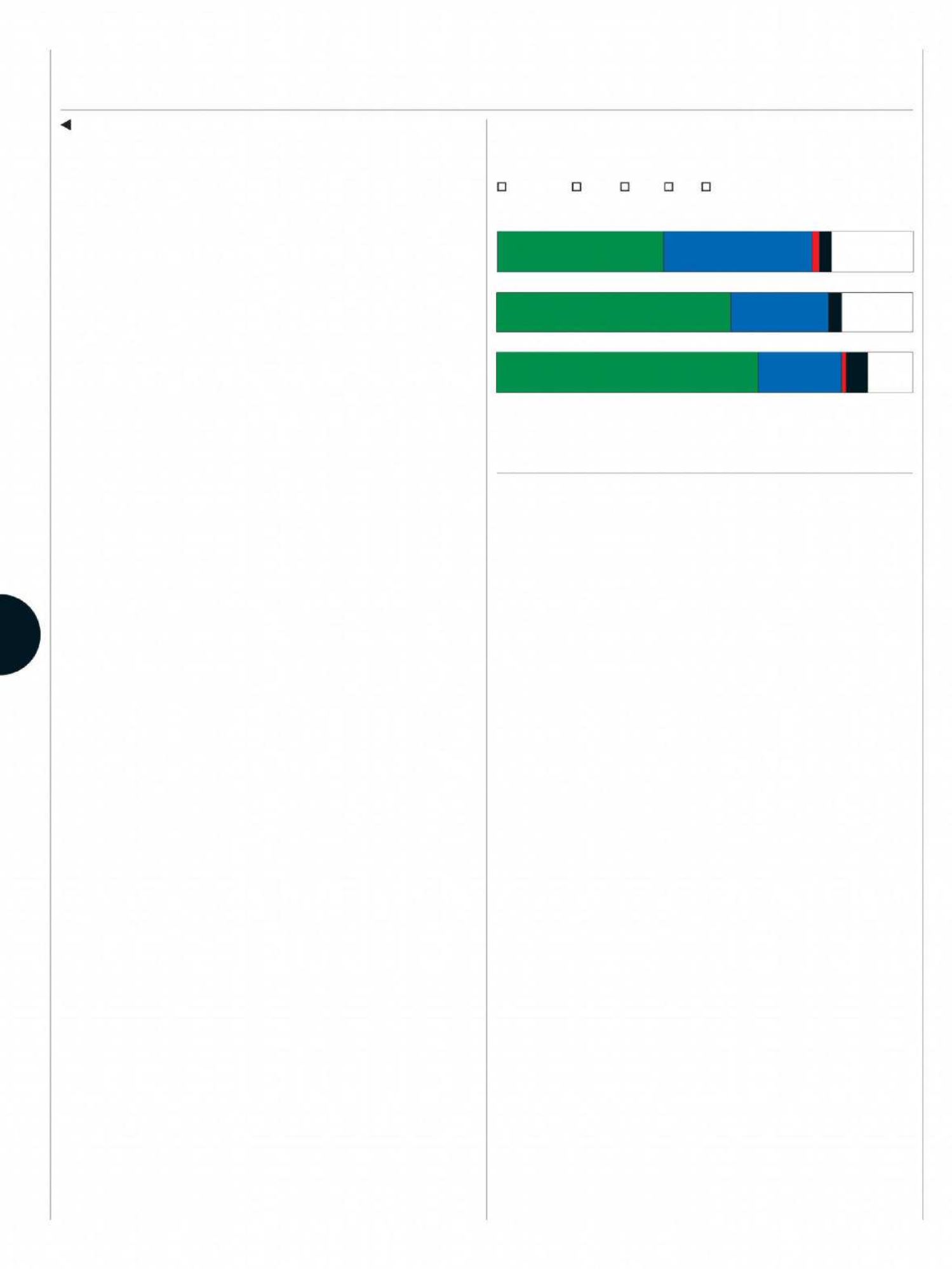

U.S. dollars Euros Yuan Yen Other

Global payment currency

International loans

Foreign exchange reserves

DATA: BANK FOR INTERNATIONAL SETTLEMENTS, INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND, SOCIETY FOR WORLDWIDE

INTERBANK FINANCIAL TELECOMMUNICATION, AND EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK CALCULATIONS

Each currency’s share of the category in the international monetary system as of

the 2017 fourth quarter or latest available

40%

56%

63%

36%

23%

20%

20%

17%

11%

How Much Is That in Dollars?

points out, it costs only a few cents for the U.S. Bureau of

Engraving and Printing to produce a $100 bill, but other coun-

tries have to pony up $100 worth of actual goods and ser-

vices to obtain one. Dollars that foreigners willingly accept

and trade among themselves are like little green IOUs to the

rest of the world. They allow Americans collectively to con-

sume more than they produce—to live beyond their means.

The downside to America’s privilege is that the for-

eign demand for dollars raises the exchange rate, mak-

ing American products less competitive in world markets.

Especially in slack times, American workers can be thrown

out of work when the U.S. imports products that could have

been made domestically. And the accumulation of dollars out-

side the U.S. represents a transfer of wealth to other coun-

tries. If other countries suddenly decide to use their dollars

to buy American goods and services, the U.S. will suddenly

have plenty of work to do—but consumers will have to switch

from living beyond their means to living beneath their means.

On the whole, though, U.S. leadership beneits from hav-

ing a currency that’s in great demand. The issue is how to

keep the dollar the favored currency of the world. Preserving

diplomatic alliances is one way. Eichengreen’s research inds

that countries that rely on the U.S. nuclear umbrella ( Japan,

Germany) have a much bigger share of dollars in their for-

eign exchange reserves than countries that have their own

nukes, such as France, apparently because they feel their

dollar dependence tightens their military protector’s ties

to them. Another way is to make dollars freely available as

needed to trading partners, as the Federal Reserve did via

“swap lines” during the global inancial crisis under Chairman

Ben Bernanke. And yet another is to refrain from using the

dollar’s dominance as a cudgel against allies. As Lew said in

2016, “the more we condition use of the dollar and our inan-

cial system on adherence to U.S. foreign policy, the more

the risk of migration to other currencies and other inancial

systems in the medium term grows.” —

With Nick Wadhams,

Gregory Viscusi, and Jeanna Smialek