66

Bloomberg Businessweek

May 14, 2018

teams and getting his way. He never lost his temper, but his

mind, once set, was like granite. Benter was also unwilling to

budge. Their alliance was over. In a it of pique, Benter wrote

a line of code into the software that would stop it from func-

tioning after a given date—a digital time bomb—even though

he knew it would be trivial for Woods to ind and ix it later.

Woods would keep betting algorithmically on horses, Benter

was sure of that. He resolved that he would, too.

enter’s Las Vegas friends wouldn’t stake him at

horse racing, but they would at blackjack. He

took their money to Atlantic City and spent two

years managing a team of card counters, brood-

ing, and working on the racing model in his spare

time. In September 1988, having amassed a few hundred thou-

sand dollars, he returned to Hong Kong. Sure enough, Woods

was still there. The Australian had hired programmers and

mathematicians to develop Benter’s code and was making

money. He’d moved into a penthouse lat with a spectacular

view. Benter refused to speak to him.

Benter’s model required his undivided attention. It moni-

tored only about 20 inputs—just a fraction of the ininite fac-

tors that inluence a horse’s performance, from wind speed

to what it ate for breakfast. In pursuit of mathematical per-

fection, he became convinced that horses raced diferently

according to temperature, and when he learned that British

meteorologists kept an archive of Hong Kong weather data

in southwest England, he traveled there by plane and rail.

A bemused archivist led him to a dusty library basement,

where Benter copied years of igures into his notebook.

When he got back to Hong Kong, he entered the data into

his computers—and found it had no efect whatsoever on

race outcomes. Such was the scientiic process.

Other additions, such as the number of rest days since a

horse’s last race, were more successful, and in his irst year

after returning to Hong Kong, Benter won (as he recalls)

$600,000. The next racing season, ending in the summer

of 1990, he lost a little but was still up overall. He hired an

employee, Coladonato, who would stay with him for years,

and a rotating cast of consultants: independent gamblers,

journalists, analysts, coders, mathematicians. When the vol-

ume of bets rose, he recruited English-speaking Filipinos from

the ranks of the city’s housekeepers to relay his bets to the

Jockey Club’s Telebet phone lines, reading wagers at the rate

of eight a minute.

A breakthrough came when Benter hit on the idea of incor-

porating a data set hiding in plain sight: the Jockey Club’s

publicly available betting odds. Building his own set of odds

from scratch had been proitable, but he found that using

the public odds as a starting point and reining them with his

proprietary algorithm was dramatically more proitable. He

considered the move his single most important innovation,

and in the 1990-91 season, he said, he won about $3 million.

The following year the Hong Kong Jockey Club phoned

Benter at an oice he’d established in Happy Valley. He

winced, remembering the meaty hand of the Las Vegas pit

boss on his shoulder. But instead of threatening him, a Jockey

Club salesperson said, “You are one of our best customers.

What can we do to help you?” The club wasn’t a casino try-

ing to root out gamblers who regularly beat the house; its

incentive was to maximize betting activity so more revenue

was available for Hong Kong charities and the government.

Benter asked if it was possible to place his bets electronically

instead of over the phone. The Jockey Club agreed to install

what he called the “Big CIT”—a customer input terminal. He

ran a cable from his computers directly into the machine and

increased his betting.

Benter had achieved something without known precedent:

a kind of horse-racing hedge fund, and a quantitative one

at that, using probabilistic modeling to beat the market and

deliver returns to investors. Probably the only other one of

its kind was Woods’s operation, and Benter had written its

code base. Their returns kept growing. Woods made $10 mil-

lion in the 1994-95 season and bought a Rolls-Royce that he

never drove. Benter purchased a stake in a French vineyard.

It was impossible to keep their success secret, and they both

attracted employees and hangers-on, some of whom switched

back and forth between the Benter and Woods teams. One

was Bob Moore, a manic New Zealander whose passions were

cocaine and video analysis. He’d watch footage of past races

to identify horses that should have won but were bumped or

blocked and prevented from doing so. It worked as a kind of

bad-luck adjuster and made the algorithms more efective.

The computer-model crowd spent nights in a neighborhood

called Wan Chai—a honey pot of gaudy bars and topless danc-

ers that’s been described as “a wildly liberated Las Vegas.”

