The Economist

May 26th 2018

75

For daily analysis and debate on books, arts and

culture, visit

Economist.com/culture1

O

N A stage in a park in Harare, Zimba-

bwe’s capital, Carl Joshua Ncube, per-

haps the country’s most famous comedi-

an, is coaching a novice. Imitating her act,

in which she pretends to deliver a baby, he

mimes a doctor slapping its bottom. “Peo-

ple love to hear about bottoms,” he tells

her. An hour or so later, he introduces her—

and three other wannabe female comics,

one ofwhom is hiswife—to a big audience.

“In Zimbabwe we only have one female

comedian,” he says, mock-solemnly. “We

need some competition for Grace!” Feign-

ing anxiety, he adds: “Although we know

what happens when people try to intro-

duce theirwives to the profession!”

By Grace, Mr Ncube of course means

Mugabe, the couture-loving wife of Robert

Mugabe, Zimbabwe’s leader until his re-

moval last November. Before the coup de

Grace, jokes at her expense were a bit ris-

qué. These days they can be told any-

where, loud and clear. “Operation Restore

Regasi”, a play crudely satirising the Mu-

gabes, sold out repeatedly earlier this year

(the name parodies an army commander

who mispronounced Operation Restore

Legacy, the coup’s code-name). At this

month’s Harare International Festival of

Arts, where Mr Ncube was performing,

Freshlyground, a band with members

from across southern Africa, ended the

jamboree with a song ridiculing Mr Mu-

gabe, to raucous applause.

Satire may be the country’s fastest-

nonetheless, perhaps thanks to the abun-

dance of material. One of the most promi-

nent groups is an organisation called the

Magamba Network. Since 2011 it has pro-

duced a satirical news show called the

“Zambezi News”, mocking the state broad-

caster,

ZBC

, and the stoogeswho appear on

it. Before the coup, the group’s offices were

repeatedly raided. AnAmerican employee

was arrested and charged with attempting

to overthrow the government.

From a purely comic perspective, Mr

Ncube says, the repression had an upside:

“The jokes were better because there was

that fear.” But finding a way to remain fun-

ny is not Zimbabwean comedians’ only

worry. They are also trying to ensure that

their newfound licence is not revoked.

