72 Books and arts

The Economist

June 9th 2018

1

2

Russian Linesman.”

Fittingly, the linesman to whom that

name referred was not actually Russian.

His name was Tofiq Bahramov and he was

from Azerbaijan. Bahramov officiated at

the World Cup final of 1966, played be-

tween England and West Germany at

Wembley Stadium in London. With the

scores level in extra time, a shot by Geoff

Hurst, England’s striker, rattled the cross-

bar and bounced down over the goal line.

Or perhaps it didn’t: the German players

claimed to have seen chalkdust, indicating

that the ball hit the line and thus that the

goal should not be given. The referee

jogged across to consult Bahramov, who

briskly nodded an affirmative.

England won 4-2. English fans mostly

remember the fourth goal, scored in the fi-

nal seconds as the joyous crowd spilled

onto the pitch. But it is the third that is a

work of art. Just as Hamlet’s psychology

and the Mona Lisa’s smile become more

enigmatic with each viewing, however

many times you watch Mr Hurst’s shot,

you can never knowfor sure.

4. The tragic hero.

TheWorld Cup final

in Berlin in 2006 was the last game Zine-

dine Zidane ever played. He had already

won the tournament once, spurringFrance

to victory in 1998. After that, he was more

than a footballer. In a country where Jean-

Marie Le Pen of the National Front made it

to the run-off in the next presidential elec-

tion, Mr Zidane—the son of an Algerian

warehouseman—became the face of a

more tolerant France. Crowds in Paris

chanted for him to be president.

The match in Berlin was heading for a

penalty shoot-out; Mr Zidane, France’s

captain, had already scored one in the

game.With tenminutes to go, an Italiande-

fender muttered something to him (about

his mother, Mr Zidane alleged; only about

his sister, the defender maintained). Mr Zi-

dane headbutted the Italian in the chest.

Hewas sent off. France lost the shoot-out.

This implosionwas a tragedy in the pur-

est sense. A tragedy, wrote Aristotle in the

fourth century

BC

, depicts the fall of a great

but flawedman, andhinges ona

peripeteia

,

or sudden reversal, like the Italian defend-

er’s slur. For Bernard-Henri Lévy, a French

intellectual, themeltdown represented the

“suicide of a demigod”—a tragic hero of

whom too much has been demanded.

Watch the scene closely, and there is in-

deed something oddly composed inMr Zi-

dane’s demeanour as, jogging away from

his opponent, he hears, stops, and turns

back tomeet his fate.

5. A crack in everything

.

According to

the Japanese aesthetic known as

wabi-

sabi,

beauty is not perfect but flawed and

incomplete. Leonard Cohen expressed the

same thought in “Anthem”: “Forget your

perfect offering/There is a crack in every-

thing/That’showthe light gets in.” So, inad-

vertently, did Pelé, after he won the race

with the Uruguayan goalkeeper.

Perhaps no one but Pelé would have

donewhat he did next. He did nothing. His

mind whirring faster than his feet, he did

not touch the ball, as the keeper expected,

but let it run on—hastily collecting it, after

his

coup de théâtre

, on the other side of his

opponent. Pelé shot towards the unguard-

ed goal—but scuffed his kickandmissed.

He still avenged his father and the

Ma-

racanazo

. Brazil beat Uruguay andwon the

final, inwhich Pelé scored. Still, much later

he said he had dreams in which, after that

audacious moment of restraint, his aim

was true: “It would have been so much

more beautiful had it gone in.” He may be

the greatest football artist of all time, but,

about this, Pelé is wrong. The kink in the

masterpiece iswhat makes it human.

