The Economist

June 9th 2018

Books and arts 73

1

2

There is a female assassinwho goes by the

codename Bach.

For much of the ride, it is not clear quite

what Mr Clinton has contributed. But, just

as more than 500 pages tick towards zero,

the presidential co-author finally gets his

hands on the plot. Having seen offthe bad-

dies and saved America and theworld, the

hero tries a spot of bipartisan rallying.

In an address to a joint session of Con-

gress, he reveals why he had to abscond

from the White House—while also calling

for immigration reform, gun controls, a

meaningful climate-change debate and a

return to the FoundingFathers’ ambition to

form a more perfect union. “After the

speech, my approval ratings rose from less

than 30% to more than 80%. I knew it

wouldn’t last, but it felt good to be out of

the dungeon.” In his dreams.

7

T

HE Hanford nuclear complex in Wash-

ington state contained radioactive alli-

gator carcasses. Nuns used their blood to

daub crosses on a missile silo in Colorado.

In Cumbria, northern England, 1,500 con-

taminated birds were killed and buried

with some radioactive garden gnomes.

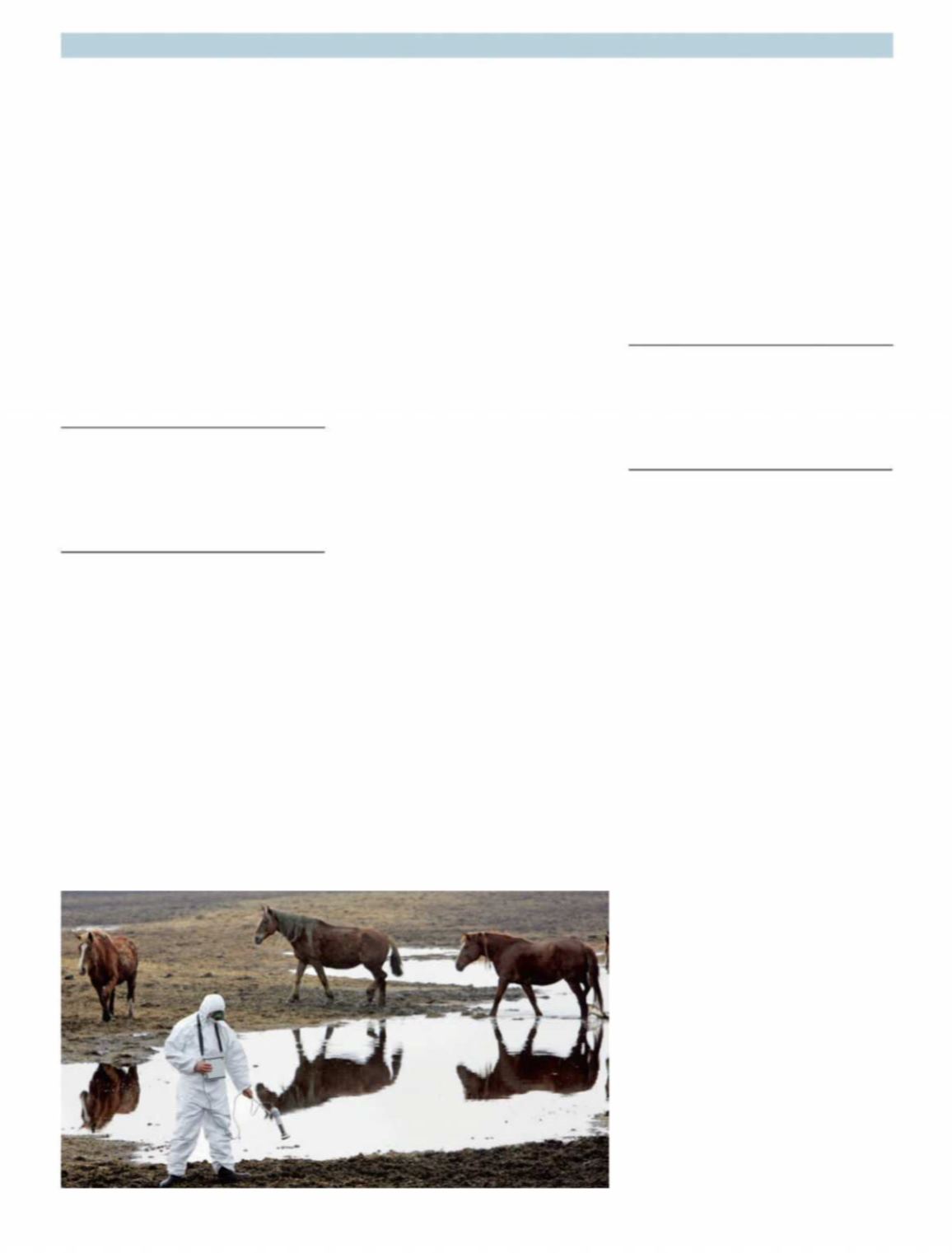

These lurid tales from the nuclear

worldare all real. But the industryalso gen-

erates myths that are widely accepted as

true. For example, Chernobyl is not a dead

zone: its wildlife thrives (see picture), and

many returnees have lived into ruddy old

age, eating produce from the radioactive

soil. The evidence suggests those who die

early are the evacuees who, Fred Pearce

writes, “languish unhappily in distant

towns—free of radiation but often con-

sumed by angst, junk food and fear.” Like-

wise, no one seems to have died as a direct

result of the meltdown at Fukushima. The

deaths related to the accident were mainly

suicides prompted by the chaotic evacua-

tion and loss of home, jobs and family.

