vineyard,” he says. “How do I come in here, tear it all out,

and replant it? It’ll be three years until any production comes

back.” Pre-lanternly, he harvested 3 tons per acre of vineyard

and sold the grapes for $2,000 a ton, grossing $240,000 a year.

Were he to stop producing entirely for those three years, he’d

lose that annual income, to say nothing of the risk that lantern-

lies will infest newly planted vines. Even the grapes that sur-

vive are an oenophile’s nightmare—one winemaker Beekman

supplies told him that batches produced from bug-ridden

Riesling and Traminette grapes are redolent of cabbage.

For the forestry industry, the economic hardships have

thus far been less direct. So far the destruction has been

limited, but the trees’ capacity as carriers has been hurting

companies just the same. “Logs have to get inspected pretty

heavily,” says Don Kellenberger, the owner of a small log-

ging and land-clearing company in Berks County. “We have

to spend more time, and there’s no extra money to do that.

So it’s costing us more, and we’re getting paid the same.”

Some tracts of land in the quarantine zone are so infested

that companies won’t even harvest tree species that lantern-

lies generally ignore, lest they transport the insects into a

new community or into their own sawmills.

“This particular pest is such an excellent hitchhiker,” says

Hall-Bagdonas, of the Northern Tier Hardwood Association.

“It lays its eggs on anything lat. It’s adapting and doing dif-

ferent things every year.” Adult lanternlies, once thought to

be better hoppers than lyers, have recently been observed

winging between trees, for instance. “They were lying into

headwinds and lying further distances than we thought they

could,” Penn State’s Swackhamer says.

Long-distance travel is oicials’ biggest fear. Biddinger sus-

pects it’s only a matter of time until the 15,000 acres of juice

grapes along the south shore of Lake Erie in northwestern

Pennsylvania are hit. Once lanternlies inish feeding there,

they might move to the 30,000 acres of juice grapes across

the border in New York. Maryland and Delaware haven’t been

infested yet, but entomologists consider that more luck than

anything else. The bugs have already hopped past Maryland

to get to Virginia, where egg masses have been spotted by the

hundreds; researchers’ best guess is that a mass hitchhiked

some 180 miles to get there. Even Michigan, with a combined

80,000 acres of blueberry and cherry crops, is eyeing the

spread warily, Biddinger says.

The worst-case economic scenario for Pennsylvania, and

the rest of the country, would be for the spotted lanternly

to overrun the Port of Philadelphia. The lat shipping con-

tainers there would make excellent larval grounds, which,

combined with heavy shipping and trucking traic, could

help the bugs spread quickly to the south and west. Beekman

points out, too, that the port isn’t far from 30th Street Station,

Philly’s main passenger rail depot, visible from the hills of

his vineyard. Ominously, in August parks oicials found

lanternlies in four urban locations, including Center City

and the Horticulture Center at West Fairmount Park, a pop-

ular wedding venue close to the city’s art museum.

“The bugs aren’t good. They’re moving,” says Beekman.

“You’re going to see the spread of this is farther than any-

one projected.”

n a sweltering afternoon, Rick Hartlieb, a 10-year

veteran of the Pennsylvania Bureau of Forestry,

drives his pickup truck to a clearing on Gibraltar

Hill, an area of William Penn State Forest about

35 minutes south of Beekman’s grapevines. We

park, exit, and walk over to a lone ailanthus cov-

ered with pockets of lanternlies: a few dozen

ndful there, maybe 200 from trunk to canopy.

Standing beside the tree, I feel a distinct misting sensation,

then notice small droplets on my forearms. “That’s the honey-

dew,” Hartlieb says. I’m being barfed on by bugs.

I soon see that some of the lanternlies aren’t moving.

They’ve been killed, Hartlieb explains, by a chemical called

dinotefuran. The insecticide is classiied as a systemic, which

means it’s sprayed onto trees and absorbed into the plant,

ready to be sucked out by unwitting lanternlies. Hartlieb and

his colleagues have sprayed about 50 trees in this area, part

of a pilot project funded by the state and designed to pro-

duce a measurable lanternly reduction before next spring,

when a new generation spawns. Biddinger is running a sim-

ilar trial on a plot of farmland adjacent to Penn State’s Berks

County campus, spraying potted peach trees and grapevines

with various insecticides, including dinotefuran.

Systemics proved efective in killing the stink bug when it

made its way to Pennsylvania, but the chemicals are costly,

and combating an entire species requires a lot of spraying.