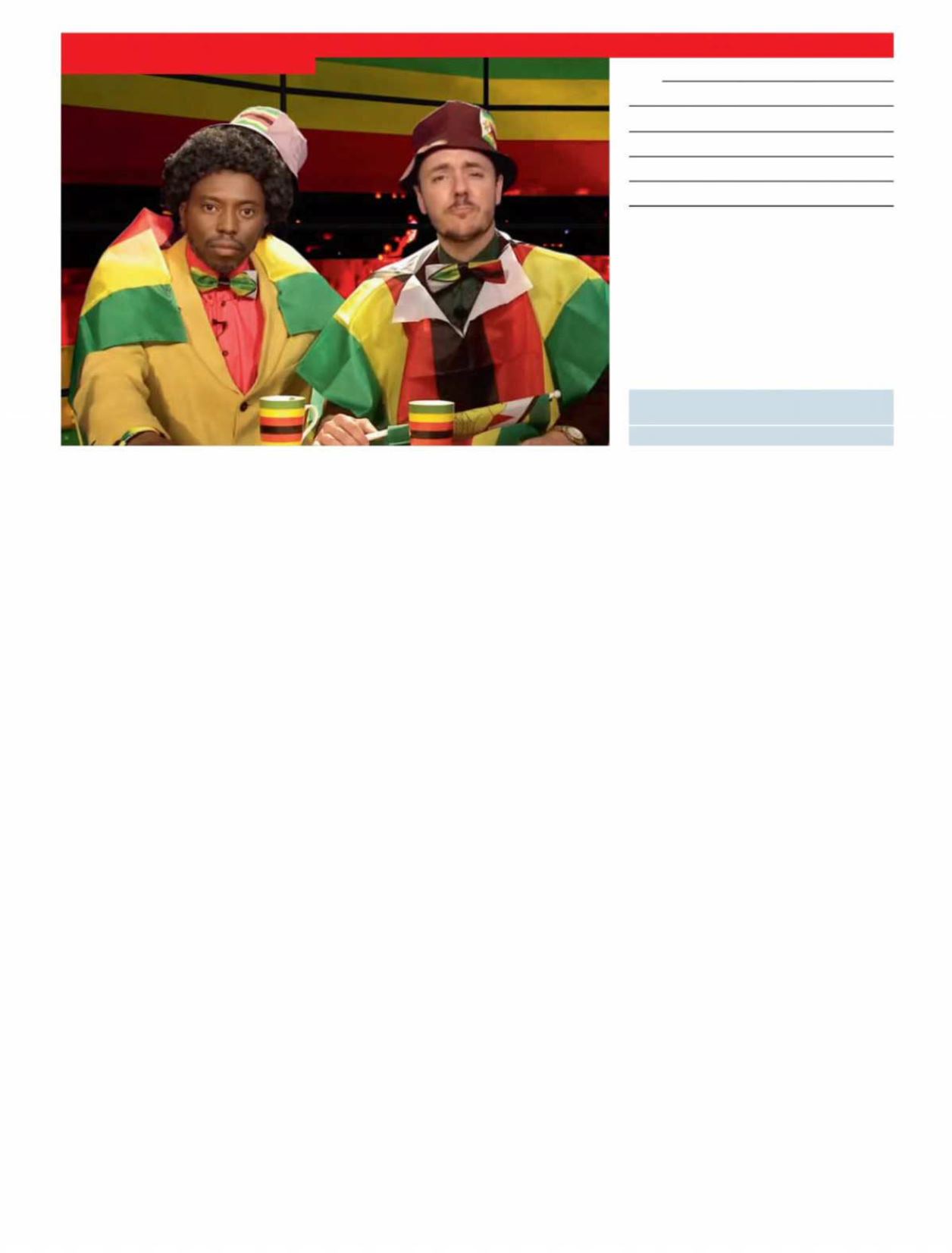

Today, the Magamba Network is franti-

cally putting out jokes ahead of a general

election in JulyorAugust. But it is also in ef-

fect doing reporting, says Samm Monro, a

white Zimbabwean who appears as his al-

ter ego “Comrade Fatso” (pictured right).

The aim is to do for Zimbabwe what the

“Daily Show” or John Oliver do for young

Americans—which, in a country where

most voters are under 40, could be deci-

sive. The gags focus on problems faced by

most Zimbabweans, especially the middle

classes, suchasnot beingable to getmoney

from the banks. As well as the comedy,

which (likeMr Ncube’s stand-up) ismostly

in English, the network’s projects include

live reporting of parliamentary hearings

and social-media initiatives in Shona and

Ndebele, the twomain languages.

Emmerson Mnangagwa, the former

vice-president who tookover fromMrMu-

gabe and is known to Zimbabweans as

“

EDM

” or “the crocodile”, iswidely expect-

ed to win the vote. Charles Munganasa,

the director of “Operation Restore Regasi”,

says he is optimistic about that outcome.

He pours praise on Mr Mnangagwa, argu-

growing industry. Comedians are now

“rock stars in Zimbabwe”, says Mr Ncube.

The boom demonstrates the lightning

speed at which prohibitions can crumble,

and the cathartic benefits that can follow.

But Zimbabwe’s comics are not merely the

beneficiaries of political change. They are

activelyworking to cement it.

You’ve been awonderful audience

With a goatee and square spectacles, Mr

Ncube has a professional mien. His ap-

pearance belies his bravery. Over the past

few years, he has developed an entire rep-

ertoire around his fear of Mr Mugabe. His

trickwas tomake the joke without making

it. Afewyears ago, he even told one in front

of the president himself. “Your excellency,

thank you so much for allowing me to be

here,” he began. “There’s a lot of people

who have been saying things behind your

back, and they’re afraid to say themtoyour

face. I’m not afraid of you. I’m going to say

what everyone else has been saying right

now.” And then, when the tension among

the assembled politicians was at its peak,

the punchline: “Everyone here wants to

know if they can get a selfiewith you?”

For much of the tail-end of Mr Mu-

gabe’s reign, Mr Ncube decided to stay

away from Zimbabwe. “I called it going on

tour, but I was pretty much in exile,” he

says. Satire was dangerous; Mr Ncube says

the government would even blame him

for other people’s tweets. But it took off

Satire in Zimbabwe

The last laugh

HARARE

Zimbabwe’s comedians testify to the changes since RobertMugabe’s fall. Nowthey

want to keep their freedom

Books and arts

Also in this section

76 Johnson: The weasel voice

77 The tragedy of Arnhem

77 Rachel Kushner goes behind bars

78 A tribute to Philip Roth