The Economist

June 9th 2018

Finance and economics 65

A

MERICA’S unemployment statistics at-

tract close attention, even from presi-

dents. Early on June 1st President Donald

Trump tweeted that he was looking for-

ward to the latest figure (3.8%), released

that morning. China’s unemployment

numbers, by contrast, attract mostly ridi-

cule. They have barely budged since 2011

despite the upheavals of the period.

Many China-watchers therefore hoped

that a new measure of unemployment,

dating from 2016 but published monthly

since April, would be more revealing. Un-

like the older statistic, which counts only

those registered as jobless at local labour

offices, the new measure draws on a sur-

veyofthe labour force, collectedby trained

enumerators and beamed directly to Beij-

ing beyond the grasp of local officials. It

now covers 120,000 households across ur-

ban China (on top of a longer-running sur-

vey of 31 cities), providing, in theory, a rep-

resentative snapshot of the biggest

unemployed population in theworld.

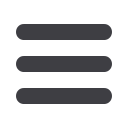

To no one’s surprise, the newnumber is

well belowthe government’s target of5.5%.

And unlike America’s figure, it also seems

boringly stable (see chart). That has led

many to dismiss it as propaganda. But such

a judgmentmaybe toohasty. IfChina’s un-

employment figures do not behave like

America’s, that may be because Asian un-

employment bears little resemblance to its

Western counterpart.

In many developing countries, unem-

ployment is low simply because few peo-

ple can afford it. Jobless benefits are patchy.

In their absence, most people have to eke

out a living to survive. Unemployment is,

in effect, a “luxury good”, notes Ajit Ghose

of India’s Institute for Human Develop-

ment, a research organisation.

Even when they are available, benefits

may not be worth the bother. In Thailand,

for example, payments last sixmonths and

range from 1,650 baht per month ($52) to

15,000. To be eligible, a Thai worker must

register with the social-security office. But

only one in three does so, according to

Warn Lekfuangfu, an economist at Chula-

longkornUniversity. Many remain outside

the formal economy, where they are de-

nied benefits but also spared taxes.

What do they do instead? A laid-off fac-

toryworker might lend a hand on the fam-

ily farm, become a casual day labourer, or

sell trinkets on the street. “There’s a pletho-

ra of low-wage jobs” in the region, points

out Sara Elder of the International Labour

Organisation (

ILO

) in Bangkok. At her hus-

band’s gym, ten people wait to help him

with the climbing wall. In France, he

would have to get bywith only one.

When Annan Chanthan left his job as a

graphic designer in Bangkokfive years ago,

he thought about collecting unemploy-

ment benefits, but never bothered. He now

earns more money selling lottery tickets

next to Hua Lamphong railway station

than he did in his former profession.

In poor countries, unemployment is

paradoxicallyconcentratedamongthebet-

ter offand better educated. They can afford

to wait a bit for a job that matches their as-

pirations and qualifications. Their behav-

iour may also explain unemployment’s

curious stability. “Even relatively well-off

people cannot wait indefinitely,” Mr

Ghose points out. Thus when times are

bad, theymay settle for aworse job or stop

looking, rather than wait longer, which

would add to the rate of unemployment.

Fulsome employment

The peculiarities ofunemployment figures

are not always appreciated by the govern-

ments that publish them. Some policy-

makers even complain that the statistic is

too low. “They hate the unemployment

rate in Africa; they’re very vocal about it,”

Ms Elder says. For many years, Liberia’s

jobless rate was said to be 85%, an outlan-

dish figure that nonetheless symbolised

the country’s genuine economic distress.

When the government carriedout aproper

count in 2010, it discovered that the true

rate, strictly defined, was under 3%.

Some governments nudge the measure

upwards. They count people who are not

immediately available to start work or not

actively seeking it. Indonesia, for example,

includes “discouragedworkers”, whohave

given up looking for a job. Its national

number was 5.4% in 2017, compared with

the

ILO

estimate of 4.2%.

Countries seeking higher rates may

soon get their wish. In 2013 the world’s la-

bour statisticians resolved to change the

definition of the labour force, excluding

people, such as subsistence farmers, who

produce goods for their own family’s use.

That doesnot change thenumberofunem-

ployed. But it does shrink the labour force.

Thus when the new definition is imple-

mented, an unchanged number of unem-

ployed people will constitute a higher per-

centage of a smaller labour force. In a rural

country like Laos, the effect is dramatic. Its

unemployment ratewas 0.7% in 2010 using

the old definition but jumped to 9.6% in

2017, using the new, stricter one.

Ultimately, a lowunemployment rate is

evidence only that people areworking, not

that they are working well. Work may be

poorlypaid, periodic and precarious. In In-

donesia, less than half of those in employ-

ment collect a recognisable wage or salary.

The rest mostly work for themselves or

their families.

Patchy employment is by no means the

preserve of poor countries. It is becoming

more prominent in richer nations also,

notes Mr Ghose. On his last visit to Cam-

bridge University, he learnt that some staff

in the faculty cafeteria did not find out un-

til Friday whether they would be working

the following week. When he was a stu-

dent at Cambridge decades ago, things

were not like that at all, he says. In Britain

and America, the unemployment rate is

nowreminiscent ofthat past age offull em-

ployment. But as Asia demonstrates, full

employment can sometimes be surpris-

ingly threadbare.

7

Joblessness in Asia

The luxury of unemployment

BANGKOK AND HONG KONG

In developing countries, manypeople cannot afford not towork

Measure forced leisure

Sources: Haver Analytics; Huatai Securities;

China’s National Bureau of Statistics;

The Economist

Unemployment rate, %

2014

15

16

17 18

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Taiwan

Malaysia

Thailand

China (31 big cities)

China

(new series)

No time for tweeting