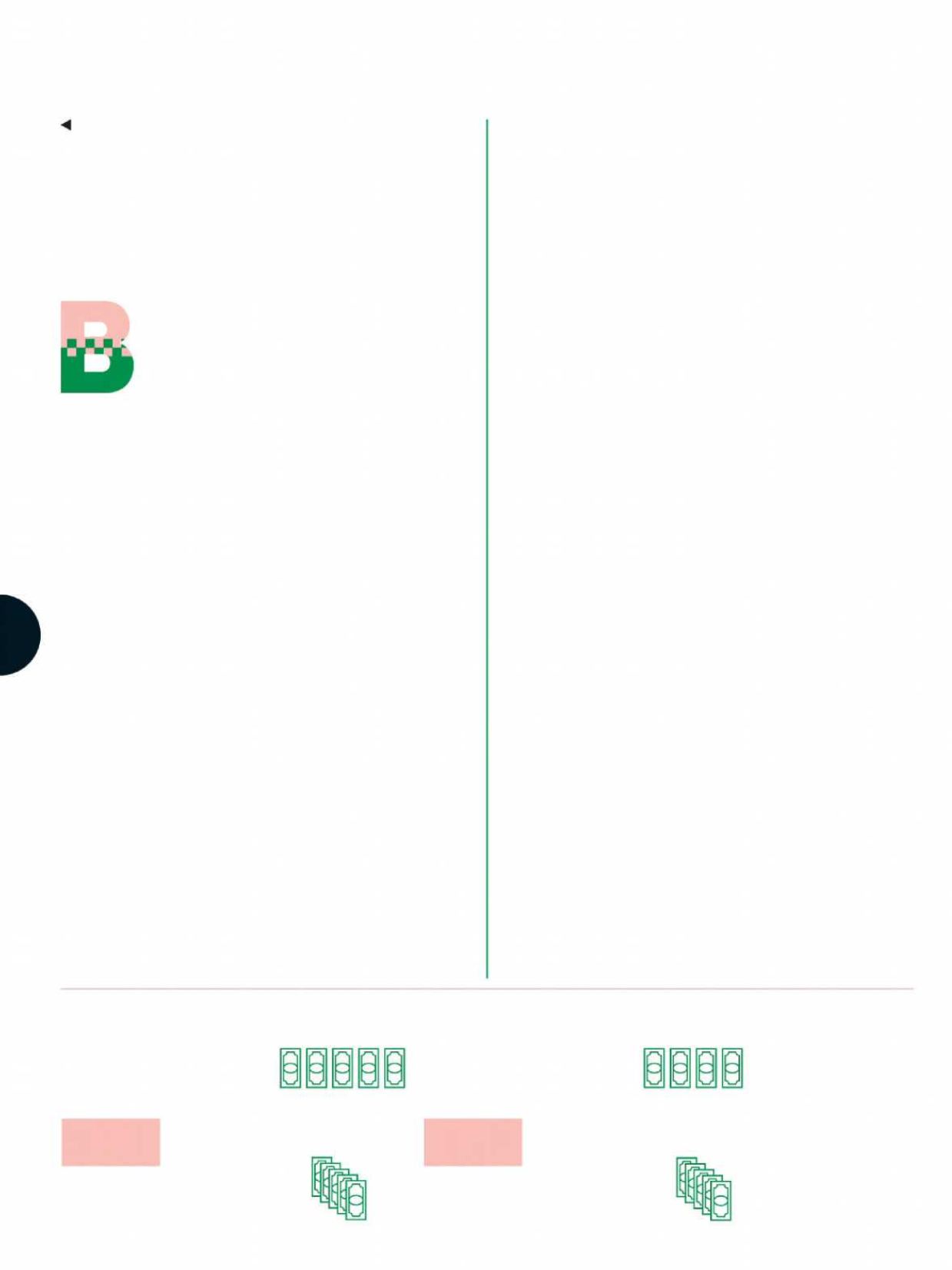

Benter’s Math (Radically Simplified)

Let’s say Seabiscuit is about to

run at Happy Valley Racecourse.

These numbers

suggest that if

the race were

conducted five

times, Seabiscuit would win once for

every four losses.

Benter’s

algorithms—

tracking inputs

like straight-line

speed, recuperation time, weather,

etc.—predict Seabiscuit will

actually win one of every

four

hypothetical races.

Public odds

Benter’s odds

4

to

1

3

to

1

A gambler who bet $1

five times could expect

to win $5—pointless.

That means Benter can

bet $1 four times to

win $5. That’s a profit

margin of 25 percent.

A small edge can

turn into big profit

when multiplied

across thousands

and thousands of

races. Benter says

his gambling systems

have made close to

$1 billion.