The Economist

June 9th 2018

Asia 23

1

2

tees that the Kim regime will be safe from

American attack if it agrees to disarm.

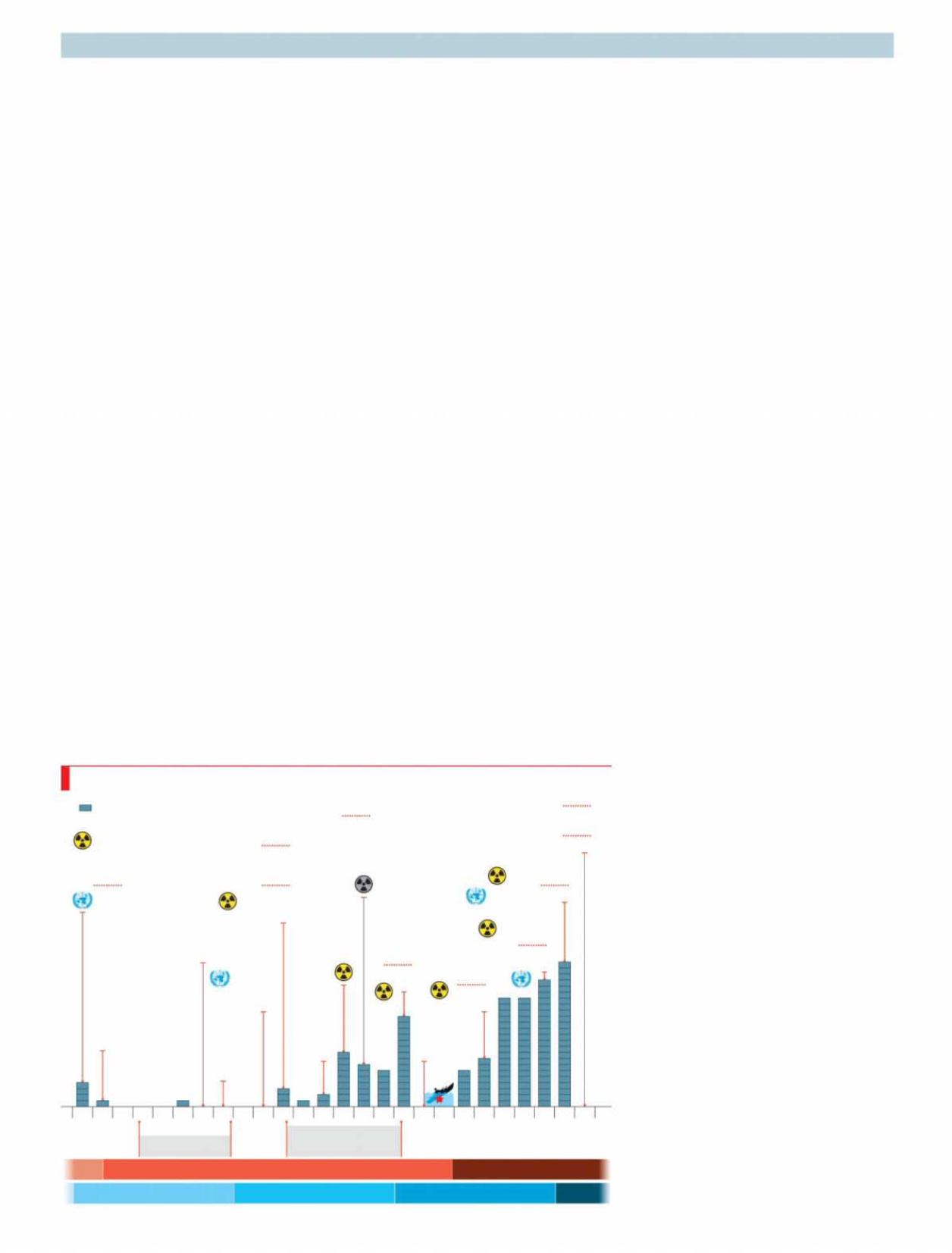

The problem is that all this has been

tried before. The two Koreas first forswore

nuclear weapons in a solemn agreement

in 1992, shortly after America removed tac-

tical nuclear weapons from its bases in

South Korea. But in 1994 the ageing “Great

Leader”, Kim Il Sung, kicked out interna-

tional inspectors and threatened to divert

plutonium from a nuclear reactor into half

a dozen primitive bombs. Under an

“Agreed Framework” in late 1994 the North

promised to abandon illicit work on pluto-

niumweapons, in return forAmerican aid,

oil and civilian nuclear reactors. In1999 the

North was bribed with sanctions relief to

give up missile testing, and in 2000 a sum-

mit between leaders of the two Koreas

prompted talk of a visit by President Bill

Clinton (in the end, he only made the trip

after leaving office). By 2002 North Korea

revealed it had a secret uranium weapons

programme and expelled international in-

spectors, leading to a multilateral peace

drive called the “six-party talks”. Those

lasted until a nuclear test in 2006. The

North tested five further nuclear devices

between 2009 and 2017. North Korea also

defied the

UN

Security Council to test bal-

listic missiles of increasing range, culmi-

nating last year in several tests of devices

capable of hitting the Americanmainland.

Christopher Hill, a former American

diplomat, recalls stirring language about

working towards a “permanent peace re-

gime on the Korean Peninsula” in an agree-

ment signed by America, China, Japan,

North Korea, Russia and South Korea in

2005, as part of the six-party talks. That

agreement also included North Korean

promises to give up nuclearweapons, sub-

mit to international inspections, and rejoin

the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (

NPT

)

fromwhich it had earlier stalked.