“Psychological fallout” can be lethal.

When the truth seems ludicrous, and

falsehoods are widely believed, facts can

be elusive. In “Fallout”Mr Pearce, a veteran

science journalist, travels the world to pin

down what he calls “the radioactive lega-

cies of the nuclear age”. He moves be-

tween weaponry and energy, cataloguing

mistakes, dishonesty and irrational fears.

The result is a panorama of atomic grotes-

querie that is at once troubling, surprising

and ruthlessly entertaining.

His nuclear odyssey yields some hid-

eous examples of the industry’s secrecy,

particularly a visit to the Russian village of

Metlino, on the Techa river in the Urals. In

the 1950s this was the world’s most radio-

active river; Mr Pearce reckons it may have

been responsible for more sickness than

all of the other nuclear incidents in history

combined. Upstream sat the Mayakpower

plant, which “poured into it an average of

one Olympic swimming pool’s worth of

highly radioactive liquids every two

hours.” Villagers received “staggering”

doses of radiation; scientists quietly moni-

tored the rates of illness and death.

Such callous episodes, and better-

known calamities such as Chernobyl and

Fukushima, dominate the nuclear debate.

As Mr Pearce observes, similar attention is

rarely given to various studies demonstrat-

ing that no link exists between nuclear

plants and local cancer rates, nor the pains-

taking schemes, such as those in Germany,

to safely dispose of nuclear waste. His

deepest worry is about Britain’s Sellafield

plant, home to a massive stockpile of plu-

tonium. In 1995 its fence was easily scaled

by Greenpeace activists, who sprayed

“bollocks” on the walls. A bomb sent

across the fence could result in “a terrorist

Chernobyl”, yet Mr Pearce saw little being

done to reinforce the site.

He asks how long the beleaguered nuc-

lear-power industry can survive—hobbled

as it is by the association with nuclear

weapons (“the Achilles’ heel of civil nuc-

lear power”), a litany of disasters and the

doomsdayhyperboleofanti-nuclearactiv-

ists. Mr Pearce recognises that “most civil-

ian nuclear activities are safe”, but notes

that in democracies, at least, the public has

the power of veto, however sensibly they

wield it.

7

The nuclear industry

The writing on the

wall

Fallout: Disasters, Lies and the Legacy of

the Nuclear Age.

By Fred Pearce.

Beacon

Press; 264 pages; $27.95. Portobello Books;

£14.99

Life inside the zone

T

HE tale of the “Lost Colony” is a 400-

year chronicle of madness and delu-

sion. As Andrew Lawler recounts in “The

Secret Token”, it begins in 1587 with the ill-

conceived, ill-executed attempt to found

the New World’s first English settlement

on Roanoke Island, and continues to this

day in the obsessive quest to discover how

and why the colony disappeared. Both the

original settlers and those who, over the

subsequent centuries, have quixotically

tried to trace them seem equally deluded.

They are all mirage-chasers, confident (de-

spite ample evidence to the contrary) that

the ultimate prize iswithin their grasp.

In the case of the colonists, that prize

was mountains of diamonds or gold, or a

quick passage to Asia. For historians, ar-

chaeologists and amateur sleuths, it is the

equally elusive object or text that will re-

veal the Lost Colony’s fate. Yet in truth

there is nothing verymysterious about the

failure of the Roanoke settlement.

Thisbid to establisha Europeanoutpost

offwhat is nowthe coast ofNorthCarolina

was doomed by ignorance of the basic

facts of geography, geology and geopoli-

tics. Conceived by Sir Walter Raleigh, a fa-

voured courtier of Elizabeth I, as a means

to “wrest the keys of the world from

Spain”, the site was chosen “because on

the mainland there is much gold”—and be-

cause Raleigh assumed it was strategically

placed near an easy passage between the

Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

None of these assumptions was

grounded in reality. And reality quickly

struck back, in the form of disease, starva-

tion, hostile natives and even more hostile

Spaniards. Hoping to obtain desperately

needed supplies, John White, the gover-

The Lost Colony

Myth and

madness

The Secret Token: Myth, Obsession and the

Search for the Lost Colony of Roanoke.

By

Andrew Lawler.

Doubleday; 426 pages; $29.95