7

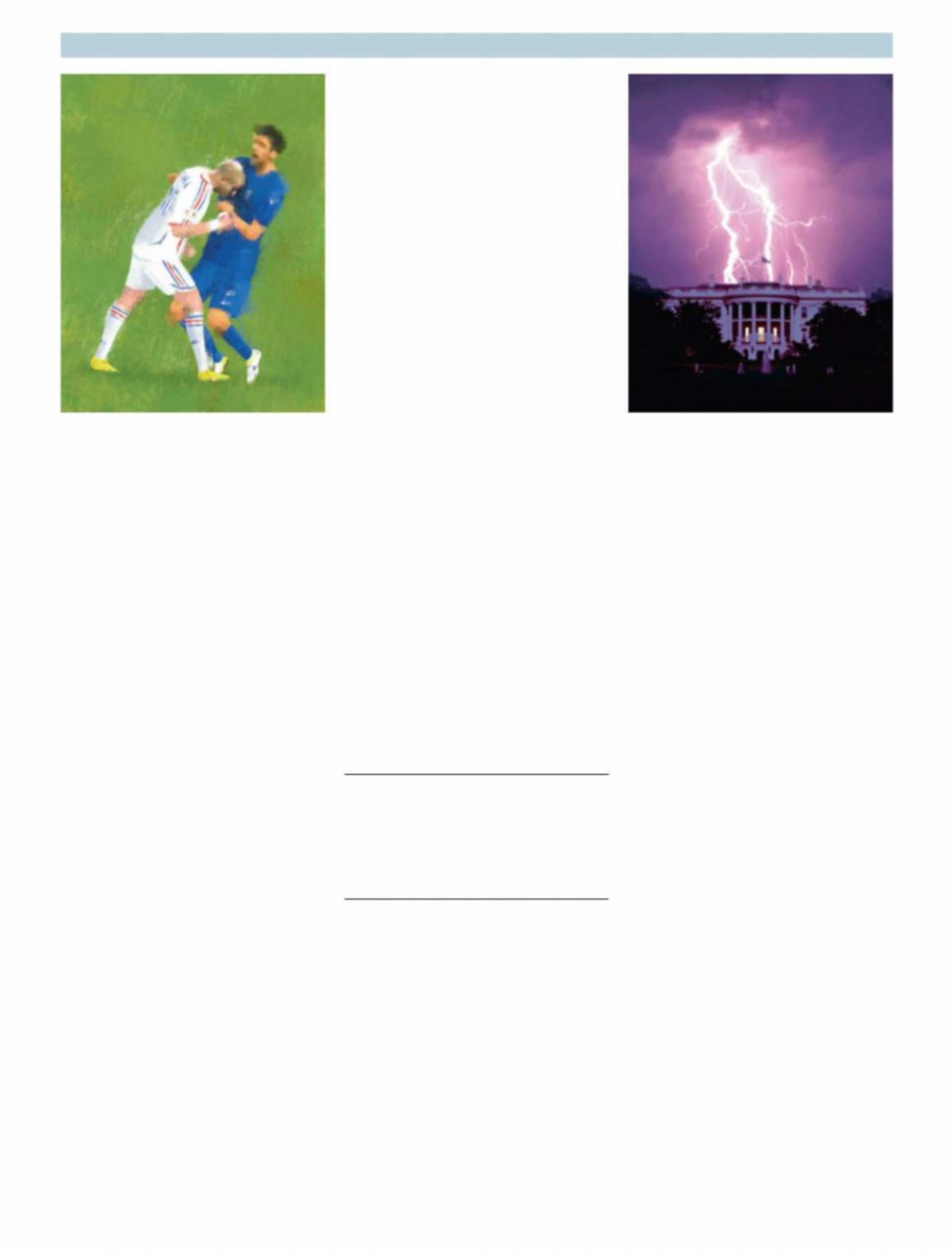

O

NE of themwas a publishingmachine

with scores of bestsellers under his

belt. The other knew the White House like

the back of his hand (because he lived in it

for eight years). Together they made a per-

fect thriller-writing team. Or so claims the

marketing for Bill Clinton’s debut novel,

“The President isMissing”, co-writtenwith

James Patterson, whose books have sold

over 375m copies. Insider knowledge!

Thrills and spills! More of the latter than

the former, it turns out.

Inwhat seems a case ofwish-fulfilment

in more ways than one, “The President is

Missing” features a morally unimpeach-

able president—a former soldier who was

captured and tortured by the enemy but

never said a word (his middle name is Lin-

coln rather than Jefferson). Now he is

stressed, sick and grieving, juggling bitter

enemies and uncertain friends. Suddenly

he faces a crisis of such magnitude that it

involves saving not only America from ca-

tastrophe, but probably the entire human

race. “Not since Kennedy stared down

Khrushchev over the missiles in Cuba has

our nation been this close to world war,”

the president muses. To stand any chance

of success, he must go spectacularly off-

piste. Hence the title.

Alas, “The President is Missing” is itself

missing some things that might have im-

proved it. It is short of real political insight,

which is surprising. There is no sex, which

may or may not be even more surprising.

What it offers instead are 128 chapters of

breathless, onward-rushing, monosyllabic

prose and enough twisty plotting to give

the reader a bad case of whiplash (mixed

metaphors intentional). The storyline

swings back and forth between the presi-

dent and his pals—an imposing chancellor

of Germany called Juergen Richter who

looks “like something out of British royal-

ty”, a Russian prime minister with an iron

handshake and a gushy Israeli premier.

“Youknowthat Israelwill never leave your

side,” she assures the president.

The assembled global uppy-ups and

dirty low-lifers spend the book hopping

across highways and down cul-de-sacs.

The plot is epic and unlikely, and includes

such grand concerns as terrorism, comput-

er shutdowns, the threat of chaos, civil dis-

order, and death on a gigantic scale. As a

helpful timer ticks down the minutes, the

denouement comes with just three sec-

onds to spare. There are baddies who turn

out to be goodies, and a goody who turns

out to be very bad indeed: an ambitious

woman with a soul shrivelled by envy.

Presidential fiction

Good guywith a

gun

The President is Missing.

By Bill Clinton

and James Patterson.

Little, Brown

and

Knopf; 528 pages; $30. Century; £20

Trouble at t’mill