Back then, America offered explicit se-

curity guarantees that it had no intention

to attackor invade North Koreawith either

nuclear or conventional weapons and

guaranteed that it had no nuclearweapons

deployed in South Korea. Even the idea of

exchanging interests sections has been

tried, at China’s urging, Mr Hill recalls. He

worked mightily to convince a sceptical

Bush administration to agree to the idea,

then took it to the North in 2007. “They re-

jected it on the spot,” the former ambassa-

dor sighs. “TheNorthKoreans tend towant

something until they don’t want it.”

Justmaybe

There are reasons to imagine, however,

that theNorthmaybemore eager for a deal

this time than it has been in the past.

Thoughnuclearweapons remain the pillar

of Mr Kim’s regime and are popular with

ordinary North Koreans, the elites have

also become attached to the minor eco-

nomic boom over which Mr Kim has pre-

sided, says Andrei Lankov of Kookmin

University in Seoul. Mr Kim has even

promised to embrace growth aswell as de-

fence, after years of putting weapons-

building first.

Mr Kim has gone further than his fore-

bears in giving priority to economic devel-

opment, tolerating a big, semi-legal “grey

market” and allowing the running of de

facto private enterprises within state-

owned firms. He has even encouraged

private investment by his subjects. One

government regulation calls for the “utili-

sation and mobilisation of the unused

funds ofresidents”. SinceMrKimtookover

in 2011, the economy has grown in the low

single digits every year bar one, according

to statistics compiled by South Korea’s cen-

tral bank. Although those numbers are un-

reliable, they mark a striking departure

from the economic collapse and wide-

spread famine over which Mr Kim’s father

presided. North Korean officials have told

foreign visitors that Mr Kim hopes to emu-

late Vietnam, which has grown rapidly

after making peace with America, in part

to hedge against a risingChina.

At a minimum, Mr Kim will be keen to

secure some easing of sanctions. Imports

of solar panels from China, which had

been rising rapidly until last year as well-

to-do residents of Pyongyang tried to be-

come independent of the unreliable pow-

er supply, fell to zero in March for the first

time in eight years, according to Chinese

customs statistics analysed by

NK

News.

Fuel prices spiked in earlyApril, and

NGO

s

have begun to notice shortages of fertiliser

in the countryside. None of this will have

improved the mood of North Korea’s

quasi-capitalists. “These people like mak-

ingmoney, and if they stopmakingmoney

or suffer discomfort, that will be a problem

for the leadership,” saysMr Lankov.

What ismore, Mr Kimmay see a chance

of a breakthrough. North Korea has made

great efforts to understand American poli-

tics in the Trump era. North Korean offi-

cials have been asking foreign contacts

about such arcana as the implications of

the recent Republican loss of a Senate seat

in Alabama. According to the Chinese aca-

demic, the regime has decided that Mr

Trump has no firm ideology and is a deal-

maker unlike any president they have en-

countered. Against that, his recent pull-out

of the Iran nuclear deal makes him look

like a deal-breaker. On balance, he says, Mr

Kim’s side senses opportunitiesworth test-

ing. The current rivalry between America

and China provides another opportunity,

to play themoffagainst each other.

Mr Trump, meanwhile, seems deter-

mined to be emollient. Despite declaring

in lateMay that he was calling off the sum-

mit because of the North’s “open hostil-

ity”, Mr Trumpwarmly received one ofMr

Kim’s henchmen at theWhiteHouse, bear-

ing an absurdly large letter from his boss.

Soon afterwards, Mr Trump reinstated the

meeting, despite the lack of any clear pub-

lic commitments from the North on disar-

mament, for example. (The contents of the

giant letter have not been disclosed.) John

Bolton, Mr Trump’s national security ad-

viser, has been kept in the background,

after he infuriated the North by citing Lib-

ya’s complete dismantling of its nuclear

programme as a model, even though the

Libyan leader who agreed to this, Muam-

marQaddafi, ended up dead in a ditch.

Most importantly, Mr Trump seems to

North Korea’s nuclear path

Kim Jong Il

Kim Jong Un

George W. Bush

Barack Obama

NK supreme

leaders

and

US presidents

Donald

Trump

Bill Clinton

Kim Il

Sung

1993 94 95 96 97 98 99 2000 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

Threatens to

leave Nuclear

Non-Proliferation

Treaty (NPT),

then relents

UN inspectors say

North Korea is

hiding evidence of

nuclear fuel for

bombmaking

Agrees to

freeze testing

on long-

range missiles

First summit

between

North and

South since

end of

Korean War

Signs “agreed framework”

with US to freeze and

dismantle nuclear

programme in exchange

for nuclear reactors,

aid and easing of

sanctions

Carries out 1st

underground

nuclear test

3rd nuclear test

Restarts

nuclear reactor

4th and 5th

nuclear tests

6th nuclear test

Planned summit with Mr Trump in Singapore

Partially demolishes

underground nuclear test site

Two summits between leaders of North

and South in demilitarised zone

Further UN sanctions

UN agrees on

new sanctions

Agrees to

return to

NPT. One

day later,

demands

reactor

from US

Expels UN

inspectors;

pulls out of

talks and

restarts

nuclear

facilities

2nd nuclear

test

Sinks

South

Korean

warship

Six-party talks with

China, Russia, US, Japan

and South Korea

Series of US-North

Korean talks

Expels UN

inspectors

from nuclear

facilities

Withdraws from NPT

Declares

reactivation of

nuclear facilities

Says it will disable

nuclear facilities.

US agrees to

unfreeze assets

and provide aid

Second summit

with South Korea

Announces it

has nuclear

weapons

Sources: CSIS;

The Economist

Missile tests