For the forestry industry, the hope is that a single treatment

of a spray such as dinotefuran will last a year; determining

the chemical’s persistence is one aim of Hartlieb’s pilot. “The

important thing is we’re trying. Hopefully doing something

is better than doing nothing,” he says.

68

Bloomberg Businessweek

October 8, 2018

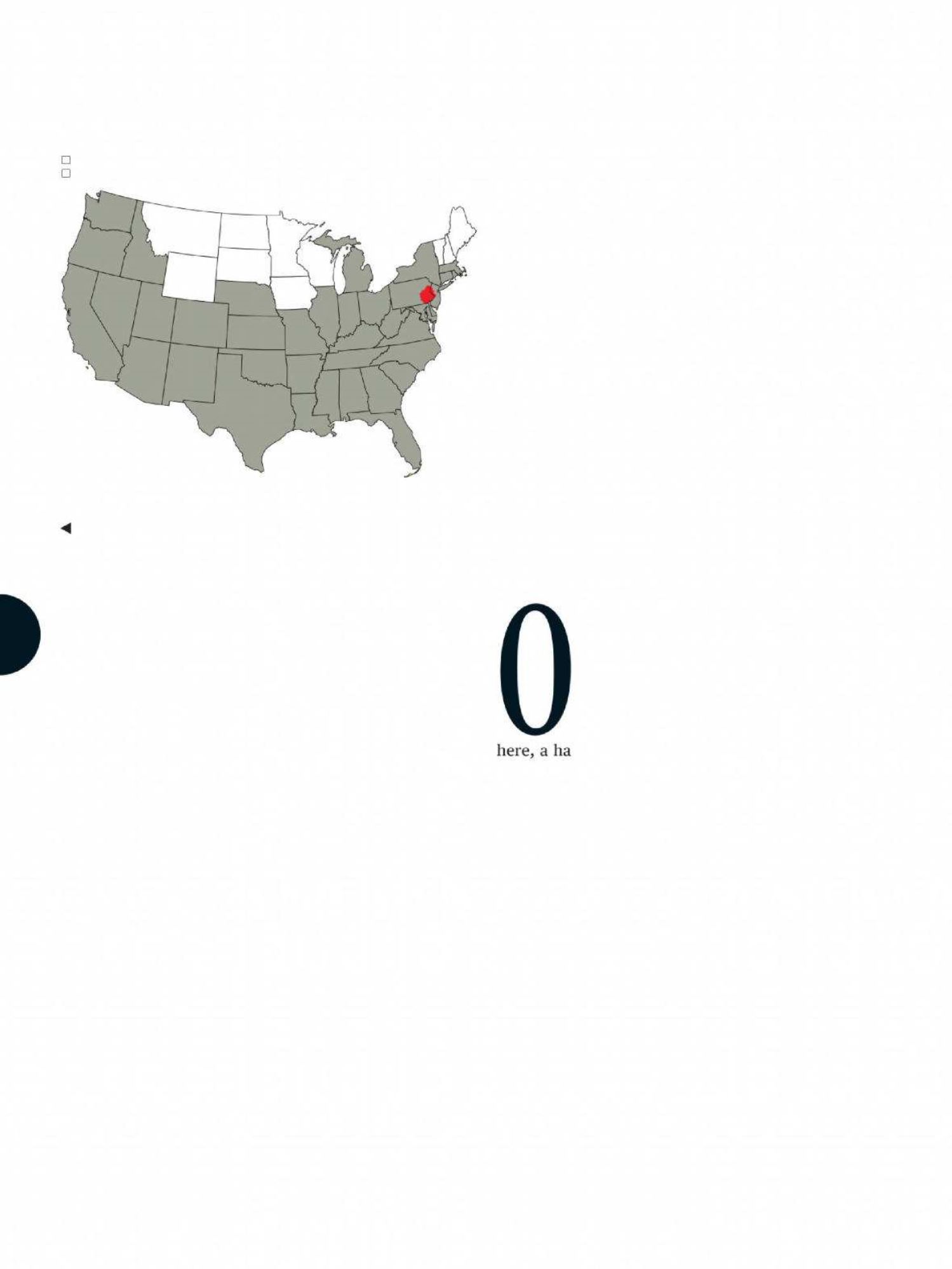

States with habitat suitable for the spotted lanternfly

Counties under quarantine

DATA: USDA; NEW JERSEY DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE; PENNSYLVANIA DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE

COMING SOON TO A FOREST NEAR YOU?